Atomic Archetypes

Peace Signs and Other Depictions of War

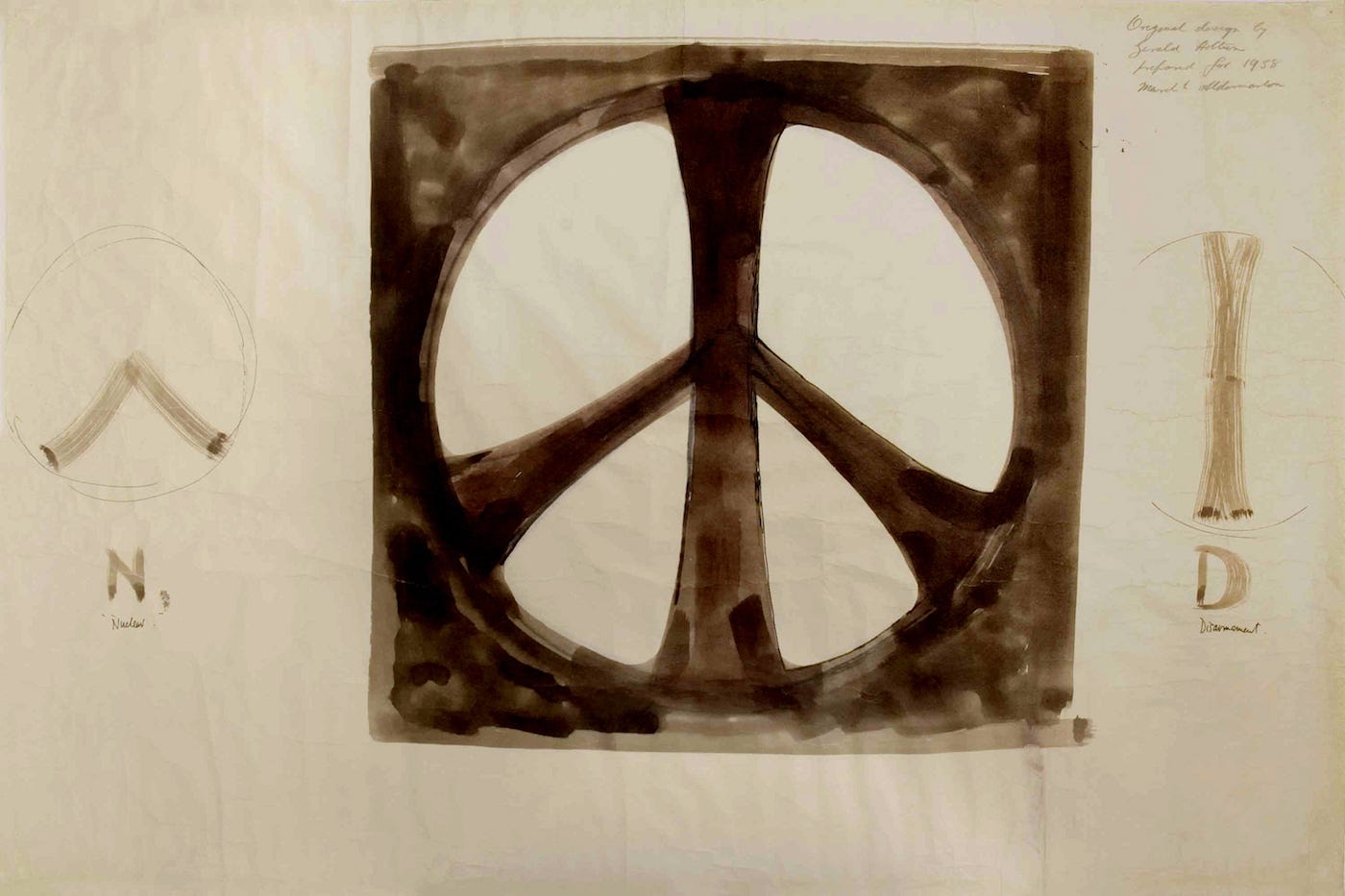

In 1958, British artist and designer Gerald Holtom put pen to paper and began to draw a self-portrait. “I was in despair,” he said of this artistic discovery: “Deep despair. I drew myself: the representative of an individual in despair, with hands palm outstretched outward and downward in the manner of Goya's peasant before the firing squad. I formalized the drawing into a line and put a circle round it. It was ridiculous at first and such a puny thing.”

Holtom refers to an 1814 painting by Francisco Goya, titled ‘The Third of May 1808,’ depicting the execution of Spanish hostages by Napoleon’s armies during the Peninsular War. As many have noticed, it seems that Holtom misremembered the painting, in which Goya’s hostage raises his hands to the night sky, visible stigmata on his palms—an emblem of divine suffering and Vitruvian everyman on bended knee. His executioners, hunched and advancing, have turned their backs to our perspective, insofar as the viewer occupies a plausible, rather than moral, stance.

In his writing on Goya’s portraiture, critic T.J. Clark describes how Goya draws attention to the ideological dimension of each portrait by various de-realisations of a sitter’s scenery. Likewise, the distorted perspective of this painting produces a starkly interpersonal confrontation between hostage and executioner. In this collapsing of perspective, Goya preserves two asymmetrical fronts at a distance of mere feet—a would-be humanizing proximity that instead presents a space of hollow horror.

The painting occupies a preeminent place in the development of modern art technique and its supportive consciousness—of history, scenery, self. Nonetheless, the interfacial paradigm of war that Goya focuses, from the side of the victim of course, belongs to premodern experience—which is only to say that it belongs to the realm of experience in general. As the means of modern warfare tend to ever-greater efficiency and its theatre swells to encompass the very air between us, Goya’s visualization has withstood many amendments in the interceding centuries.

Soonest, perhaps, Édouard Manet’s 1867 series, ‘The Execution of Emperor Maximilian,’ depicts the abrupt dispatch of Maximilian I, puppet Emperor of the French-backed Mexican Empire, alongside generals Mejía and Miramón at the hands of a Republican militia that same year. Manet painted this scene several times with shifting affinities; but in the most evocative instalments of this series, Maximilian’s figure is enveloped by gun smoke, as if a living canvas had been smudged.

While Goya’s view upon an execution omits any possibility of identification with the riflemen of an invading army, Manet seems to distribute sympathy from canvas to canvas. At the right of each attempt, however, a doleful sergeant faces the painter directly, examining his rifle as if to decline his task. This humanistic solicitude for the gunmen and the difficulty of their task indicates support for the nationalist cause; but as importantly, Manet’s envisioning belongs, alongside Goya’s claustrophobic didactic, to an interfacial order; apt to painting in both scale and scenery.

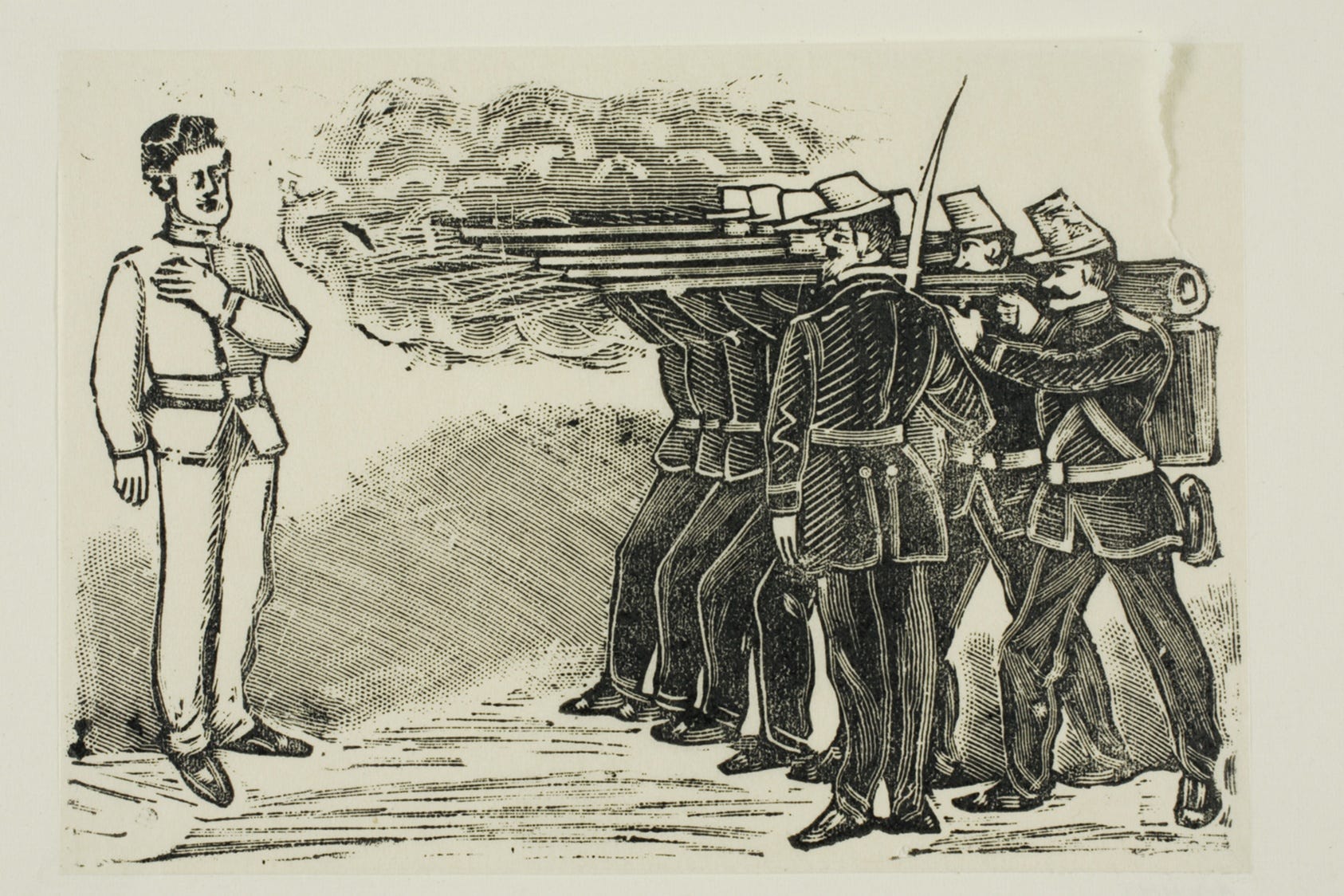

Political cartoonist and lithographer José Guadalupe Posada echoes the duplexity of this micro-genre more starkly throughout his works, as befits his medium of choice as well as the frequency of political executions leading up to the Mexican Revolution. Broadsides depict the execution of Zapatistas from over the shoulders of onlookers and infantry, as a kind of proto-photographic proof of death; elsewhere, the exploits of romantic criminals such as Jesus Bruno Martinez are serialized unto a climatic public ritual. In an engraving below, the sentenced man appears poised and alive in the instant of his death, even levitating above the earth.

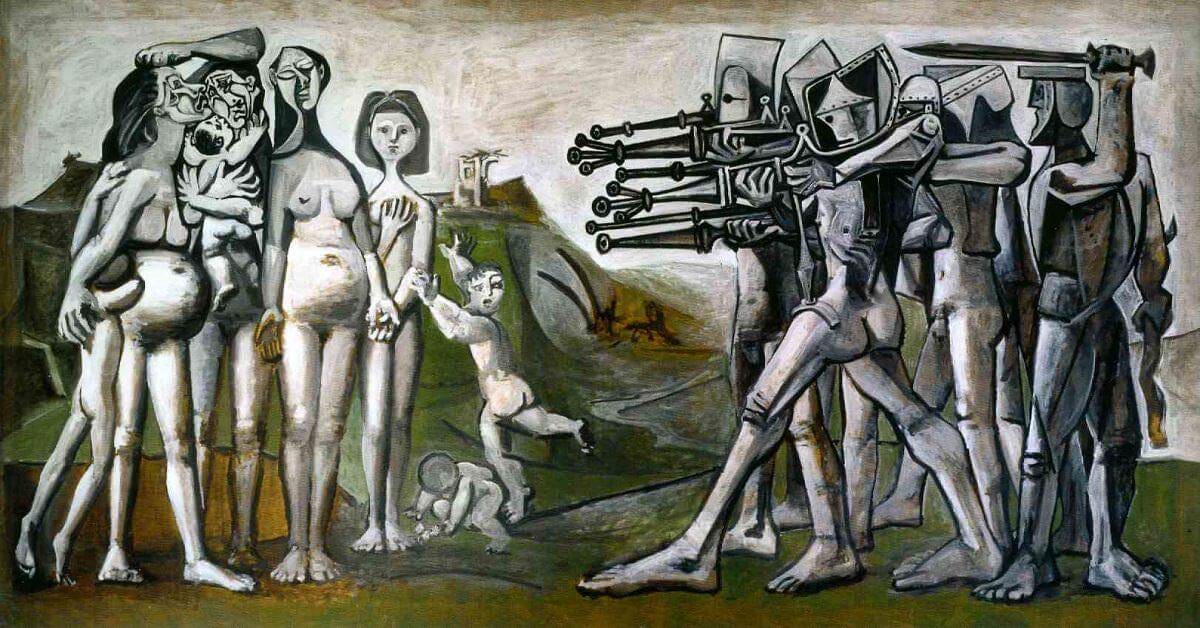

Most famously, Pablo Picasso’s 1951 painting ‘Massacre in Korea’ depicts an American firing squad during the Korean War, whose surreally anachronistic weapons are turned upon a rival troop of absolutely vulnerable women and children. The cascading hills and distant structures recall Goya’s Spanish landscape, conveying Sinch'ŏn to Madrid—but in 1951, Picasso draws upon an archaic visual arsenal, evoking a bygone age of chivalry, however bloody. Facial disfigurements and occlusions allude to the chance of recognition—as notably, the soldiers and the families they would massacre stand on the same expanse of earth with bare feet.

Picasso’s symmetric yet unmatched standoff continues the Goyaesque trajectory, after developments in war and art had rendered such visions of military intimacy largely irrelevant. By mid-century, photography supplants the project of historical and moral observation. As importantly, artistic developments tail the intensification of war, from the harrowed portraiture of German expressionism to the severe geometries and motion lines of British and Italian avant-gardes. Artworks of technical mimesis begin to edge out artworks of fidelitous witness; and as a response to further escalation trends, a secular reinvestment in allegory and symbolism will characterize many of the most significant responses to the Second World War. In popular genealogies of art, Picasso himself stands in for many of these developments, which condition the didactic, communist phase of painting during which he produced ‘Massacre in Korea.’

In the scenes above, both Goya and Picasso depict war as a stick-up, transpiring at bayonet-length between legible participants. This isn’t quaint—rather, in contrast to Manet’s solicitude or Posada’s visual headlines, these painterly depictions of the senselessness of war are best conceived as something other then acts of historical witness or commemoration. Rather, the continuum of Goya’s influence consists in so many dichotomous emblems of the clash between those who want to live and those who would kill—visual abstractions of the moral stakes of war, no matter the complexity or geopolitical pretence.

That said, by the time of Picasso’s reply, war had been renovated at least several times in the twentieth-century alone. Firstly, by the trenches of the first World War, a tellurian accompaniment to increasingly heavy artillery. Secondly and more saliently, by the deployment of chemical weapons such as chlorine gas, introducing what philosopher Peter Sloterdijk describes as an “atmo-terrorist” paradigm, intended to decrease the liveability of an enemy’s immediate environs, actually conscripting a human target’s biological functions in the cause of their own death. (Needless to say, this horrific innovation only awaits its genocidal deployment in Nazi-run concentration camps during the Second World War.) Thirdly, by the events of August 6th, 1945, on which day the United States dropped the atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima, Japan; followed by the bombing of Nagasaki on August 9th. This third moment of warfare follows its precedents in the precise sense of a dialectical apex: hereafter, the horror of increasingly remote warfare augured by aerial bombardments compounds the climatological corruption, and disruption, of a targeted population’s life systems initiated by the research and development of state terrorists during the world wars. Further instalments are only implied by the numeralization; war will never be so regional again.

Holtom’s 1958 portrait proceeds directly from these developments—commissioned by the Direct Action Committee against Nuclear War (DAC) for use in an Easter march from England’s Atomic Weapons Research Establishment in Aldermaston to the capital of London. This march would become an annual attraction, drawing together hundreds of thousands of participants from all sections of civil society—political organizations, faith groups, students, workers, and more. DAC would soon merge the recently convened Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), whose tactics were more varied and acceptable to popular opinion; and their coalition would take Holtom’s artwork as its logo, soon to travel the world.

Holtom’s own account of his creation is frequently quoted, but rarely is his own comparison followed to its most difficult conclusions. Where his citation of ‘May 1808’ proposes that we read his portrait through Goya’s polarized staging, its solitary figure places us on the side of the executioner implicitly—as if the circle is a rifle scope. This one-sided depiction of the stakes of war, previously understood as a collective trauma that necessarily transpires in the interhuman sphere, not only inculpates us in the very act of witness, but refuses visualization as such.

As a glyphic reduction of a grislier scene, Holtom’s token has an obvious religious precedent; much as Goya’s visions of war, to bear further, borrow from lushly instructive visualizations of Christ’s suffering, which are reduced in the bare cross or crucifix. Like the Christian cross, which emblematizes all of the suffering of the world displaced onto a single body, Holtom’s absolute individual in the scope of fire is reductio ad hominem of collective disaster. The existential crux of Holtom’s design takes on a universal signification by way of the enlarged stakes of nuclear cataclysm—an absolute death that obliterates the basis for personal remembrance and cultural posterity, socializing the private dilemma of being-toward-death. Beyond Christian soteriology, one no longer dies for humanity; humanity dies as one.

That said, Holtom’s self-portrait was never intended as a simple emblem of monadic enclosure or unactionable despair. To the degree that its runic abstraction is figural, its subject stands socially encircled; even drawing power from the border. In an original draft, the quasi-Druidic central figure appears a tree with roots; an altered cross with arms outstretched. And while Holtom’s design harmonizes the enclosed ‘A’ that stands for Anarchy in the popular imagination, its alphabetic content is differently encoded. To the left and right of his original sketch, Holtom includes the semaphore signals for the letters ‘N’ and ‘D,’ or Nuclear Disarmament.

This well-concealed initialism, coinciding with the portrait of an abstract supplicant, becomes one of the most indelible symbols of a decade and a century. Known throughout the world as “the peace sign,” the logo of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament adorns tie-dye and banner, punk anthology and pottery, bumper sticker and boutique apparel—the list is actually endless. The online classified website Craigslist uses the CND logo as a favourite icon, and even tried to register it as their own: in response to which the United States Patent and Trademark Office ruled that the artwork in question was a "pervasive universally-recognized symbol (and has been for over fifty years) that would not be perceived as belonging to any one party.”

This ruling, unfortunately, also describes CND’s claim upon the image, long since obscured in circulation. CND continues to organize today against the backdrop of an escalating intercontinental Cold War and a renewed arms race between nuclear powers, but the peace sign has been absorbed into a merely aesthetic understanding of the nineteen-sixties, foreclosing any present-day peace movement as a quaint holdover from an era of undifferentiated love and quiescence. What we see in the original architecture of Holtom’s design, however, is a far more sober realization.

Holtom evokes ‘The Third of May 1808’ by way of artistic license, but his existential emblem more closely resembles the first of Goya’s ‘Depictions of War,’ titled ‘Tristes presentimientos de lo que ha de acontecer,’ or “sad presentiments of what must come to pass.” In this etching, from which unfurls a gallery of atrocities, Goya’s lone supplicant looks skyward, enshrouded by dark, shirt torn and palms outstretched. Not only are his arms faced downward as in Holtom’s false recollection of the larger painting; the central figure is enframed by densely cross-hatched shadows, behind which one perceives shapely curlicues of spirits on the air, marauding factions of the night. Goya’s etchings are not only vivid social commentary, nor postural studies of mortal endurance—variously vivisected, these subjects correspond to the bodily abstractions of war-as-torture; a realist view on anti- or re-figural violences.

Notably, this posthumous folio anticipates both photographic and allegorical turns in the artistic witness of war. Prior to the nuclear era, the nature of war permitted its miniaturization as a scenic space of dyadic encounter. For more than a century, this has been less and less the case. The art of the First World War tends to the depiction of one’s own ranks along increasingly desolate fronts, as the spaces and senses of military confrontation were rapidly reconfigured; and much art of the Second tends to the depiction of aftermath—an historically symptomatic genre of delayed witness and horrified retrospection, evacuated of reason or wisdom.

By contrast, the art of the nuclear era tends to impure abstraction, such as one sees in post-Futurist Italian movements like Eaismo and Il Movimento Arte Nucleare, whose thematization of the bomb assigns both a terrible cause and content to abstract painting at mid-century. Eerily enough, these movements were not altogether condemnatory of the age for which they are named—the advanced humanism of Eaismo, outlined in Voltolino Fontani’s manifesto of 1948, proceeds from the “atomic disintegration” of a century with gleeful technophilia; where Il Movimento Arte Nucleare sought “an atomic superfuel for interplanetary flight” in the wake of unprecedented catastrophe. Nonetheless, the visions of these artists powerfully counterpose the pacificatory, rather than pacifist, designs of US-backed abstraction at the height of the nuclear arms race.

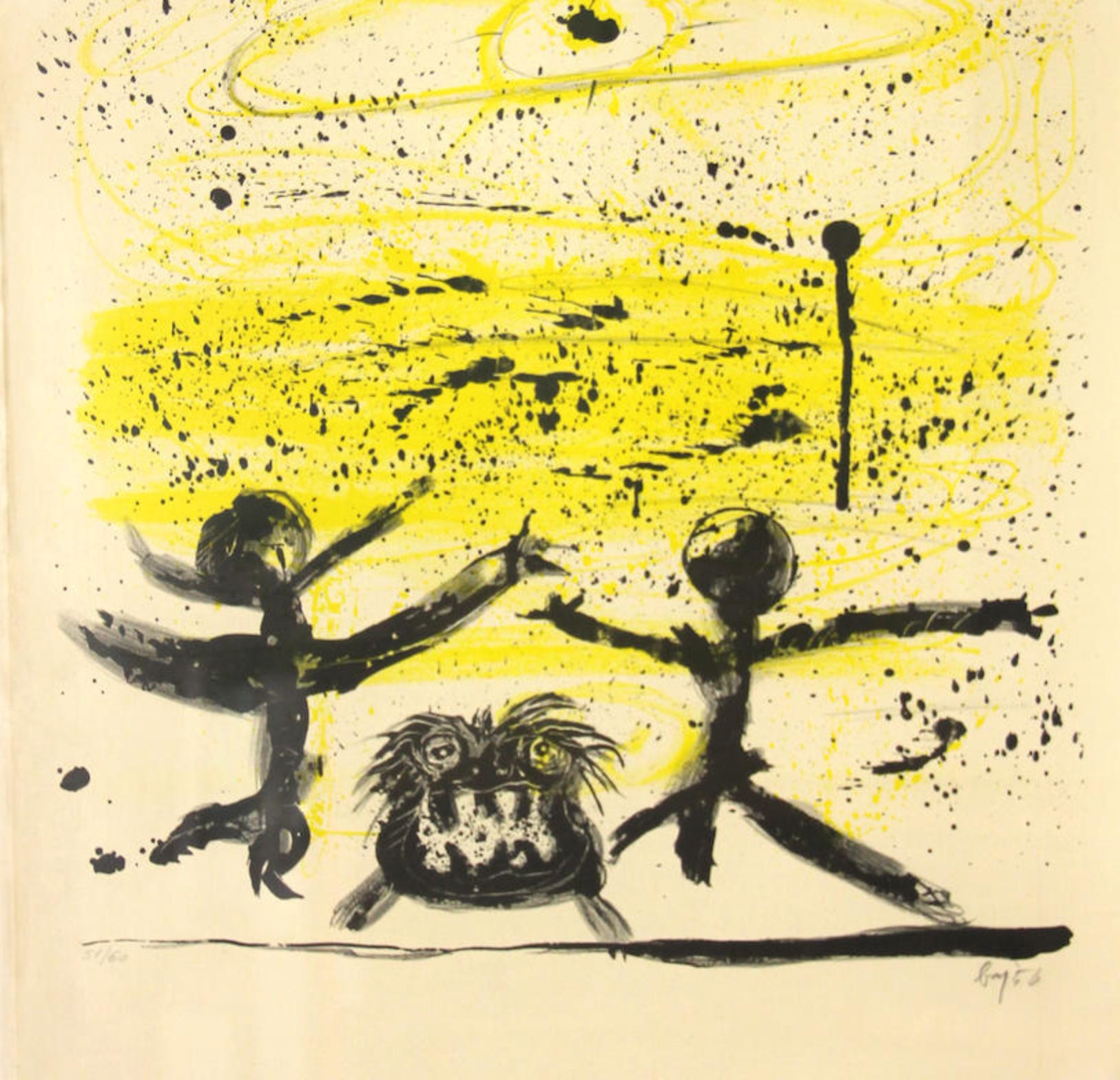

Enrico Baj’s painting ‘Due bambini nella notte nucleare’ (‘Two Children in Nuclear Night’) mediates the moral-figural mode with a contemporary drive to abstraction, where the latter value is operated by the bomb itself. The children in question appear as shadows against a fiery background, stick-like arms outstretched; spherical heads placed atop boxy torsos as if by a child’s own hand. With no more distinguishing features than human directionals, these doll-like outlines nonetheless implore survival from their place in a molten landscape. Top left, a blotchy torus, perhaps a distant explosion or eclipse, extends the illusion of depth as it mirrors the orb-like immolants in the foreground. Baj was a proud exponent of action painting, and his kinetic technique, dripping and smearing oils across a crimson sky, places debris on the virtual air, evoking absolute atmospheric corruption.

The affinity of ‘Due bambini nella notte nucleare’ with Goya’s depiction of war and its subsequent echoes is apparent at a glance. In Baj’s painting, two figures face the viewer from the centre of a simple landscape, standing athwart one another on supportive, scorching, earth. Their assassin appears nowhere within this impossible framing, however, in which the children—“hands palm outstretched outward and downward”—die irremediably alone.

In a lighter piece from the same year, 'Il cielo era giallo,' Baj depicts two splayed, flailing figures beneath a radiant eye. The title possibly refers to contemporary descriptions of Hiroshima after the attacks—poet and survivor Sankichi Tōge writes of a “swirling yellow smoke” on the air—and once more, the artist’s nervous motion drafts an elemental turbidity, flocks of flecks descending on stick figures below. The pair’s featurelessness contrasts the endearing maw of an unidentifiable pet, either a pitiable victim or an allegorical element, fiero monstruo of the nameless maelstrom. As powerfully, Baj’s humanoids, cruciform in the instant of their destruction, harmonize the Goyan figure hidden at the heart of Holtom’s atomic pendant.

Implausible as it may seem, perhaps this archetypal solidarity extends from the severe reductions of the bomb itself—of life to principle, of individual to numeral, of cities to their scaffold, and of history to suffering. As we inherit Holtom’s cause today against our will, encircled by so many of the same conditions, perhaps we can also look afresh at his ubiquitous emblem of disarmament—not as a visual platitude but as a portrait of the age, placed after a tradition that depicts war as a sad presentiment of peace.