Carnival Against the Nazis

On RAR, AYM, ANL, and etc

There are many lessons to be drawn from the rash of racist violence presently washing across the UK, and more from longer waves of anti-fascist resistance. As Starmer-era Labour rhetoric on immigration continues to merge that of not just Tories but the further right, we should be clear on the extent to which mainstream Islamophobia, and Labour's securitized immigration policy, have prepared the unacceptable. Tommy Robinson's English Defense League may have re-soled their boots for this occasion, but the bigots in Parliament have given them traction. And as we watch working people turn on their neighbours, and thousands more join in a stand against this latent hate, we must base our anti-racist movements on the impossibility of neutrality in fascisizing times.

Just as the present confrontation follows from a long history of fascist creep in the UK, there's ample precedent for resistance. In a careful rumination on these previous successes and the current situation, activist David Rosenberg cautions that "the past is not always our guide." For starters, Rosenberg names some features of the new far-right; including its consilience with the policies of neoliberalism, and its physical citation of an insurrectionary means that tends to fragmentation and dispersal.

As noted, this new right is incited by both Labour and Tories, where all parties agree on a closed and foreboding approach to immigration, making differently styled appeals to a consolidated Englishness. This tacit instruction to violence cannot be underrated in the diagnosis of Europe's political culture. But as Rosenberg notes, the lack of top-down strategy from the fascists themselves gives these outbursts a different character. Parties like the National Front or BNP are not at the centre of this movement, and neo-Nazi groups like Patriotic Alternative are meddling rather than leading, partaking of a momentum that is baser and more mainstream at once. This acknowledgement needn’t downplay the role of organized cells within the present riots, but the dialectic of organization and spontaneity, no less germane to right-wing rallying than leftist strategy, is decided for spontaneity at this moment.

This apparent disorganization isn't consoling. If anything, the official political weakness of the far-right indicates that this fascist surge was prepared elsewhere; in the unconscious of a nation, by the available terms of liberal, and illiberal, discourse. The potentially electable Reform UK is bound to benefit from the fact that both Labour and Tories already launder its racist ideas in Parliament, and we've seen their rhetoric take to the streets.

So what's next? The first priority must be to overwhelm the right, by all means and on every front; and for inspiration, anti-racist activists recall the raucous ferment of the 1970s and 80s, when groups like the Anti-Nazi League (ANL) worked in the massively popular Rock Against Racism movement. "Some older anti-fascists have posted images of their Rock Against Racism (RAR) badges," Rosenberg writes, "recalling an incredibly exciting and overlapping cultural movement." But the romantic feelings we have for this era and its symbols should be tempered, he reminds us, by all that has transpired since the time of RAR, whose first priority was to create spaces of multicultural encounter:

RAR’s regular gigs in smaller venues around Britain mainly combined punk (almost entirely white) and reggae (almost entirely black). They brought the growing audiences of both genres together at the same gigs. While I enjoy seeing ANL and RAR badges on social media, I hesitated about putting mine up there in response to the riots, because I worry that too simplistic a parallel is being made with the late 1970s. There are important differences, and we can’t simply transplant the main tactics we used in the 1970s.

Rosenberg speaks truly, where the tactics of the ANL presume a certain quality of coalition that has been profoundly weakened throughout the neoliberal era. Its successor groups and parent organizations have split and split again, making the premise of a truly popular front a distant eventuality, pending repair of its militant fractions. And to Rosenberg's primary point, where the ANL was a principally white accompaniment to the daily resistance of migrant communities, such an organization would not be given pride of leadership today in any coalition.

The Love Music Hate Racism campaign has been trying to resuscitate the spirit of the RAR movement and its rallies, or "carnivals," since 2002. In the organization's own words, "Love Music Hate Racism uses the energy and vibrancy of the music scene to promote unity and celebrate diversity through education and events. Our message is simple, there is more that unites us than divides us; and nothing demonstrates this more than music." Bluntly, however, this is no part of a popular front but a festival, and its liberal inclusionist mandate has no organic connection to popular movements, nor to working class organizations, nor to the socialist internationalism that furnished RAR its further horizon.

Even at a distance, it’s hard not to romanticize this past cultural work. Like many readers, I politicized around punk music; and RAR names a moment in which punk mores of a progressive stripe were at the heart and forefront of a mass movement; not as popular concession but as one part of a common front.

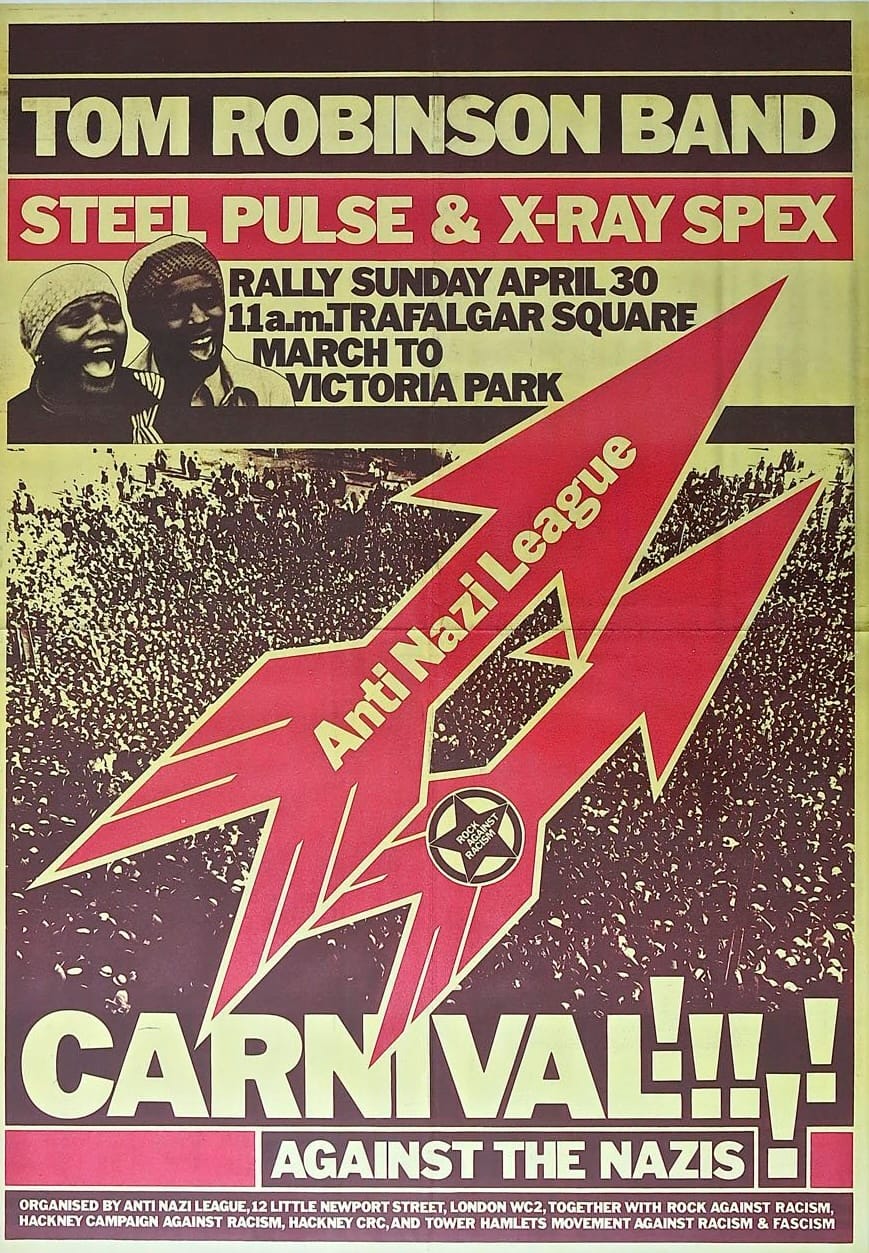

Founded in 1976, the first RAR gig was held at the Princess Alice Pub in London, featuring reggae band Matumbi and singer Carol Grimes. Within a year, there were more than 200 chapters across the UK, and the movement had swelled of necessity to truly mass appeal. Rosenberg recalls two enormous carnivals in London, held in 1978, and another in Manchester, with hundreds of thousands of attendees:

Leading black bands and white bands pushed defiant anti-racist, anti-fascist messages on stage, and celebrated multiculturalism. In the first Carnival in Victoria Park, east London, the Birmingham-based reggae band Steel Pulse donned white hoods for their song Ku Klux Klan, The Clash played an immensely powerful set, and Tom (not Tommy!) Robinson had the whole 80,000 crowd singing the refrain of “Glad to be Gay” — a song that BBC radio had banned.

Steel Pulse were a fixture of the RAR scene, and singer David Hinds was likely its most informed personality, memorializing Soledad Brother George Jackson and anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko in honeyed, unharried anthems. Steel Pulse were enmeshed within punk too, gigging in the tight ecology of London's underground venues. In a recent interview, Hinds recalls the gradual consolidation of the strong reggae-punk axis in the 1970s UK:

Initially a lot of reggae bands didn't see themselves related to it. The general consensus was that it was white people’s music, noisy and non-melodic, with lyrical content that had nothing to do with our energy. Plus we were too busy trying to find our culture, going back to Africa, to hell with you guys, that kind of thing. But then we had our management saying, listen, this is the way to go .. Over time, it became cool to be hanging out with the punk rockers. You started to understand why they behave the way they behave and that it's all about anarchy - they've seen the system for what it was and anything that the system disapproved of, they were into. The punks just made their mind up that anything the establishment was going to say yay or nay to, they'd do the exact opposite. So we said, after all, gosh, I kind of like that! It's a bit like us, really, but from a white man's perspective.

In this remark, Hinds speaks perceptively to the underrated internationalism of early punk, perceiving its often puerile negativity as one moment of a more constructive motion, and recuperating its anti-sociality as a response to a different kind of exclusion. This energetic accord was on full display in the RAR milieu, where Black and white unity was not a goal in itself but a means of getting somewhere together.

One could as soon approach this compact from its other side. At Victoria Park, the Clash chose to close out their set with a furious rendition of 'White Riot,' featuring a tuneless Jimmy Pursey of Sham 69 on its first verse. Issued one year prior as their debut single, the song was inspired by Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon’s attendance of the Notting Hill Carnival in 1976, where over 3000 police brutalized far more Caribbean youth, and were themselves assailed by rioters after attempting to arrest a pickpocket. More than 100 officers were hospitalized, and a high-contrast photo of the melee adorns the sleeve of the group's self-titled LP.

But the inspiration that the Clash took from their experience of Notting Hill was still constrained by a dichotomous racial imaginary, belied by the reality of a far more complex UK. Rather than await a riot of their own, the Clash’s white constituency had to sync up with the mass movements of an Asian and Caribbean working class; and the group's well-intentioned anthem could be said to have awaited its proper reception in the ferment of RAR, in order to be disambiguated from the coy racism of their peers. At an eighty-thousand strong rally against the far-right, however, the one-sided angst of Strummer's lyric is sublated by the crowd, and the chorus sounds an anti-fascist klaxon.

Socialist activist David Widgery described the band as "atrocious poseurs" in his review of the event, though "still brilliant and very radical musicians." It's a quick and funny assessment, counterposed to the more emblematic presence of X-Ray Spex vocalist Poly Styrene, a "Brixton-born, Anglo-African, Shirley Bassey-meets Johnny Rotten-and-wins, punk chantreuse." Most demonstratively, Widgery says, the gig concluded with a jam by members of Steel Pulse, Sham 69, the Clash, and others; an ad hoc collective founded on the rhythms of the West Indies, where "Black struggle is fiercest and the music most intense." Widgery's review paints a picture from the frontlines, of "a positive, joyous carnival against the No Fun, No Future philosophy of the NF," with special attention to the multicultural composition of the program:

The punk-gay-reggae line up was amazing but is real because it expresses the common experience and defiance of inner city life; street heat, maximum unemployment, sexual ambiguities, fuck-all future, corrugated iron and the NF biding their time.

This optimism in the face of menace is largely lacking from our movements today, and with it the perception that the right is bound to lose. Rosenberg's cautionary remark as to the naive duplication of RAR-era tactics is well-taken; but sadly, I don't even perceive us as having the infrastructure or connections to attempt such a cultural front today, placing aside the risk of lapsing into empty repetition. Punk has been parochialized since the heyday of RAR, and while the Free Palestine movement has begun to elicit some naively anti-imperialist rhetoric from a mostly disinterested scene, we still have a long way to go.

Quite separately, Rosenberg's caution against the simplistic adaptation of an ANL playbook isn't only owing to a lack of preparedness, but to real progress in the social movements too. As Rosenberg laments, “the minorities most under direct physical attack—Asian and Caribbean—were relatively absent from the leadership of these movements," which were dominated by white activists from the Socialist Workers Party and other formations. It would be nearly impossible to duplicate this problem of composition today, where movements for racial justice have significantly transformed the terms of capitalism's segregative society—a partial victory that the far-right is determined to claw back.

Rosenberg offers an important corrective to our well-meaning envy of the past; but we could push back a little too, where whitewashing is as often a post hoc, narrative effect upon a movement's membership. Certainly the ANL courted high-profile figures of white British culture for its founding statement, and it was itself a majority white organization. But in key street-level struggles throughout the 1970s, it was only one participant factor in a broad coalition of trade unionists and migrant groups, and we shouldn’t underestimate the contributions of Asian and Caribbean organizations in the era under examination either.

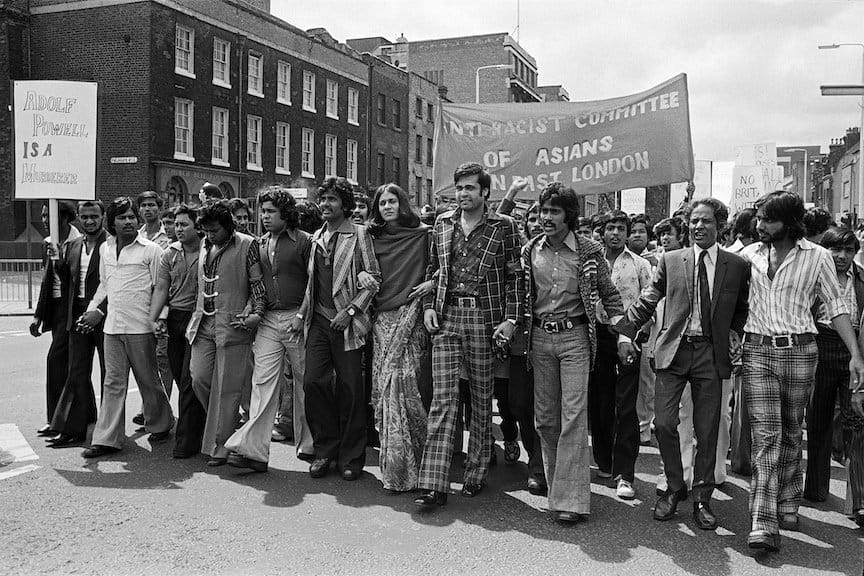

This newsletter recently featured the work of the ensemble Dishari, a group of Bangladeshi musicians and trade unionists formed to promote cross-cultural exchange in the aftermath of the brutal murder of textile worker Altab Ali by white supremacists on May 4th, 1978. Ten days later, 10,000 Bengalis marched with Ali’s coffin to Whitehall, supported by a massive withdrawal of labour and services by Asian shopkeepers and workers. The ANL had only an auxiliary part to play in these demonstrations, working alongside the Asian-led Action Committee Against Racial Attacks (ACARA) and the Bangladeshi Youth Movement (BYM).

The BYM was one of many organizations known collectively as the Asian Youth Movement (AYM). The earliest of these groups was launched on August 15th, 1969 in Gravesend, Kent, at a celebration of India's independence from British rule; and was quickly followed by cells in Birmingham, Luton, and more. While many of these groups functioned as mutual aid societies, sustaining their communities for want of ready services, they also functioned along lines of self-defence. The BYM was hardly the only group formed out of tragedy; in 1976, the Southall Youth Movement (SYM) held their first meeting in response to the murder of Sikh student Gurdip Singh Chaggar by neo-Nazi skinheads.

As urgently, these groups opposed police brutality and legal intimidation with the same force and frequency that they were forced to fight back civilian vigilantism. Courthouse demonstrations and pickets were a common tactic: in 1982, the Sheffield Youth Movement rushed to the defence of Ahmed Khan, arrested for defending himself during a racially motivated attack on the restaurant where he worked; and in that same year, the AYM mobilized behind the defense of the Newham 8, a group of teenagers arrested by plainclothes police for fighting back against the mobbing of Asian students outside Little Ilford School. This campaign was led by the Newham Monitoring Project, a prototypical "cop watch" formed in response to the 1980 murder of teenager Akhtar Ali Baig.

While composed of non-white and immigrant members, these groups were not based on narrow ethnocultural criteria, and were quite porous with respect to local facets of the immigrant experience. The Bradford Blacks and Bradford Asian Youth Movement, reformed from the Indian Progressive Youth Association in order to expand its cultural scope, worked nearly as one in their anti-fascist efforts; and Balraj Purewal of the Southall Youth Movement recalls the motivation behind their more unifying nomenclature: “We called ourselves Southall Youth Movement because we were not a minority in Southall. Saying ‘Asian’ made it sound like we were a special thing but we were the youth of Southall.’”

If anything, the multiracial solidarity that the Clash had to strain to glimpse was a fait accompli for many Black and Asian youth in Britain; and in the lexicon of their movements, a Black identity framework was often used to encompass South Asian and Caribbean experiences of an adverse society. As Anandi Ramamurthy explains in her work on the history of the AYM, this Blackness was a secular, multinational political identity above all else, and facilitated a wide level of cooperation between many migrant groups.

As the far-right continues to grow and we look to the heyday of the ANL and RAR to inspire our resistance, we should be as keenly attuned to these lesser known and little celebrated histories. Of course, there's an illustrative tension at play in these charged examples from the past; where to overemphasize the spectacle of RAR risks populism, and to champion the defensive posture of the AYM risks communitarianism—two sides of the same coin. To some degree, a socialist front like the ANL can mediate these necessary moments, but ultimately, the present day requires new collective leadership no less than a new tactics.

There's no doubt in my mind that this means another Carnival Against the Nazis, and another, and another; but it's after the gig and when the protests have dispersed that the struggle against fascism really begins. That means organizing with our neighbours, for a single, all-inclusive riot against capitalist rule; for real health and safety; and ultimately, for peace and socialism. The far-right is clear in its aims, however reckless its street-ready section, and the movements that we gather must see far beyond their small horizons.