Enhanced Techniques

On the Art of Guantánamo Bay

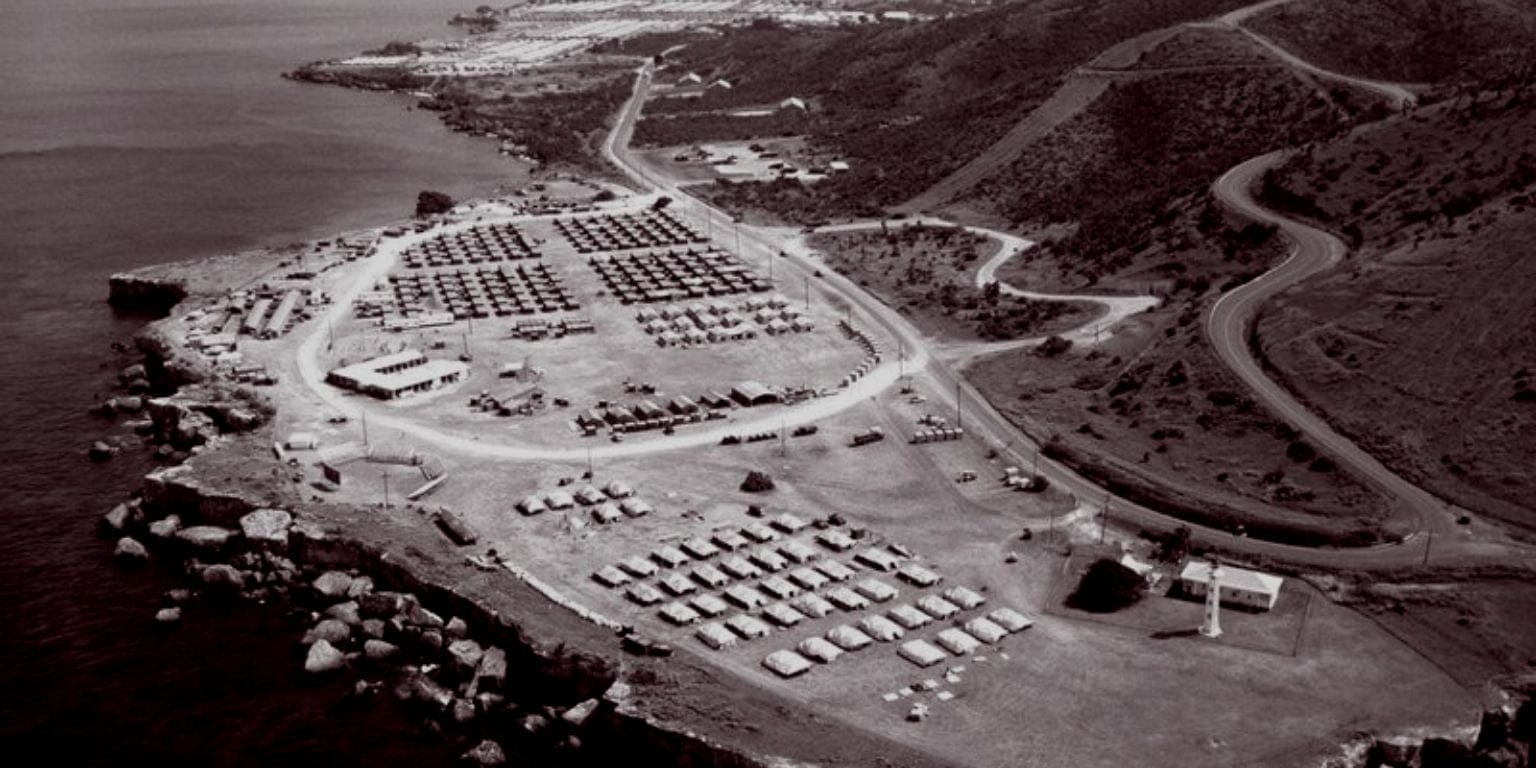

For all its hundreds of bases around the world, few outposts of United States imperialism are so controversial as the naval base at Guantánamo Bay—where a long colonial legacy in the Caribbean becomes a taunting front of Cold War, and a focal point of the so-called War on Terror at the outset of the twenty-first century. But this illegal occupation of Cuban soil by the United States has a long history apart from the high-profile tortures and detainments that have made it a household name, including the detention of thousands of Haitian refugees in the early nineties, or the maintenance of tent cities for Cuban "rafters" caught between jurisdictions.

The US base at Guantánamo Bay dates back to the Spanish-American War, and the current lease, fixing the price of the land at $2000 a year in gold coin, dates from 1903. The US has maintained this presence since, through the early decades of independence; the brutal US-backed Batista dictatorship; and more flagrantly, the span of the Cuban Revolution to date. While the currency has changed, the rent has not; and the US still sends cheques to the government of Cuba for $4,085 each year, which the island's revolutionary government consistently refuses to deposit. (A single payment was accepted by mistake during a transitional period in 1959.)

In spite of the clear illegality of this occupation and its importance as a Cold War military front, "Gitmo’s" present infamy belongs squarely to the twenty-first century, and George W. Bush's reactivation of the Guantánamo Bay Detention Camp for "enemy combatants" in 2002. In this era of exceptional state power, Bush used occupied Cuban soil to circumvent the minimal protections of the US constitution, subjecting up to 780 known prisoners to extravagant tortures.

Only 15 of these prisoners remain, but earlier this year, President Trump announced his intent to reactivate the facility as an effective concentration camp for up to 30,000 deportees from the United States—starting with rumoured Venezuelan "gang members," as if to flout Cuba’s closest diplomatic relationships. This is a preposterous figure, where the prison itself is constructed to hold only 400 inmates at a time; but as service members set about erecting tents across the island, it appeared that Trump was reestablishing a costly waystation between the US and South America for large numbers of deportees.

After this initial outburst from the White House, news of Guantánamo slowed to an ominous silence; but according to a class action complaint against the US State Department, "since February 4, 2025, the government has held approximately 500 people in immigration detention at Guantánamo, at a reported cost of more than $40 million, or approximately $100,000 per day per detainee." It's unclear how long any of these 500 people remained at the prison, where recent estimates indicate that the population has swelled to only several dozen since Trump's initial announcement. But this costly program clearly means to insult Cuban sovereignty as it facilitates a dangerous outburst of military aggression in the region.

Art in Captivity

Even as Trump escalates against Cuba and fixates upon the island base, Guantánamo still seems to evoke the Bush era in the popular imaginary; or its aftermath under Obama, who campaigned on a pledge to shut the prison down for good. Needless to say he did not, and Guantánamo became a flashpoint and baton in a disappointing succession of powers. Rather than close the prison, Obama attemped to sanitize its image, initiating a range of intramural and educational activities for those inmates remaining, including high-profile art classes.

Much has been written of the prisoner artwork of Guantánamo Bay, which makes an eerie exhibition at the junction of hard and soft power. As former inmate Mansoor Adayfi recalls, "our artwork wasn’t just made by us, it was treated like us: catalogued, controlled, abused—and in many cases, tortured, disappeared, or destroyed." This implicit pact—between the treatment of an artefact and the physical integrity of its creator—changes the reception of these works, as it shapes the stakes of a bitter legal contest around the ownership of the work.

Until a partial reversal in 2023, the US government claimed any art created in the prison as state property. This confiscatory policy was briefly abandoned by the Biden administration, but restored by Trump after a 2018 exhibition at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York displayed over one hundred prisoner artworks, piercing a veil of silence around the base and its practices. In a rare exception to this rule, Yemeni artist and longtime detainee Moath al-Alwi was permitted to take most of his artworks with him upon extradition to Oman earlier this year—but this outcome no doubt follows from strong lobbying as well as his heightened artistic profile, and by no means corresponds to changes in policy.

The artists of Guantánamo choose to represent their experience in various media, and their collective output often settles upon strikingly similar motifs. Disfigured visions of the Statue of Liberty recur, her face concealed beneath a torture hood or juxtaposed with barbed wire and cages; ocean vistas evoke both turbulent scenes of migration and the open expanse beyond the naval base and harbour. (The show at John Jay College was entitled 'Ode to the Sea.') Developing this theme, Moath al-Alwi is best known for his meticulously detailed series of sea-faring vessels—tactile, mixed media sculptures assembled of found objects in his cell. This material carries a signatory dimension, and al-Alwi's art prominently, ironically incorporates the US government stamp of approval. "It carries the truth they tried to hide," al-Alwi explains: "It’s a testimony to their injustice and cruelty and to our resistance and resilience."

Every artwork produced within the prison was vetted in this fashion before public display, to ensure that the artist hadn't enciphered any seditious content or outside communication in their work. Such control clearly intends to dehumanize the inmate-artists, visiting further movement restriction upon the alienable affects of their artistic labour. But as Alexandra Moore and Elizabeth Swanson explain in an edited volume on al-Alwi, this creative work harbours a crucial evidentiary, even forensic, significance in its very materiality. In this respect, it's not just that the work is blocked from view: so too are the unacceptable conditions it would encode or elliptically depict.

Art of Captivity

Alongside these captive artworks, the sheer volume of negative publicity around Guantánamo has provoked a range of conceptual artworks from outside the prison population. And while the artwork produced under by those insight tends to allegorical deployments of national symbols or to suggestive shorescapes, these documentary works tend to jam or reconfigure the archival traces of the War on Terror, adapting the means of the penal bureaucracy that they thematize or confront.

In her depictions of Guantánamo, lawyer and photographer Debi Cornwall depicts the stifling effects of the prison through an interloper's eyes, folding the legal difficulty faced by visitors into the artwork itself. As one expects, the obstacles are numerous: for example, the prison typically permits only digital photography so that military censors can immediately vet each image; and even after Cornwall was granted permission to shoot on film, drawing upon her legal training to negotiate terms of access, each roll had to be developed under military supervision.

Such vetting infiltrates the content of the pictures, too, where Cornwall's photographs depict only the facility itself, leaving the viewer to imagine all that its walls have witnessed. As with the prisoner artwork, where every artefact represents the physical persistence of its creator, sentimental objects stand in for inmates—prayer rugs and clothing laid out for the day, or toiletries and other minimal personal effects. These scenes are intimate and ominous at once, alluding to the smallest rituals but plausibly abandoned, as if the remaindered property of the disappeared.

Cornwall's Guantánamo photography reexpresses the strictures of the prison environment, joining a contemporary subgenre of documentary artworks that make a formal approach to proscribed content—call it bureaucratic conceptualism. Whether in writing or photography, this new formalism follows the proliferation of data and image in the twenty-first century—from declassified ledgers of past atrocities to the glut of information collected in the wake of the Patriot Act—in order to commemorate the many disappearances and detentions of the neoliberal era on a global scale. And as the state operates at ever-greater distance from popular scrutiny, even as it infiltrates the digital minutiae of everyday life, much abstract and conceptual art has found a political calling in its unique capacity to represent that which does not appear.

This paradoxical task poses interesting problems for photography in particular, where the visual field comprises just so many positive appearances. Within the syntax of the photograph, negation typically proceeds by figural substitution or subtraction, two basic operations of Cornwall's prison pictures. But these vacated cells find their positive counterpart in an equally stunning series of portraits, depicting former inmates in the countries to which they were eventually released.

In this suite, entitled 'Beyond Gitmo,' Cornwall photographs her subjects from behind—facing their new environs, from outdoor amphitheatres to town plazas, with history at their back. Where her unpeopled prison photographs place the viewer in a first-person perspective, corresponding to the limited view of each cell's occupant, these post-detention portraits appear to draw back from this coincident frame, placing the former prisoner between our witness and the wider world. It's a simple, moving gesture, and emboldens each tentative figure without disclosing their identity. If anything, this effacement and its framing evokes agency and purpose; a romantic Rückenfigur, its subject standing down whatever challenges are still to come.

Lanterns at Guantánamo

The negative witnessing described above varies a great deal depending on the artist's media; and the enormity of Guantánamo has motivated a range of poetry and sound art at the threshold of legible experience in addition to the better-travelled visual record. Some of this work is legible as journalism, such as Laura Poitras' repurposing of recorded interrogations, while other contributions verge on docudrama, such as Gregory Whitehead's recomposition and narration of the interrogation log corresponding to "detainee 063," obtained through Wikileaks.

In Lanterns at Guantánamo, poet and critic Jordan Scott details the strict terms of his access to the prison base for the purposes of a research trip in 2015—the same year as Cornwall's infiltration. As Scott explains, his research at Guantánamo was initially concerned with the prison's oral cultures, and more specifically with instances of dysfluent speech as it shapes and responds to scenes of torture and interrogation. Scott’s work on dysfluency (“destroying the good sense of a word”) stems from his own experience of speaking with a stutter; but his interest in this penal setting concerns the importance of clear speech to the security state, where FBI manuals describe dysfluencies as wilfully evasive or self-incriminating.

That said, Scott faced an all-embracing institutional silence on the topic of the “enhanced interrogation techniques” for which Guantánamo is known—and so his interest in the disarticulation of subjectivity by the prison apparatus began to pursue the form of a signifying silence instead. Rather than speak with either state interrogators or their captors, Scott turned his attention to the generic acoustic conditions of interrogation as such, recording the ambient environmental sounds of his time in the prison facility:

I quickly realized that my time at Gitmo would consist in navigating this kind of institutional silence. I decided that in the absence of both interrogators and interrogated, I wanted access to Gitmo not in order to represent (or describe) the detained and interrogated men, but rather to document the nature of their speechlessness and the conditions of their absence.

“The recordings were often interrupted by my breathing, the rustling of fabric, or my footsteps,” Scott continues: “These mediating traces form a sonic register of the troubling ethics of my presence at Gitmo.” In his disarming recordings, the incidental sounds of the recordist index a relative physical ease about a place of confinement, as regional keynotes like birdsong beautify the record of a problematic visitation.

As Scott notes, it’s unclear why he was permitted access to the facilities in the first place. According to the Public Affairs Representatives of the US Southern Command, he was “their first poet—outside the walls,” a fleeting acknowledgement of the detainees’ full humanity and creative aspiration. This morsel of recognition haunts Scott’s understanding of his visit and its unstated terms, tightly restricting any representative takeaway. How then to represent the unrepresentable?

The Tragedy of the Disappeared

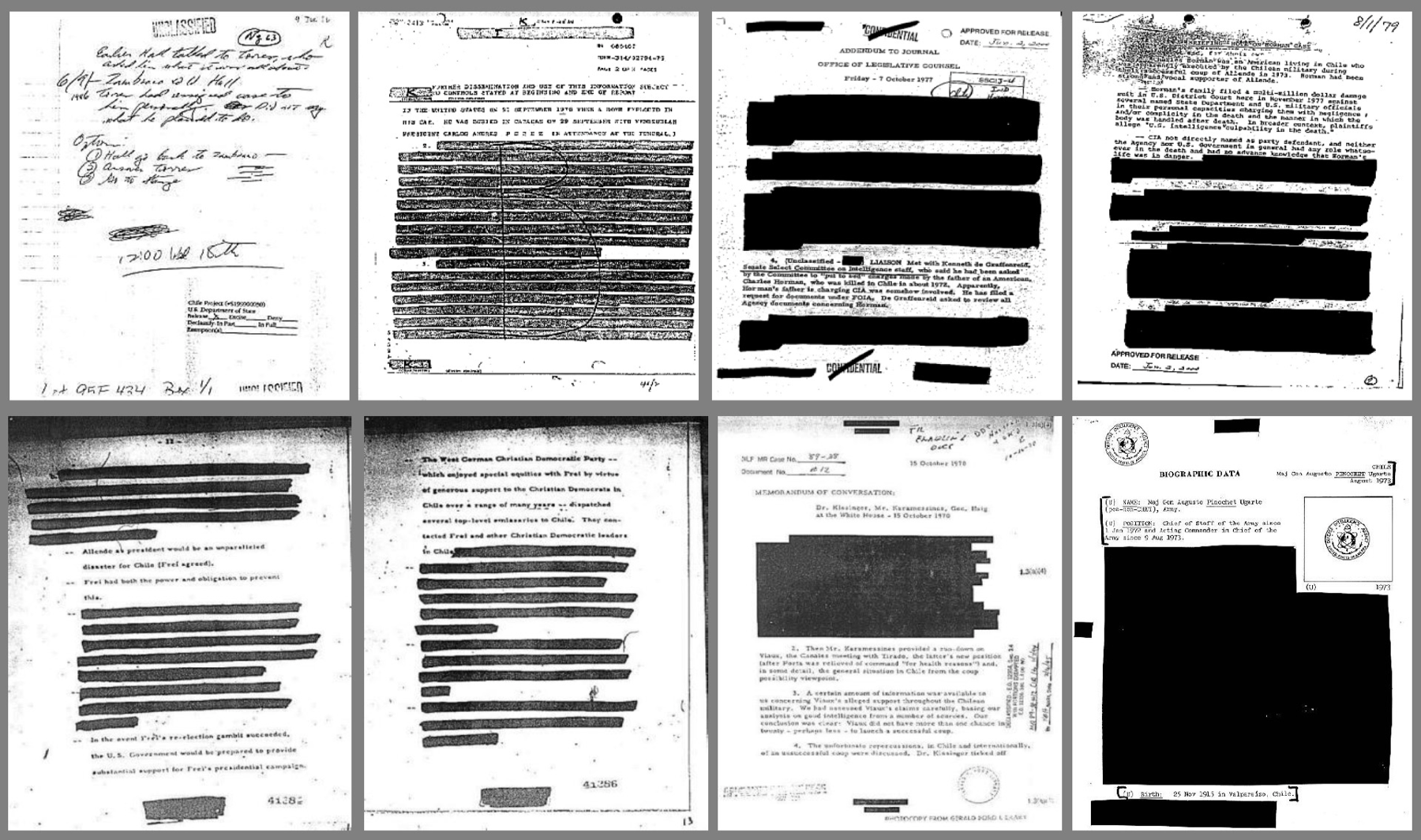

In his book Sonic Agency, theorist Brandon Labelle describes a range of listening practices appropriate to “the tragedy of the disappeared” in Chile, though these methods are pertinent to many other political geographies marked by periods of violent dictatorship or military occupation. Of particular significance is the work of Voluspa Jarpa, which takes up the CIA’s recently declassified (although heavily redacted) archive of the Pinochet era.

Jarpa’s La Biblioteca de la NO-Historia, a series of bookworks spanning 2010-2012, republishes excerpts from thousands of these blacked-out and repressive reports as an opaque visual poetry, commemorative of countless individuals who are not nameless but unnamed. For LaBelle, such artistic gestures strive to communicate by “shadowed routes, at times bypassing language altogether,” adapting to conditions of fear and repression.

The leap from an illegible—silent and silenced—text to a strictly acousmatic victomology is left to the reader’s own associations in LaBelle’s demonstration, which sets forth a visual paradigm of audible absence. (Or in LaBelle’s own words, “the absence that refuses to be silenced and yet which cannot truly resound in the open.”) But the relationship of a poetics of erasure to a sonified practice of “bracketing” is only analogical or implied in LaBelle's demonstration. What kind of attention does the barred text command of a reader, that its surface commends sonic experience instead?

Scott’s work at Guantánamo does more to develop the connection between these parallel practices of subjective tracing, both of which make an oblique approach to the body detained. In one sense, Scott’s description of dysfluency implies a kind of self-redacted speech, marked for suspicion as the multiplication of sonic information over semantic content effectively enveils the speaker. But Lanterns sets out from a careful consideration of non-forthcoming or inhibited speech, and its visualization by official or poetic acts of erasure.

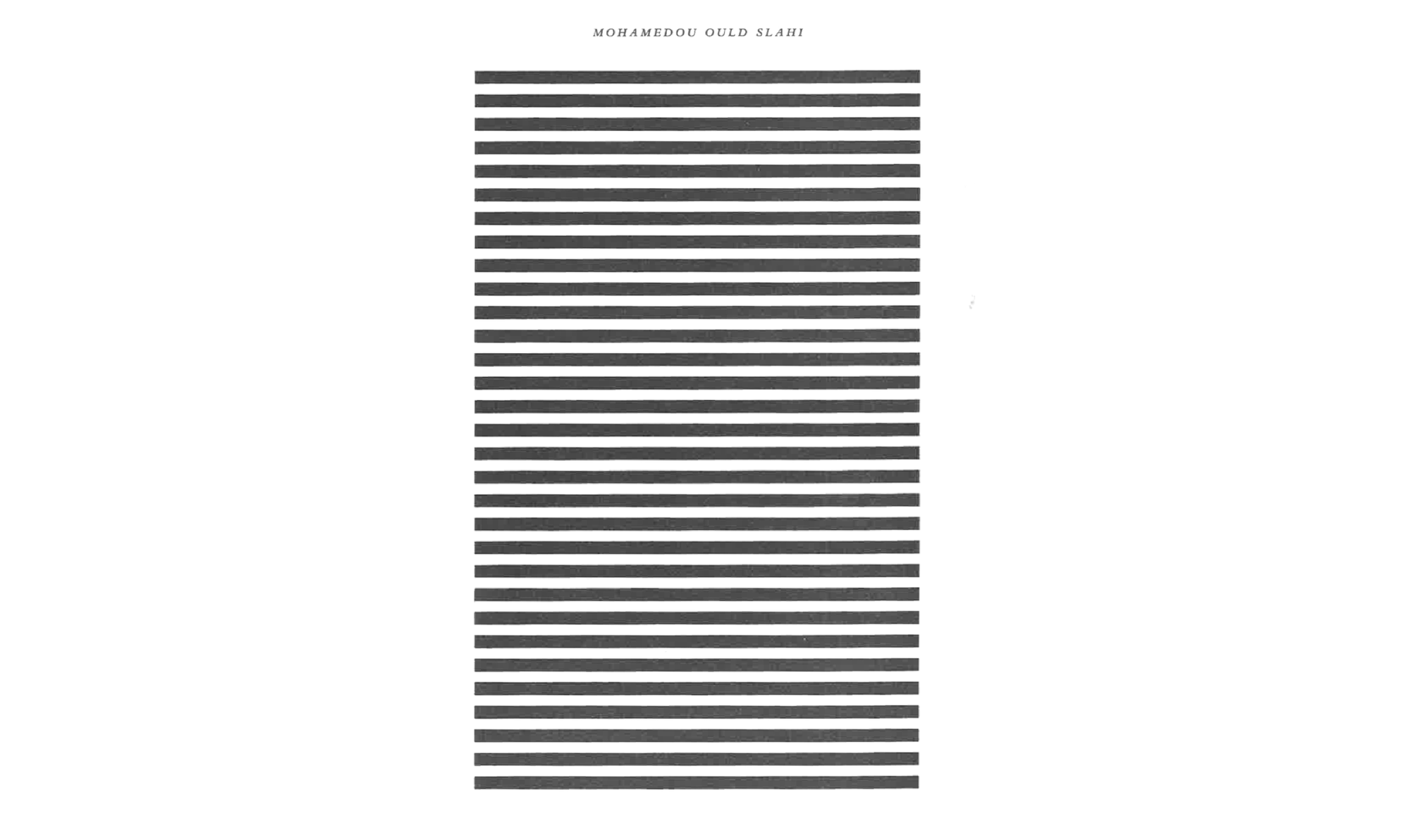

Scott’s own journal opens with a meditation on Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s Guantánamo Diary, in which Slahi recounts a poem shared during an interrogation session. In the text, this poem appears as a full page of solid black lines, like closed blinds or horizontal bars, extending margin to margin. No words protrude, but this visual silence implies a flush poetry on the other side of its extinguishment.

Like Labelle, Scott sees the redacted text as a complex play between absence and presence—an emblem of an "impossible form" or a visual scoring of the un-overheard. And in the course of Scott's own reconnaissance, an aesthetic attention to absenting form begins to draw unlikely parallels:

When I think about these various noises—air conditioners, wind in the grass, birds—I am drawn to the similarities between ambient vacancies and visual redactions. When I look at Slahi’s censored poem, I see a visual equivalent to the air conditioner’s drone: flat, empty spaces that mark sites of total domination.

Because of this apparent emptiness, Scott's field recordings manage to escape close scrutiny or confiscation by prison censors. These recordings, like Cornwall's photographs, do not depict the prisoners themselves but the sensory manifold or scenery of their confinement, including regional fauna and other sonic presences; sounds and airs of the isle itself, notwithstanding occupation.

But who gets to hear what? In what rarefied moment would a detainee hear a birdcall, the wind, or the sea? The pastoral sounds were always mingled with an insistent mechanical drone, a mundane signal that here could be anywhere, any time, any place… and yet the signature remains intact; the ambient sounds of Gitmo are as recognizable as the blacked-out lines of a redacted poem.

This comparison seems counterintuitive at first, where it conflates the sonic repletion or excessive meaning before and during speech with the after-effects of censorship. In the recordings described above, the mechanical drone and other indomitable keynotes of the prison landscape are not so much obliterative of experience as bracketed from its recollection—though such features also function to drown out the sounds of torture and interrogation in a prison environment.

To my understanding, the ambience eluding censorship makes a stronger analogy to the empty page beneath every redacted transcript. Or still more persuasively, one might compare the innocuous morsels of language that go unredacted in official releases to the neglected ambience that Scott records, which bears no comprehensible witness where authorities are concerned.

The broadsides of Carlos Soto-Román, for example, take the heavily censored Pinochet archive as their basis, but preserve the marginalia and annotations of the various offices through which these documents have passed. This human interference, in an unstable hand, reveals nothing of the troubling incident each document would properly commemorate, which Soto-Román otherwise whites out. Rather, the visual noise of bureaucracy only betrays the passage of the document from desk to desk—a contentless confessional on the part of countless participants behind the scenes.

In Scott's description, however, his recordings escape censorship because they are perceived as pre-redacted, and lacking any telling content whatsoever: "Ambient recordings are a kind of empty form; they resonate with the redacted poem." Just as prisoner accounts of Guantánamo must undergo severe modification, barring all but the gaping page beneath, Scott's overseers only permit him to document the backdrop to the myriad unheard voices of the prison.

As such, Scott’s reconnaissance makes an acoustic complement to a legally fixated genre of conceptual art—a kind of civilian prison memoir that concerns itself less with firsthand anecdote than with a meta-evidentiary archive of subjective erasure. In both instances, the bracketing practices of contemporary art, intended to draw one’s attention to the parameters of experience, are thematically referred to the strictures of confinement. Lanterns thus represents the empty form of penal discipline, which, once furnished, requests bodily cargo.

Travel Considerations

While these artistic methods are often characterized as formal responses to the era of the Patriot Act and the management of information by an exceptional state, it’s clear from the pertinence of these same gestures to the Pinochet archive that the methods of twenty-first century regimes draw from countless crimes of the past. With this in mind, the longer shadow of Guantanamo requires that we resituate these artworks in the aftermath (and present) of the so-called Cold War.

To do so can only refine our understanding of imperialist means in the present—but as Cuba’s perseverance and its encirclement clearly shows, the Cold War never ended, and it thaws today. As US aggression mounts in Latin America and the Caribbean, already resembling an undeclared war on Venezuela and its allies, the Cuban vantage is of paramount importance.

That said, it's hard to rally solidarity from art, or to strategize from most of the outsider artworks discussed above. At their best, these works tend to understate the agency of those inside, perceiving the detainees as victims first and foremost, and then in a spectral guise. What pertinence might these techniques have to the necessary effort ahead, and the defence of Latin American sovereignty from US imperialism? Do any of these gestures bear upon the present and future uses of Guantánamo, or do these works simply reduce the US-occupied portion of Cuba to a place of exception on the outskirts of a dying empire?

In contrast to these documentary representations, artist Thomas Altheimer has mounted a sonic attack on the island base, blasting strains of Beethoven's third symphony at the facility in hopes of "turning Guantánamo Bay into a huge European, neo-colonial, spatial installation." The seaborn performance was apparently almost inaudible amid gale force winds, besides which the gesture feels simply redundant: Guantánamo is a colonial holdover, wherein audio torture is prevalent. Launched from Jamaica, this performance at least apprehends the strategic location of Cuba, but such stunting directly flouts the island's sovereign inhabitants.

Altheimer's proposal to transform the prison facility into an installation of sorts borrows precedent from many processes of institutional reckoning the world over, though other such artistic visions of Guantánamo propose a bureaucratic counterforce to the occupation on its own terms. The Guantánamo Bay Museum of Art and History, a fictional online gallery by artist Ian Alan Paul, describes a range of unrealized conceptual works corresponding to the methods deployed in the prison and to its commemoration. Likely modelled on the transformation of carceral space throughout Chile after Pinochet, this piece of conceptual web art places itself in a counterfactual timeline where Obama made good on his pledge to close the prison doors once and for all:

When the last detention facility in Guantánamo Bay was officially decommissioned in 2010, an international team of artists, curators and architects began planning and designing a museum that would take the place of the detention facility - a little less than two years later, their work became reality. The purpose of the collaboration was both remember the human rights abuses that occurred while the prison was in operation while also providing a framework for combatting contemporary human rights abuses that continue to persist. The museum actively seeks to draw together a dynamic and mobile collectivity of artists, theorists, and other members of the public to create the conditions for reflection and imagination. The Guantánamo Bay Museum of Art and History officially opened its doors to the public in August of 2012.

This description poses its own problems, however—supposing Guantánamo Bay to exist in a borderless world governed by independent curators among "coalitional social movements." Nowhere in this imaginary scenario does the artist mention Cuban jurisdiction, nor apparently has the revolutionary government of Cuba played any part in the fictional liberation of this land from US occupation. However thoughtful the 'exhibition' itself, this oversight fatally cuts against its vision of liberation, which is led in this fanciful instance by the consulting intellegentsia of the United States.

Too often the enormity of Guantánamo prison has prompted artists to implicitly repeat the US annexation of this land in their humanitarian reply to unacceptable conditions—effectively forgetting the longer colonial and military history that culminates in the prison's placement on foreign soil. Not that these artworks need concern themselves with the terms of US withdrawal per se—but in spite of its eccentric jurisdiction, we exceptionalize Guantánamo at great political risk.

Even from this cursory survey, it's clear that the persistent fascination of artists with the detention camp at Guantánamo Bay doesn't necessarily follow from a consistent politics or a deeper relationship to the region. Rather, these many outside approaches to the institution treat its protocols and architecture as an aestheticizing apparatus in themselves—as if every prison were a future museum of its present infamy. The reasons for this formal correspondence are worth longer comment, and as surely concern the conditions of artistic production among detainees, to say nothing of the ease with which Guantánamo was transformed into a factory of artistic dissent in spite of its longer mission.

As we try to think alongside longer decolonial and anti-imperialist aspirations in the region, it may be that the best art that the west can offer is that which adds nothing, but places an ear to the present. Cuba doesn't need a foreign intervention, artistic or otherwise: Cuba needs an international audience for its own demands, including the immediate closure of the naval base at Guantánamo Bay.

World Balance

Incidentally, I was in Havana for the chaotic first week of the Trump presidency, where his announcement of the reactivation of Guantánamo Prison coincided with the opening plenum of the Sixth Conference on World Balance. At the closing ceremony, President Miguel Díaz-Canel responded defiantly to this provocation, drawing on the memory of José Marti and of Cuba's long fight for independence:

I am talking about Cuba, from which the United States stole a piece of land in the name of a friendship it never honored by using that territory, illegally occupied for more than a century, as a military base and prison where people the empire declares enemies and guilty, most of the time without a single evidence of their crime, are tortured and locked up in a legal limbo.

As if this infamy, which has been condemned hundreds of times by international tribunals, were not enough, now we are told that 30,000 deportees will be sent to the US Naval Base in Guantánamo. Once again the illegality, the disregard of international treaties, and the unacceptable idea that there are countries and people superior to the rest of humanity.

In spite of all the sorrows, as we say here, and the presidential orders of the masters of the world, we will not remain silent in the face of infamy, nor will we lose confidence and faith in human betterment, future life and the usefulness of virtue.

Díaz-Canel's words were met with resounding applause, and I felt lucky to witness the first week of Trump's second presidency from a place of global resistance. Where so much of US strategy proceeds by regional containment and isolation, gatherings like this refute the US worldview in their very openness. But this call likely recommends not just renewed attention to Guantánamo and other US bases, but new methods of representation by which to register distant opposition.

For all of those more patient artworks that have either infiltrated or escaped Guantánamo, the persistence of this Cold War relic in the present must be better prosecuted, catalogued, and understood. The works discussed above may help this understanding along; and yet, particularly insofar as they borrow form and matter from the institution of Guantánamo itself, they remain ambiguous—for any problems posed by truly conscious art must necessarily await political reply.

I briefly reported back on the Sixth Conference on World Balance in an episode of In Defence of the Revolution from earlier this year: