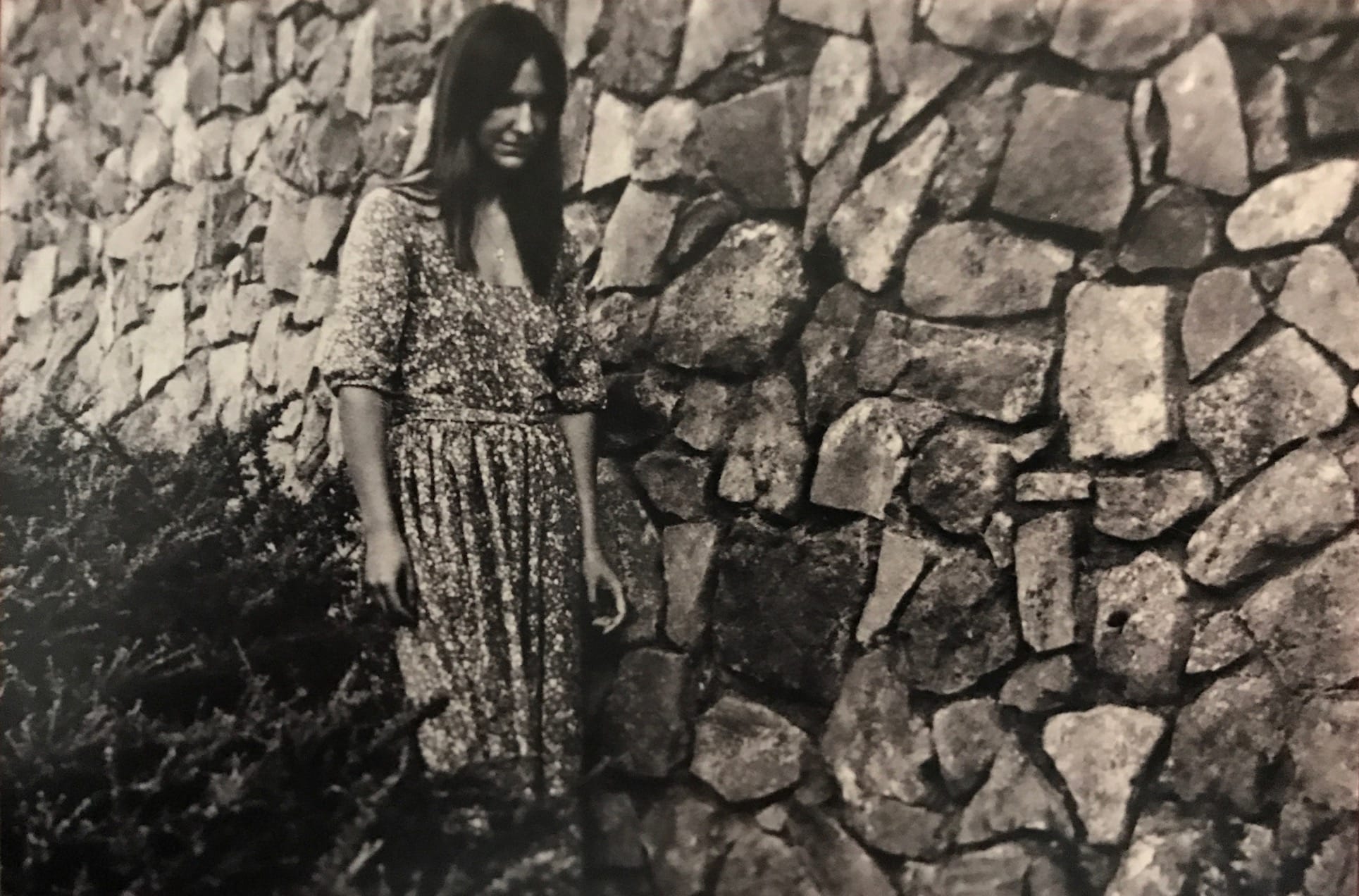

For Patty Waters

Two Nights in Brooklyn and Houston

To all familiar, Patty Waters was an icon of avant-garde jazz—a Brontë sister's torch singer, her every syllable imbued with pressing secrecy. Even today, her 1965 debut stands out from ESP-Disk's vast discography; matching a set of Waters' compositions, graced with the wisdom of longing, to a scalding rendition of the Scottish folk song ‘Black is the Color of My True Love’s Hair.’

'Black is the Color' has been a jazz staple since Nina Simone’s sultry resuscitation in 1959; but Waters’ version is a different beast, pairing an alternately screamed and whispered vocal with tumultuous backing. Pianist Burton Greene plays the piano from the inside out, and the entire group strains at the limits of musical idiom, maintaining a breakdown for almost a quarter hour. If the A side of Sings is haunted, the B side is surely possessed.

In spite of only intermittent performances since her iconic recordings of the 1960s, Waters’ reputation continued to grow, affirmed by the praise of subsequent generations of listeners and the warmth of reception that attended her select appearances. And in a gift to admirers, both of her 2018 concerts—in Brooklyn and Houston respectively—were recorded for near-simultaneous release, featuring Burton Greene on piano, Barry Altschul on drums, and Mario Pavone on bass. These two documents are distinctly indispensable in spite of overlapping setlists; and after the passing of Waters last month, following Pavone and Greene in 2021, a band of this pedigree should be cherished.

Released by New York's Blank Forms, Live presents selections from the group’s April 5th performance at the First Unitarian Congregational Society in Brooklyn; a gig that the label and curatorial platform also produced. From the first chords of ‘You’ve Changed,’ a song forever altered by the voice of Billie Holiday, a mist of wistfulness envelops the listener. It's a coy choice of opener, addressing the passage of time before a multigenerational audience, and Waters sings with tremulous incredulity.

Live gathers many such exquisitely weird, or deceptively subdued, standards; the emphatically slurred chords of ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry’ purr below Greene’s fingers after Waters’ falling intonation, until the melody abruptly dissipates in a repetitive whimper; while Pavone and Altschul, best known for their chemistry in Paul Bley’s trio, communicate deftly across a searching rendition of ‘Lover Man.’ Side A concludes with Waters’ best known composition, and the first track from her debut album, ‘Moon, Don’t Come Up Tonight.’ The melody’s descent remains as haunting here as in its initial, stripped-down version, but Greene invites the lyric’s lovesick wanderer inside, adding a bluesy warmth, as Altschul embellishes the spacious phrasing with near-scalar fills and beautiful brushwork.

A deconstructed medley of ‘Strange Fruit’ and ‘Nature Boy’—two powerfully overdetermined staples of the Great American Songbook, popularized by Billie Holiday and Nat King Cole respectively—begins with a tolling note in the piano's lower depths. For this central statement, the music dissolves into an array of percussive effects distributed across the entire group, making the seam between the two songs a matter of lyric discretion. This sequence links two utterly disparate pastorals: the upsetting scenery of ‘Strange Fruit,’ which describes a lynching by way of its disinterested landscape, and the mysterious visitation of ‘Nature Boy,’ which takes on a haunted character as a result.

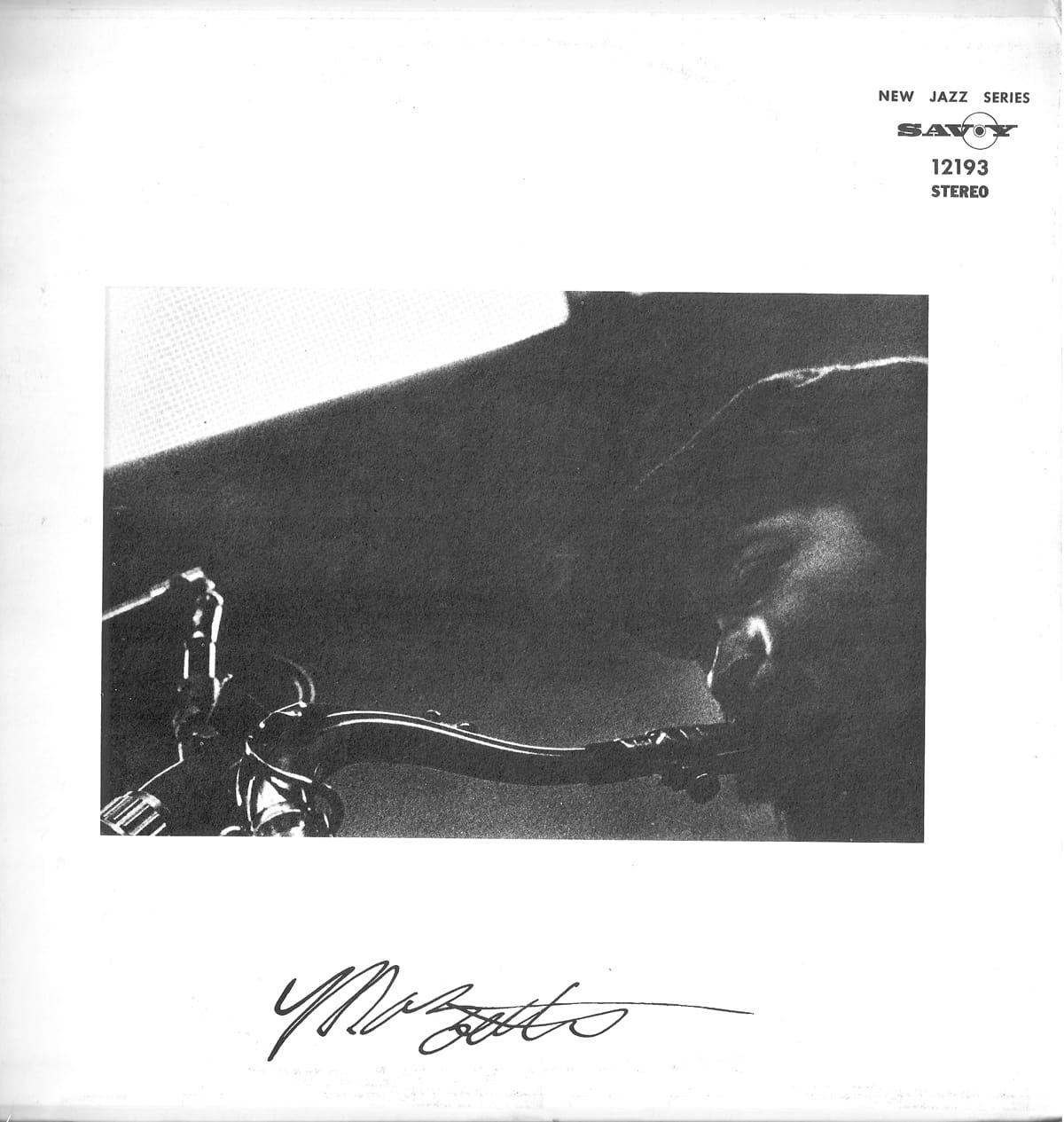

This suggestive pairing is followed by a version of Ornette Coleman’s ‘Lonely Woman,’ featuring Waters’ original words. This is one of several lyric versions in circulation; Waters’ version was previously performed by the Marzette Watts Ensemble, while another interpretation by Margo Guryan has been recorded by Chris Connor, Freda Payne, Radka Toneff, and others. Here Waters’ vocal weeps with a pathos that other, more restrained versions avoid; and skittish cymbals summon the inedible original.

Released by Clean Feed Records, An Evening in Houston was recorded only days after the Brooklyn concert, on April 9th, as part of the Nameless Sound series. The album opens with a palpitating version of ‘You’re My Thrill,’ a duo for voice and drums. Altschul’s brushes introduce the tune, and Waters approaches its familiar lyric as a loose recitative, as if discovering the words in air. ‘Moon, Don’t Come Out Tonight’ sounds somehow woozier, more languid, as Waters’ voice—beseeching, searching, psithuristic—gives the impression of a whispered secret.

‘Lonely Woman,’ which began in Brooklyn as an ominous piano invocation, opens on unaccompanied tremor in the voice, a moment of mimetic inspiration. Moody and wounded, this take is a highlight. So is a stripped down version of the standard ‘Don’t Explain,’ in which Pavone’s bass and Waters’ vocal circle each other conversationally. “You know I love you,” Waters sings, at which point a simmering snare picks up beneath the duo; subtle as a change in temperature. Greene’s lightly prepared piano announces ‘Hush Little Baby,’ an abstracted nursery rhyme that appeared on Waters’ second album, 1966’s College Tour. On the original recording, a fricative hiss blends the sizzle of the cymbals in a menaced lullaby. Here, Waters repeats the lyric pleadingly, intelligibly, as the band fidgets beneath.

Both Brooklyn and Austin sets and their corresponding albums conclude with ‘Wild is the Wind,’ which originally appears on College Tour as a companion piece to ‘Black is the Color of My True Love’s Hair.’ These songs were staples of Nina Simone’s repertory, debuting on her 1959 album Nina Simone at Town Hall, and Waters and company give them a similarly chilling treatment decades later. In 1966, Waters makes a central incantation of the word ‘black'; in 2018, she catches upon the keyword ‘wild,’ becoming so.

These releases are not companion pieces in any sense; perhaps they are echoes of a sort. But each setlist gives the uncanny feeling of hearing something familiar for the first time. I was at the Brooklyn concert that produced the Live LP, watching Burton Greene's hands from a balcony and savouring the whispered shivers of a voice out of time. Reliving this performance now, I am awash in gratitude for all the moments it preserves, and for the life in song that Patty Waters shared.

A version of this review appeared in the Free Jazz Collective blog in May 2020; it appears here lightly revised, the tense adjusted, in memoriam of Patty Waters, who passed on June 29th, 2024.