Here is a Human Being

On Spotify and Ancestry.com

There are too many good reasons to part ways with Spotify; from CEO Daniel Ek's investment in military technology to its parasitic payment model, heaping insult on financial injury for hundreds of thousands of barely subsisting artists. The scandal of Spotify is well-understood by almost everyone, and yet its subscriber base grows. This isn't just a question of consumer ease, but music marketing as well. Even as Spotify endangers artist livelihoods, its misleading metrics have become fully incorporated into the survival strategies of independent musicians, deepening our dependency on profiling, predatory tech. Needless to say, there's a counter-movement to grow here, and I'm looking forward to reading journalist Liz Pelly's Mood Machine, publishing next month, for a critical rundown of the streaming paradigm and Spotify's intensifying war on music.

Today, however, on the occasion of everybody posting their annual 'Spotify Wrapped' playlists, I thought to share this piece I wrote for Popula in 2018—on Spotify's partnership with Ancestry.com, the cultural ramifications of data collection, and the difficulty of seeking one's deeper identity in the algorithm.

"Listen to me, there is an echo which travels along faultlines; it comes from their music. The strange music of the people."

Marcia Douglas, The Marvellous Equations of the Dread: A Novel in Bass Riddim

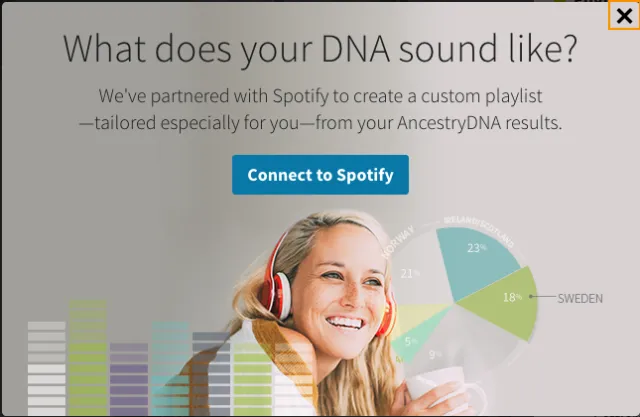

“If you could listen to your DNA, what would it sound like?” With this question, Ancestry.com, the largest for-profit genealogy company in the world, announced its new partnership with music streaming platform Spotify last week. The service, Ancestry.com explains, will provide a soundtrack based on your own family tree. These playlists promise an experience of one's own roots—effectively objectifying a customer’s heritage for consumption, and projecting the predictive, user-friendly texture of the online both into the body and back in time.

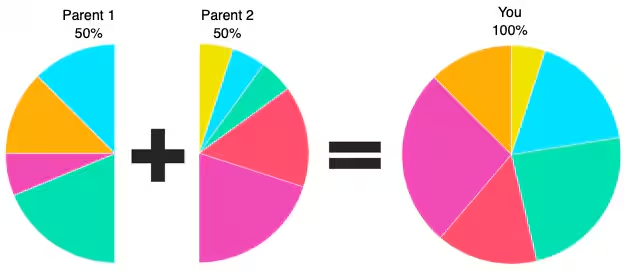

This may look like one custom service among many available online. But its particular proposal—to enable a user to listen to their DNA—is built on an unruly stack of assumptions. At the most fundamental level, there is the question of what kind of cultural information DNA actually contains, and whether one's affinities can be molecularized after this fashion. It's hardly the case that one could be 39% English, 21% Native American, 9% Russian, and so on, or that these separate percentiles of ethnic belonging would make up a full human being; rather, the common culture designated by each of these national terms is imputed an historical individual in their entirety and contemporaneity alike. Our cultural predilections are not guided from within by an inherited code; though one might also ask how the increasingly opaque practice of consumer streaming authorizes this premise. While Ancestry.com has clarified that all information about one’s ancestry must be manually entered into Spotify, and that none of a user’s DNA data is shared across platforms, everything in their marketing is intended to suggest a direct link between genetic code and canny algorithm.

What gives music special purchase on the genetic imagination? To start, there may be no human behavior as general as the appreciation, and creation, of music. This practice, of the organization and sharing of sound, is intrinsically social, fusing cultural groups and groups within groups, across virtually every society on earth. While not every culture marks something called “music” apart from daily life as a separate sphere of activity, let alone as a discrete commodity, it appears to be something that “we” as people do.

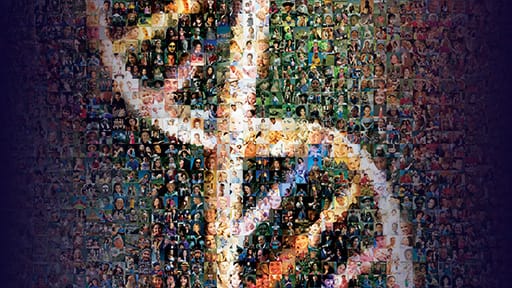

This generality is less comforting against the backdrop of big data, and the fabric of monopolistic services that we use online everyday. In this landscape, all expressive activity is mined for private gain—or more nefarious purposes. In an alarming turn, it seems that Ancestry.com’s pairing with Spotify is their least alarming partnership of the summer. In July 2018, Vice reported that information gathered by DNA websites was being used by the Canadian Border Services Agency to facilitate deportations. Spotify, too, collects immense amounts of demographic data from its 15 million subscribers, and the pairing of these data-extractive behemoths suggests a dystopic near-future of integrated consumer surveillance.

However innocuously, the Spotify and Ancestry partnership proposes to entertain users based on the narrowest possible conception of who they are; and even a gimmicky partnership such as this shows how far this kind of program could extend. Spotify describes this service as “DNA curation,” as though genetic code itself were responsible for the output—unscientific spin that covertly naturalizes the automatizing conditions of online listenership, where people are received as only so many clusters of information.

Between 1990 and 2003, the Human Genome Project made enormous strides towards its goal of a fully sequenced database of all human DNA. By the time of its completion, the international collaboration had accounted for over 90% of the human genome, as well as an informal summit for a range of genetic determinists, seeking a master key for all kinds of human behaviour. In their book Genes, Cells, and Brains, Hilary Rose and Steven Rose offer a social history of the creation of this institution, at an otherwise unprecedented moment of capitalist globalization. At the outset of this project, geneticist Walter Gilbert pulled the sort of cheap publicity stunt to which an Information Age audience is well accustomed—before a captive audience, he produced a single naked compact disc, announcing: “soon I will be able to say ‘here is a human being; it’s me.’”

This gimmick was often repeated as biologists canvassed auditoriums around the world for popular and monetary support. The CD was at this point a token of consumer utopia, and the implicit promise of the symbol was inescapably shaped by its friendliest guise, as a medium of entertainment. For my part, I still recall the spindles of copied CDs that I collected during the early days of music downloading, a relatively unregulated prelude to today’s streaming services, and the open potential of each separate disc. These were receptacles of sentiment; that said, Gilbert wasn’t yet promising his financiers a customizable soundtrack, but something apparently related: a completed account of the listener themselves.

Rose and Rose, however, have serious doubts as to the impressive claims of contemporary biotechnology. “Genetics,” they write, “with benign intent if not benign consequences, has sought to re-racialise human difference.” No research program is ideologically neutral, and the life sciences in particular have been transformed into vast, integrated monopolies over information, “blurring the boundaries between science and technology, universities, entrepreneurial biotech companies and the major pharmaceutical companies.” In this account, the dream of a centralized genetic databank was latently eugenicist from the start: early proponents fixated on the possible elimination of hereditary diseases, for example, and with them a significant cost to society. As usual, these enthusiasts did not seem to consider the bearers of those risks as members of society themselves.

While Rose and Rose hold out for more nuanced attempts to chart geographical ancestry, these goals remain largely unfulfilled by private services such as Ancestry.com. At present, genealogy services advertise the ability to discover one's essence across time, anachronistically assigning national coordinates to considerably more distant and disinterested information. But enzymes have no country, and they certainly do not have national customs. Whatever it might mean to test 17% Norwegian, for example, would depend entirely on a social and historical narrative imposed on that information after the fact; such a test result would not ensure a fondness for either old Norse sagas or second wave black metal, though it could facilitate a contrived appointment with either tradition.

Shortly after the launch of the Human Genome Project, a group of scientists based out of Stanford University initiated the similarly named Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP), with the stated goal of understanding evolution and migration. Proposed by geneticist Luigi Cavalli-Sforza, the HGDP rejected the language of race in favour of an analysis of “population,” gifting future resources like Ancestry.com a more humanistic language and mandate. The HGDP, however, would soon encounter serious methodological controversies of its own. While recording the genetic profiles of Indigenous populations, its researchers repeatedly failed to obtain consent, repeating a long dynamic of colonial plunder.

In her 2013 book, Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science, anthropologist Kim TallBear considers “the implications for tribes of mapping of the human genome.” Skeptical of any approach that draws emphasis away from lived relationships, TallBear surveys a number of problems that arise from the intrusion of genetic science into tribal enrolment. In North America, this appears as a recolonizing vogue for sourcing “Native American DNA” in order to establish descendancy and title. Often, TallBear finds, the application of genetic criteria would prohibit Indigenous nations from determining their own membership and governance, substituting an external scientific standard for cultural participation. As in many other cases where a genetic record takes precedence over the practice of a community, this credits a fantasy of belonging with some immediate material basis outside of history. How many non-Indigenous people have claimed to have “native blood,” a morbid substitute for full-bodied social being?

Sites like Ancestry.com exploit this dream of an unmediated authenticity, where unaccountable scraps of information can satisfy a user's feeling of lack—specifically, the desperation of an individual to be redefined as already including the otherness that their identity omits. This isn't to deny the interest or utility of parsing one’s family tree, nor the value of any historical sense it provides. But these databases enable a kind of genetic tourism, with more sordid implications. Bluntly, race remains the fantasy object of pop genealogy. And however disreputable, race is the concept popularly thought to account for variability and identity, character and culture; thus race is retained within the ideology of genetics as the persistent obstacle it seeks, and fails, to overcome.

This contradiction describes liberal inclusivity, which preserves the categories of identity it would deny by advocating for their inevitable “mixing.” The idea is already incoherent, TallBear notes, given that “mixing is predicated on the notion of purity.” In their landmark anthology Racecraft, Karen and Barbara Fields describe this particular fallacy as “the move, by definition, from the concept ‘mixture’ to the false inference that unmixed components exist, which cannot be disproved by observation and experience because it does not arise from them.” This fallacy is vividly illustrated in the pie charts offered by Ancestry.com and their competitors, which break a test subject’s identity down into contrasting quotients of ethnic belonging. As Fields and Fields describe, race is retained in today’s biology after the fashion of the HGDP’s Cavalli-Sforza, as a “statistically defined population.” The determinations of these populations are not visible, but that hasn’t stopped countless researchers from superimposing racist premises on “post-racial” information sets.

Many proponents of human population genetics reject any accusation of racism, explaining that the scientific methodology offers a convincing argument for anti-racism by simply demonstrating that all humans are of common ancestry. TallBear quotes geneticist and entrepreneur Spencer Wells, whose belief is that racism will eventually abate because it is simply scientifically insupportable. After all, Wells rhapsodizes, “we are all descendants of people who lived in Africa recently. We are all Africans under the skin.” But even this sentiment draws from the history of anti-Black racism for its rhetorical impact, locating an African essence “under the skin,” prior to the social processes that Frantz Fanon referred to as the “epidermalization of inferiority.”

For TallBear, this humanist commonplace is on one hand nonsensical, “given that ‘Africa’ did not exist two hundred thousand years ago.” On the other hand, she continues, following the work of philosopher V.Y. Mudimbe, this anachronistic language speaks of a deep-rooted colonial narrative where “Africa” denotes fantasies of both “difference and primordialism.” In this regard, the statement that “we are all Africans” serves an infantilizing metanarrative, at the same time as it improperly backdates innumerable cultures of which Wells and his ideologues are clearly no part—or so I presume, not having seen their ancestral playlists.

Perhaps it's unsurprising that a genealogy tracker should team up with a music service, because the ideology of genetics is in so many ways a displacement, or anachronistic misplacement, of culture. But the piecemeal essentialism of this creative partnership raises yet another question: to whom does a music belong, and what kind of belonging does it enact? For all that it makes common, the universal power of music does not ensure its global reception, which is secured unevenly at market.

In certain jurisdictions, it’s possible to deal in the redundant catchall of “world music”—an umbrella term used to market the traditional sounds of a geopolitical periphery. This classification originated sometime in the 1980s, a critical decade for the consolidation and expansion of vast interstate systems of political and economic dependency, otherwise known as globalization. World music, then, encapsulates as many musics as enter into market mediation—less a genre of musical production than a condition of consumption. By the same mechanism, music ceases to belong to the world in general when effectively incorporated into the mass culture of an affluent core; and in a circular pattern of influence, musical fusion often projects new versions of the “unmixed elements” it would combine in the first place. For this reason alone it is enormously difficult, and perhaps inadvisable, to talk about the traditional music of any people out of context.

In a now-classic article, “Notes on World Beat,” ethnomusicologist Steven Feld observes another seemingly circular situation: “American music is Africanizing while African music is Afro-Americanizing.” Feld’s key example is Paul Simon’s Graceland, a bestselling album featuring many African musicians. However, Feld insists, "we must scrutinize the nature of Simon’s role from the point of view of the overall ownership of the product (Paul Simon-Graceland, produced by Paul Simon, all songs copyright Paul Simon) and how this ownership maintains a particular distance between his elite art status and the status of the musicians with whom he worked."

On which of Spotify’s themed playlists would a record like Graceland appear? As Feld points out, the appearance of a culturally omnivorous mainstream is ironic in an age of monopoly, where “worldwide media contact, amalgamation of the music industry toward world record sales domination by three enormous companies, and extensive copyright controls by a few Western countries” exert a “riveting effect” on musical ownership. This was already true in 1988, and thirty years later, even after the supposed collapse of the recording industry, the same three companies—Universal, Sony, and Warner—remain among the few financial beneficiaries of centralized music streaming, which has a notably impoverishing effect on artists of any nationality.

If the branding of "world music" in the 1980s stood in contradictory relation to the networks of its distribution, this tension is only heightened today, where a global panoply of musics are appropriated to streaming services like Spotify or Apple Music—digital megastructures whose consumer directive is not so different from that of Ancestry.com: you pay us to show you who you already are. In a sense, the riveting effect that Feld describes applies more to consumers than artists in the present day. Even so, the almost meaningless category of “world music”—an expression of generic otherness, facilitating a pilgrimage of connoisseurship—may help to shed some light on the peculiar desire that Spotify directs in its partnership with Ancestry.com.

In a telling sound bite, Ancestry.com vice president Vineet Mehra gives a straightforward statement of intent: “How do we help people experience their culture and not just read about it? Music seemed like an obvious way to do that.” In this clearly backwards account, culture must be administered in order to be experienced. Mehra’s ideal consumer has a culture, which they are apparently yet to have experienced; so Spotify’s collections of music from different national territories will allow them to participate in this heritage, in the passive reception of a product. This proprietary conception of culture, as mere information, is well suited to the popular ideology of genetics, which offers a vision of human beings as racial metadata from time immemorial.

Walter Gilbert may have tempted skeptics with the promise of a completed human on a compact disc, but fortunately no such object, or playlist for that matter, can encapsulate the complexity and variability of a person. Within its proper jurisdiction, human population genetics tells us many fascinating stories. But genetic data is not itself narrative, and stories are not that kind of object. They travel through and across kinship relations, in spheres of community.

In one of the more personal essays in Racecraft, Karen Fields describes an ethnographic journey undertaken with her grandmother, whose oral history unfurls a detailed litany of people and places. According to Fields, this intrafamilial, and interpersonal, approach specifically refutes the molecular and ahistorical tack of the DNA test and its promise of a technologically verifiable ancestral ground. “Personal Genetic Histories deploy scientific techniques that purport to enable clients to ‘recover’ lost aspects of their individual ‘history,’” she writes. "Quite different techniques deploy the actual memory of individuals to reconstruct a collective history." To this end, Fields counsels to start with “what one cannot remember mistakenly,” a suggestive formula for work performed alongside one's living ancestors; an intergenerational undertaking with its own personal soundtrack.

At its best, music is often accompanied by a feeling of deep physical agreement, which makes it a uniquely convincing vehicle for any story of origins. All music is the music of others, after all. But this doesn’t mean that the arena of musical reception is a frictionless utopia of information. Artist and writer Jace Clayton, also known as DJ /rupture, prefaces his book Uproot with a remark on the twenty-first century as a time of “great forgetting”:

As so many of our ways of communicating with each other and experiencing the world translate to the digital and dematerialize, much is lost, and many new possibilities emerge. When people look back a hundred years from now, this time will be seen as a crucial turning point, when we went from analog to digital. Much of what is special about this transition gets articulated by music, those waves of magic that happen when the human spirit joins with technology to create vibrations that enchant us regardless of language or age, afloat between novelty and tradition and always asking to be shared.

Today, as digital monopolies consolidate their hold on the whole of human culture, restricting rather than expanding the possibilities afforded every user, we're still able to decide what to defend and to forget. At such a turning point as Clayton names—somewhere between sheer novelty and flimsier tradition, deep experiment and diligent identity—it's worth fighting for technologies that don’t seek to exploit the very cause they claim to represent. As quickly as big tech has infiltrated our most personal expression, we can start to change course.

Select Cancel plan; continue through to confirmation message.

Close the tab and pay a band.