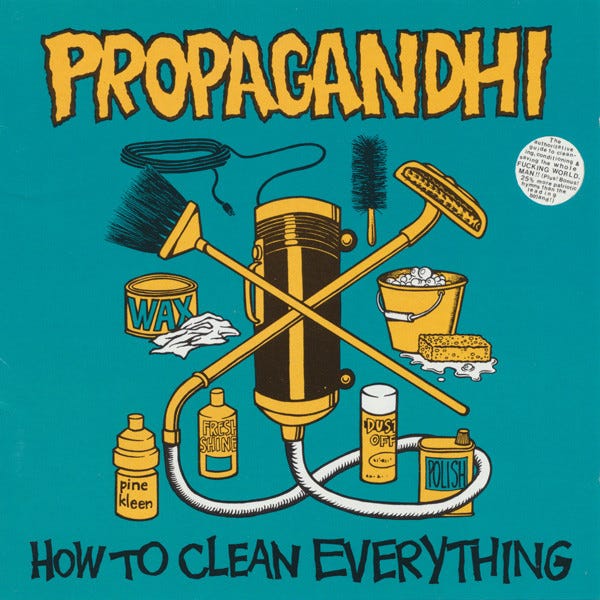

How to Clean Everything

Or, the Importance of Being Earnest

Just over thirty years ago, Fat Wreck Chords released How to Clean Everything, the debut album by Winnipeg-based punk band Propagandhi. Growing up in Canada in the nineties, this record was ubiquitous; coming up in punk more generally, it was divisive. Today, it is that funny, formative thing for so many fellow travellers—a cringeworthy classic, and a shaky start to one of the truly progressive arcs in punk.

“I have come believe that there is value in having something that haunts you until you are dead,” singer and guitarist Chris Hannah wrote on the 20th anniversary of How to Clean Everything. Ten years later, he’s no more kindly disposed to the album. “That’s fucking terrible, what kind of a fucking idiot would like that?” Hannah proclaimed in a video posted to the band’s Instagram account on May 31st, its official birthday. Elsewhere, in a more generous mood, Hannah addresses the record’s posterity:

I dig it. We still play songs from that record. When I hear them and I play them, the message still resonates with me and I can see the 20 year old Chris writing those songs …I just don’t like when I hear that record, like when I hear that actual record, that recording. That moment in time. I’m just like, "Jesus Christ, turn that fucking thing off."

How to Clean Everything is a time capsule in every respect. Most obviously, it is a point for point instructional in the prevailing skate punk sound of the early nineties; a suburban house style preserved on dozens of coaster-sized compilation CDs, spanning third-wave ska and frequently lecherous pop punk. Founded in 1990 at the cusp of this explosion, Fat Wreck Chords would become the main vendor of this sound, which was in large part influenced by co-founder Fat Mike’s outfit, NOFX.

Coming out of the California skate rock scene of the eighties and the rigidly uptempo milieu of Mystic Records, NOFX consolidated the sound of a decade, combining the palm-muted speed picking and galloping rhythms of heavy metal with the incessant upstroke of third-wave ska; nasal harmonies with adolescent humour. This template describes the young Propagandhi, too, who met NOFX at the oft-romanticized Royal Albert Arms in Winnipeg. Impressed by their performance, Fat Mike offered to put out an album on his then-fledgling label, even flying the band to California to record over six frantic days. The end result would have Fat Mike’s fingerprints all over it, stylistically aligned with NOFX’s comedic frat-rock whilst bristling at its stated and unspoken values. Hand-biting contrariety was what Mike paid for, however, and the hastily assembled LP would soon become one of the best-selling punk records of the decade.

For all the trappings of its age, the significance of How to Clean Everything is largely sociological, where the band’s political agenda was so loudly signposted as to become a site of resistance and recruitment for thousands of fans. “Animal-Friendly, Anti-Fascist, Gay-Positive, Pro-Feminist,” proclaims the label on their second album, facetiously entitled Less Talk, More Rock; which only doubles down on the sermonizing strewn throughout their debut. Propagandhi might have blended in with scores of other early nineties pop punk bands in style—to be fair, they’re a lot better for their early and implicit interest in thrash metal—but they stood out for their hectoring insistence on a range of social justice issues, and the relatable, if often wincing, naïveté with which they voiced these moral epiphanies. “But wait a minute, Dad,” Hannah sneers mid-record: “did you actually say freedom?” Today this unfilial speech is nearly unlistenable to my ears, but you have to appreciate just how many family dinners were ruined by this record’s example.

I came upon punk rock slightly later than the era of How to Clean Everything, when a covertly encouraging junior high school teacher loaned me a tape of Less Talk, More Rock in the seventh grade. Less Talk, More Rock is the more accomplished record by far, honing the template of How to Clean Everything in the direction of thrash rather than pre-chewed bubblegum. To this day the recording sounds great, massive and clear, and the message is more than respectable for all of its targeted pedantry. Bright and sanctimonious, faster than the fastest music I’d yet heard, I was both hooked and chastened. I became vegetarian within a year, vegan inside of two, and by the time I reached high school I was sure that I knew more about US foreign policy than anybody in my suburb. Repellant, I know, but well-meaning.

At the outset of an earnest decade, Propagandhi would attract the ire and admiration of countless people trying to make sense of their place in an unjust system. These relatively privileged epiphanies—interpellating their listenership as ignorant in order to deliver a teachable moment—haven’t aged so well, because they probably weren’t intended to travel the world as they did. This is a first record that is also a record of firsts, and its exhilaration is inseparable from the feeling of righteous discovery that accompanies punk in all eras and variations. The tone is grating, self-reflexive and accusatory at turns: “But I will remain until this self-awareness fades; until I defeat the purpose of this soapbox that you made,” the band proclaims on ‘Anti-Manifesto,’ the album’s opener and likely high-point. After a hasty overture, the guitar breaks into oblique ska rhythm, a squeaky chord melody immediately recognizable to forty-something skaters everywhere. The song ends with three-part vocal harmonies before an exultant lead, colouring the typical single-note pop punk solo with subtle sweeps and hints of NWOBHM flair. Even today, it’s a serious good time.

As for the record as a whole, there’s probably a serviceable five-song EP of petulant pop-thrash somewhere in there; beyond which there’s also a wastefully ironic Cheap Trick cover, in keeping with a nineties penchant for unrequested pop hits; a reggae sing-along that confusingly conflates Rastafarianism, a religious and Black nationalist movement, with political Zionism; and the aggressively unfunny parody ‘Ska Sucks,’ which disavows the dorky pleasure it enacts. These are at least as problematic as a certain Smith’s insistence that “reggae is vile” or the early punk adage that “disco sucks,” but have largely escaped scrutiny for the good reason that they are essentially juvenilia. In fairness, the band has dropped the reference to Rastafari from recent sets in which they specifically call out New Atheism instead. Furthermore, these idiomatic gestures are reconstructed on the band’s true opus, Today’s Empires, Tomorrow’s Ashes, where a Judas Priest quotation precedes a brooding, bass-heavy reggae outro within the span of a minute, and neither is played for laughs. (‘With Friends Like These, Who the Fuck Needs Cointelpro?’)

This comparison might seem unfair were it not encouraged by the band’s own musical growth. Since Today’s Empires, and with the addition of bassist Todd Kowalski from melodic hardcore band I-Spy, Propagandhi have created one of the most elaborately composed and thoughtful catalogues in punk, or anywhere. Today’s Empires opens with the song ‘Mate Ka Moris Ukun Rasik An,’ contrasting the singer’s life in an imperialist enclave of luxury with that of East Timorese activist and refugee Bella Gahlos:

I’m still humbled by it all: around the same time that I was riding with no hands, busting windows and getting busy behind the sportsplex (with Labonte’s older sister decked out in her Speedos), Bella was flinching from the sting of a Depo Proveran “family planning,” her own Pearl Harbour and a holocaust spanning 25 years to the rest of her life.

Here the band’s lyrical trademarks—prolixity, compunction, self-disparagement—compose an intricately enjambed personal essay of international scope. Melancholic chord voicings and flurried arpeggios counterpose an independent, snaking bass before the song accelerates, recalling the progressive atmospherics of Megadeth or Voivod more than the Californian cock-rock sedimented into skate punk convention. This era’s signal anthem follows quickly: ‘Fuck the Border’ was an I-Spy song, with a harried chorus at a clip, before the band transformed it into a swaggering, Cro-Magnon cri de coeur and live staple.

Today’s Empires would commence a five-album streak of methodical, progressive thrash; and I remember waiting for this record to drop during the group’s prolonged hiatus from local gigs, undertaken to discourage the anti-social extremes of behaviour that would converge at shows: “Play-acting ‘anarchists’ and Mommy's-little-skinheads.” These were the poles of the punk scene as I encountered it—murderous louts and their pale imitators on one hand, and painfully correct, often humourless, hippie punks on the other. And while the embittered, internecine social detail of Today’s Empires was lost on me in many particulars, theirs was a steadying voice in those confusing years.

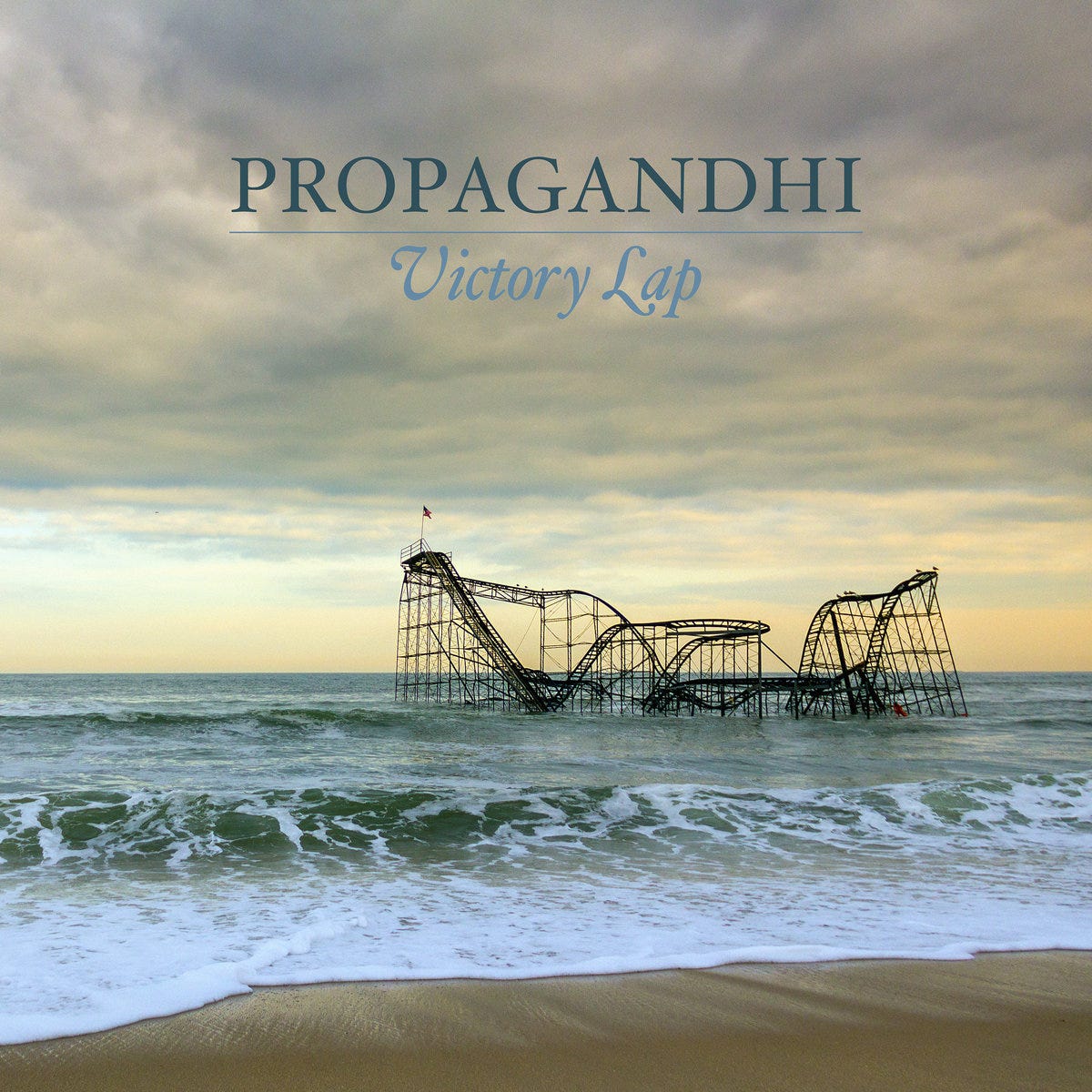

Since then, I’ve grown with rather than apart from Propagandhi, making them that rare thing—a childhood touchstone that evolves with the listener. Their most recent album, Victory Lap, is a meta-commentary on the places they’ve been and substantially new—‘Negrido’ continues Todd Kowalski’s starkly realist catalogue-within-a-catalogue, one of my favourite bodies of song anywhere, and Hannah annotates their greatest hits with wit and bitterness on the butt-rocking ‘Tartuffe,’ before the existential prog-essay ‘Adventures in Zoochosis’ concludes a searing, searching program.

It’s far more common to grow out of punk than to age inside of it, and the cloying nostalgia of ex-pats doesn’t leave a lot of space for a fair assessment of the bittersweet stupidities and righteous surety associated with the flush of youth. It’s harder still to hold to the truth of youthful indignation whilst developing that glimmer of initial insight, or to wince and reminisce at once; protecting all the moments and their causes that felt so significant back then.

As always, there’s no accounting for taste; but Propagandhi are a model of (cringing) accountability for where they’ve been, in honour of all that their music has meant to so many listeners over the years. For all of its pranks and discomforts, How to Clean Everything begins that journey. It’s the worst album, even a bad album, by one of my favourite bands, and I’m just so grateful it exists.