In Order to Survive

A Statement

In August 1984 in the United States of America, revolution was nowhere in sight. In Lawrence, Massachusetts—the first planned industrial city in the country—white residents lashed out against their Latino neighbours, precipitating a days-long race riot. Throughout the Southern states, the NAACP picketed dozens of grocery stores operated by the Food Lion monopoly after the company walked out on negotiations to improve employment rates of Black workers. Ronald Reagan joked on a hot mic that he had "outlawed Russia forever," and that the US would "begin bombing in five minutes." Weeks later he would receive the Republican nomination, paving the way to his second term in office. (The current administration, one could say, marks his eleventh.)

In New York City, gentrification showed its teeth, following the near-bankruptcy and dereliction of the preceding decade. In 1984, the city initiated a network of "Business Improvement Districts," now a staple jurisdiction of any capitalist civic, beginning with Union Square; and while such an authority wouldn't officially preside over parts of Lower Manhattan until the early nineties, the radial effects of this turn to essentially private governance were quickly felt throughout the city. On the Lower East Side, where bassist and composer William Parker had lived since 1975, the speculators were encroaching. Over two years, average rents had gone up 400 to 800 per cent.

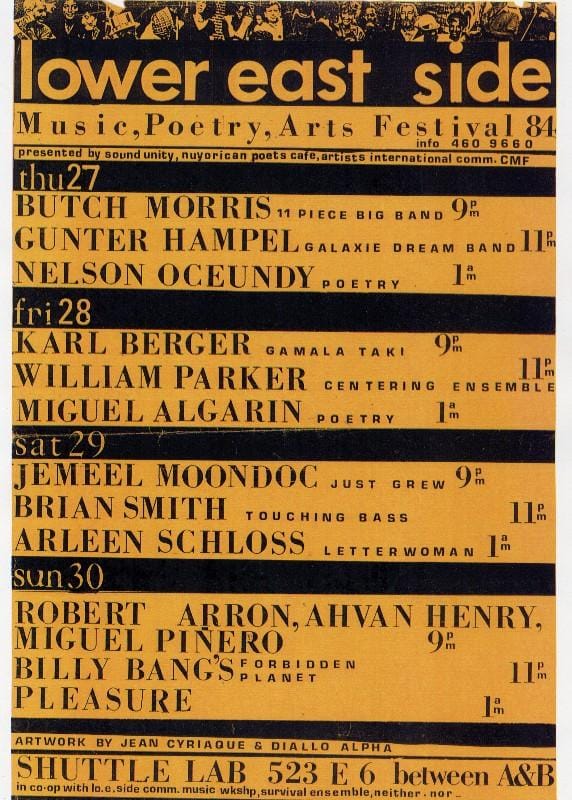

Even so, low-income and longtime tenants remained; and artist-residents continued to hold ground. The Nuyorican Poets Café, founded in 1973, had purchased a tenement building at 236 East 3rd Street in 1981; and in June 1984, Sandro Dernini of Plexus International would open the Shuttle Theatre at 523 East 6th Street, between Avenues A and B. Plexus gathered an unmarketable counter-current to the commercial traffic in "East Village" art and artists, specializing in less readily alienable, more obviously social media, like music and food. These gregarious performance rites have all but eluded record, as Stephen DiLauro notes; but in the eighties, Plexus furnished space to a large avant-garde increasingly sidelined in the improvising city it so aptly expressed.

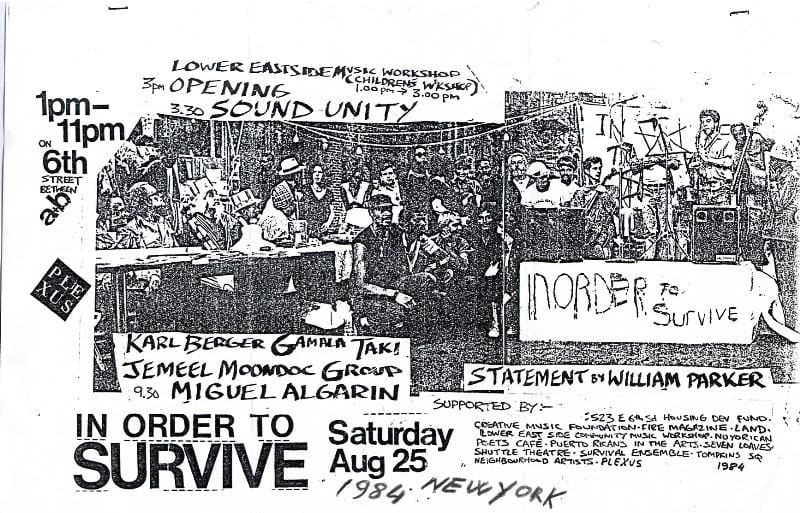

It was here, outside the Shuttle Theatre on August 25th, that William Parker stood and delivered one of the most politically cogent and far-seeing texts of a demoralizing era. "In Order to Survive: A Statement" would not only contextualize the day's main event, a block party to oppose the gentrification of the Lower East Side—it would name Parker's next working ensemble, whose music continues the spirit of this written intervention today. The text is remarkable enough to quote in full:

In Order to Survive: A Statement

We cannot separate the starving child from the starving musician, both things are caused by the same things, capitalism, racism, and the putting of military spending ahead of human rights. The situation of the artist is a reflection of America's whole attitude towards life and creativity. There was a period during the 1960s in which John Coltrane, Malcolm X, Duke Ellington, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Bill Dixon, Sun Ra, Martin Luther King, and Albert Ayler were all alive and active. Avant-garde jazz contemporary improvised music coming out of the Afro-American was at a peak of creativity and motion.

ABC Impulse was recording Coltrane and Archie Shepp, ESP Disk was recording the music of Albert Ayler, Sunny Murray, Sonny Simmons, Giuseppi Logan, Noah Howard, Frank Wright, Marion Brown, Henry Grimes, Alan Silva, and many other exponents of the music. Blue Note and Prestige Records were recording Andrew Hill, Eric Dolphy, Sam Rivers, Ornette Coleman, and Don Cherry among others. Radio stations such as WLIB, now called BLS, and WRVR, which now plays pop music, were both playing jazz 24 hours a day, including some of the new music of Coltrane, Shepp, Ayler, and Ornette Coleman. There was energy in the air as people marched and protested in the north and south demanding human rights, demanding that the senseless killing in Vietnam stop.

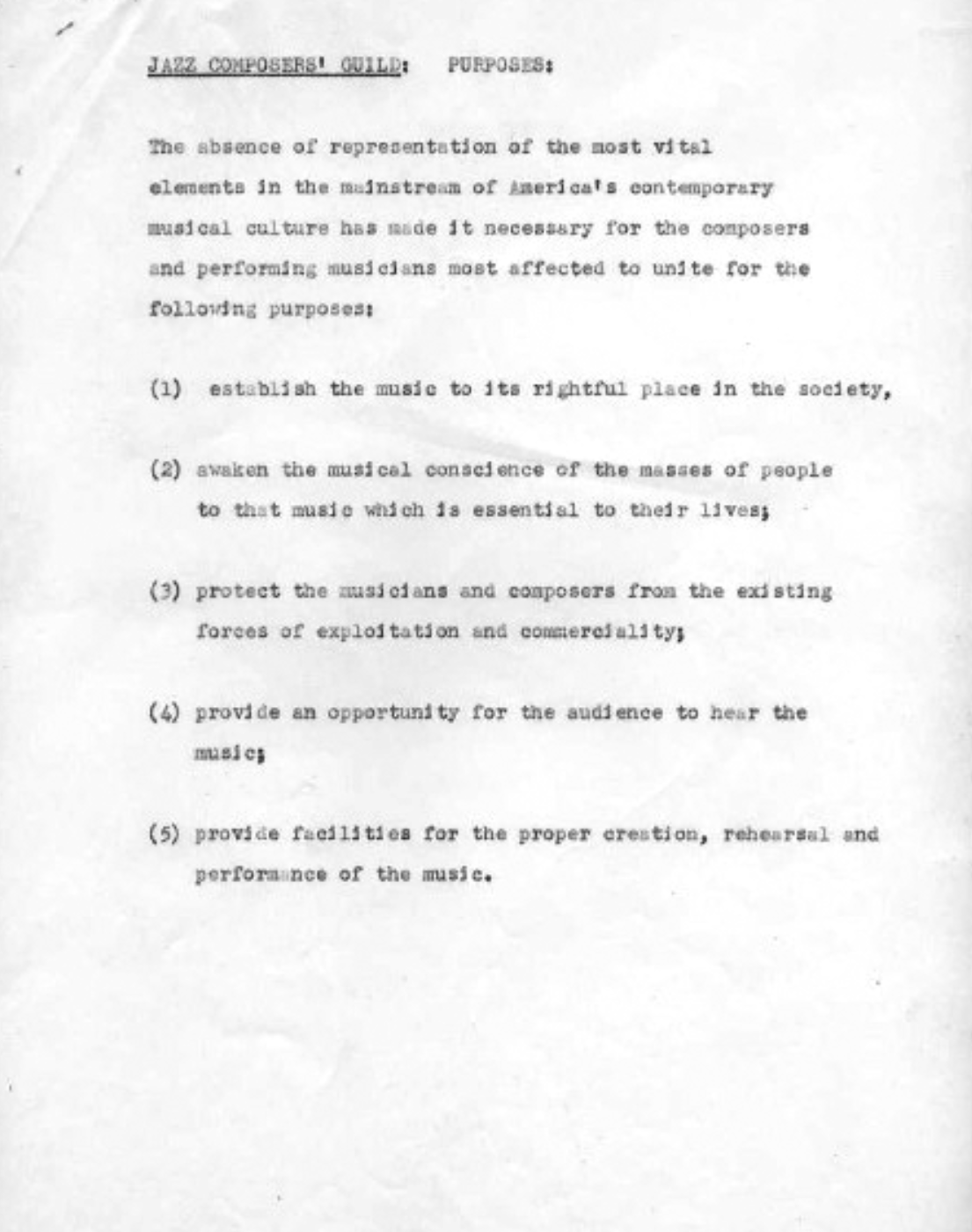

Simultaneously, like musicians before them, the avant-garde became aware of the necessity to break away from traditional business practices. Like musicians' lives being in the hand of producers and nightclub owners who only wish to make money and exploit the musician. The musicians began to produce their own concerts and put out their own records in order to gain more control over their lives. The Jazz Composers Guild, formed by Bill Dixon, was one of the first musicians' organizations in the 1960s to deal with the self-determination of the artist. Other efforts had been made by Charles Mingus and Sun Ra as they both had produced their own concerts and records in the 1960s. To follow was the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians) formed about a year after the Jazz Composers Guild, and Milford Graves, Don Pullen, and the record company SRP (Self Reliance Program).

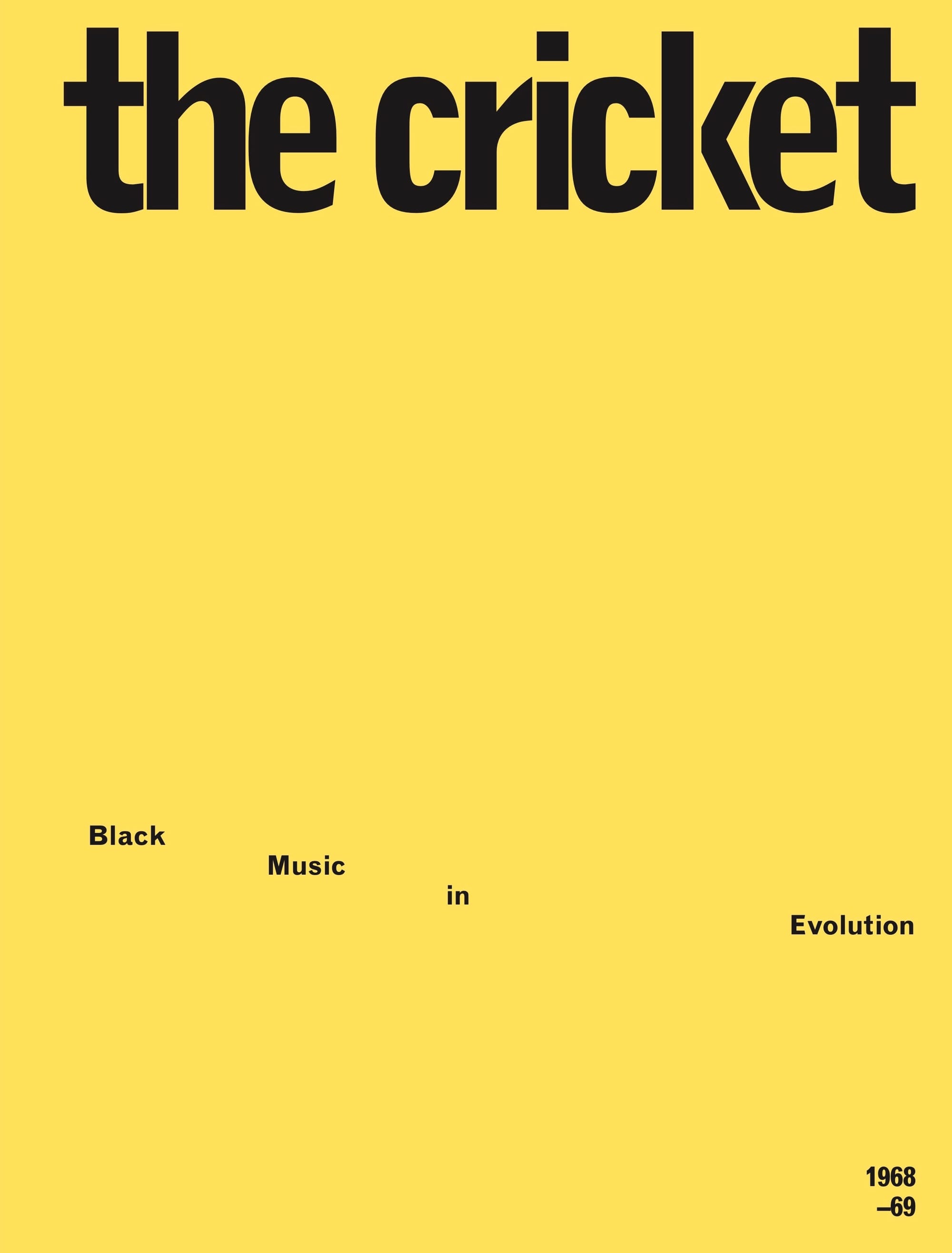

Musicians got together with poets to put out a magazine called The Cricket, and all the articles were written by poets and musicians themselves. It was edited by Imanu Baraka, Larry Neal, and A.B. Spellman; advisors on the magazine were Milford Graves, Cecil Taylor, and Sun Ra. Contributors included Roger Riggins, Stanley Crouch, Albert Ayler, and Ishmael Reed. The motto was "Black Music in Evolution."

Just as the music and the movement began to break ground establishing itself, several things happened: Malcolm X was assassinated, Martin Luther King was assassinated, John Coltrane, died, and British rock-and-roll began to change the music industry. Not only could records be sold, they could sell posters, books, wigs, dolls, and thousands of electric guitars to the youth of America. They promoted and pushed rock music as the real thing, yet when these rock stars were interviewed they would always cite jazz or blues as the origin of rock. Also at this time there was a sudden increase in the availability of drugs in the black community. Every apparent gain as a result of the civil-rights movement was not given up without fight. All gains were achieved because America had a gun to its head. To question, to speak of change, was never willingly allowed, but the 1960s movement was so strong that it couldn't be denied. They could silence a few poets but they couldn't silence an entire nation.

The 1970s was a period of tranquilization. There was no mass movement to continue the motion set forth by the 1960s, it was a ten-year period of systematically silencing and discouraging the truth. Poets were made to feel like criminals; people were going back in time because it seemed easier than going forward. Record companies began only to record safe music, musicians began to water down their music. The C.I.A. and F.B.I. had files on the music—and those whose politics were considered a threat to the existing inertia. The neglect of the poor, the neglect of the arts is no accident, this country is sustained by killing off all that is beautiful, that deals with reality. They will go to any lengths to hold back the truth, to prevent the individual from hearing and seeing his or her own vision of life. Some people are controlled by neglect, while others are controlled by making them stars.

As the 1980s arrived this fire music that talked about revolution and healing had almost vanished—only a few musicians continued to play and develop it. The sleepiness of the 1970s gave birth to a new electronic age of computers and video machines. Wherever human energy could be saved, it was popular music that lost what little identity it had. In listening to today's pop music it's hard to tell whether the group is male or female, black or white. Synthesizers have replaced living musicians. We have all been desensitized. People walk around in a daze sitting back while these blood-thirsty gangsters have free reign of the country and of the people's lives.

Our food sources, our housing sources, are owned and operated by power-hungry people who do not have our best interest in mind, they only wish to make a profit. All of this is not new knowledge, it has been said many times before, the message must be constantly repeated, intellectual knowledge of the problems is not enough, we must feel the blade piercing the hearts of all who are oppressed, jailed, starved, and murdered by these criminals who call themselves leaders who act in the name of peace and democracy.

Since we have little we must band together pooling all our little resources to form a base in which to work. We must learn from all the mistakes of the past, dropping any selfish notions in order for this movement to succeed, in order for it to take root and begin to grow. We must ask the questions: Why am I an artist? Why do I play music? What is the ultimate goal? Am I playing with the same spirit that I played with 10 years ago, or have I just become more technically proficient?

The idea is to cultivate an audience by performing as much as possible on a continuous basis, not waiting to be offered work, rather creating work. Uniting with all those who hear. Those who are willing to go all the way. We must put pressure on those with power to give some of it up (picketing, boycotts, petitions, whatever it takes), and finally we must define ourselves and not be defined by others. We must take control of our lives, building a solid foundation for the future.

From the opening provocation, Parker makes it clear that any musical striving must also be for social advancement in general, or it is worth nothing. All that is necessary for the musician to survive is necessary for the child, and neither designation operates a special interest. This thesis alone refutes a lot of merely vocational activism of the moment, in which I can think of several lauded attempts to re-brand fairly traditional and inaccessible granting structures as a "basic income for artists," getting an alright idea all wrong. In the case of these few pilot programs, art is preserved as a calling apart from its society, rather than a general activity of which anyone ought to be able to partake. This limited advocacy for artists doesn't challenge the ownership of means, nor does it address the artist as a general being.

Parker refutes this artificial and aristocratic separation. The artist is not a special interest, but a common recipient of the conditions faced by their community; which can then be measured by the welfare of the artist. This mutual accountability, verging on identity, of interests drives Parker's program, with ample precedent in the holistic musical cultures of the sixties avant-garde. Rather than settle for dependency, Parker invokes the past organizing of working musicians, with special attention to the free jazz era; in which focus shifted from the "trade-union consciousness" of earlier generations, defending performance as a site of labour, to the autonomous conception of the Black Arts Movement and its fellow travellers, centring music as a means of cultural production or nation-craft.

Parker's list of social innovators affirms as much; where "the music" and "the movement" proceed in lockstep. From the movement for political and economic self-determination, he explains, artists extrapolated a need for their own independent labels and organizations. Here Parker checks some of the flagship integrities of the sixties; including the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) in Chicago, which continues as a nonprofit today; and the short-lived Jazz Composers' Guild, spawned by the suggestively named "October Revolution in Jazz" concerts at the Cellar Café in 1964.

In his great tome on the culture and formation of the AACM, scholar and composer George E. Lewis places the group's designs on cultural autonomy in the longer context of ancestral displacement and the Great Migration, during which millions of Black Americans sought better fortune and relative freedom in the North. In large cities like Chicago, this movement resulted in the creation of resilient Black cultural infrastructure, more and less formal. This included churches and talent shows, social clubs and mutual aid societies, all of which would influence the scenery and purpose of jazz. Historian Gerald Horne describes how the relative economic influence of Black migrants in this period helped to create a network of theatres and dance halls, which were soon integrated into the underground economies of mob-dominated Chicago. And yet, in spite of the parasitism of organized crime, Chicago soon boasted several times as many amenable clubs as New York City, becoming a national centre of the emerging music.

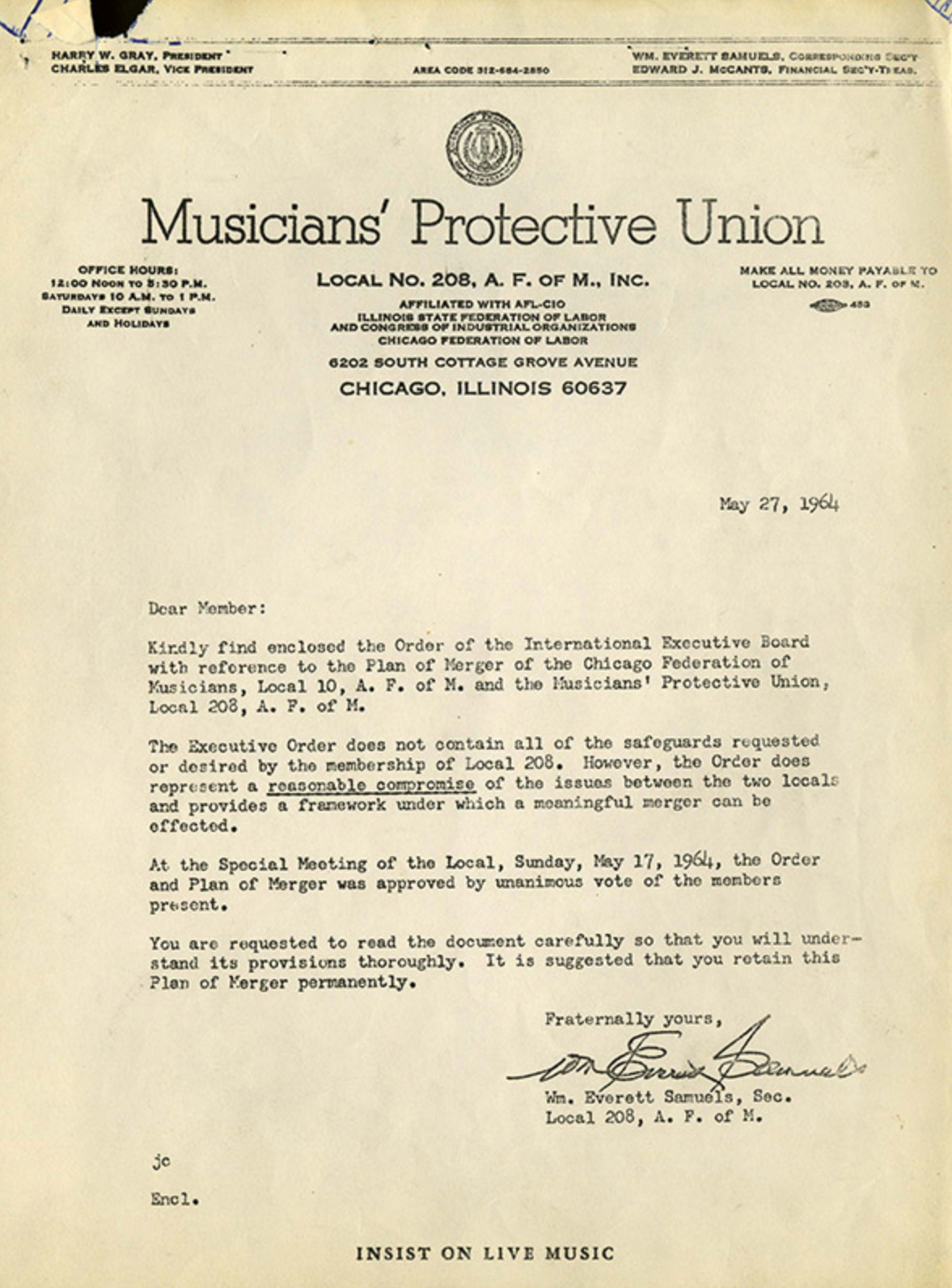

Crucially, AACM founders such as Muhal Richard Abrams were members of Local 208 of the American Federation of Musicians. Founded in 1901, this was the first Black AFM local, and an important place of economic development and creative interchange where the first generation of the AACM would have apprenticed as a matter of course. (Local 208 merged with the majority white Local 10 in 1964.) Following the practical lessons in independence that the city furnished them, the AACM undertook to redefine "the discursive, physical, and economic infrastructures in which their music took place," Lewis writes; playing their own compositions, maintaining their own spaces, and running their own music education programs for community. Today, the AACM remains a gold-standard of artistic advocacy and professional development, synonymous with the highest aspirations of an era.

As scholar Benjamin Piekut describes, the Jazz Composers' Guild in New York was conceived in a slightly more oppositional register, intending to withdraw the labour of its membership from the major clubs and labels. Any work opportunity would be voted on by the Guild, with the goal of involving as many members in accepted gigs as possible. “Our idea is to corner the market, to take this music off the market for as long as is necessary to establish the kind of relations with the business people that are needed to give the music its proper outlets," said Bill Dixon. "Meanwhile, we’ll generate our own activities."

Radio State - February 26 2024 - The Jazz Composers' Guild

The October Revolution concerts concluded with midnight panel discussions on topics including Jim Crow and the Economics of Jazz, welding public education to performance and creating space for the organic intellectuals of the movement. The performances were well-received and the achievement of Dixon's short-term goals recommended further advocacy; but the Jazz Composers' Guild was not a simple feat to organize. As Piekut relays, several participants objected to the word jazz; some to the word composer; and others to musician-organizer Bill Dixon's unionism by another name—the term 'guild,' with its Fabian associations, barely passed consensus. However well these musicians communicated in their common medium, a shared political understanding of their collective situation would prove difficult to achieve.

Even so, the Guild carved out a space for a resolutely non-, even anti-, commercial music, flowing from the practical and theoretical concerns of the players themselves, before imploding after less than a year of work owing to bitter internal tensions. Piekut diagnoses a cleave between Baraka's pan-African "populism" and Dixon's syndicalism, which maps onto a schematic distinction between cultural and economistic solutions to the targeted underdevelopment and obscurity of Black arts. No doubt this was a factor, and these apparently divergent programs must be reconciled in Baraka's own work; but Piekut carefully replays the microsocial tensions within the group, refuting a simplistic understanding that it came to pieces over "racial tensions" or professional aspirations. But come apart it did, and quickly; leaving its ambitious designs on political independence to future projects.

The internecine struggles of the Guild are far too complex to reiterate here; but worth mentioning in order to note that something interesting happens by way of historicization in the "sleepy" 1970s and complacent eighties, such that Parker's 1984 cri du coeur can enlist any number of opposing figures in its portrait of a militant era. Naturally, Parker knew these people and their intrigues; he played with many of them, and came up amid their storied context. The editors of The Cricket, for example, which directly inspires Parker's manifesto, were among the strongest opponents of Dixon's leadership at the time of the Jazz Composers' Guild, even singling out his playing for dim appraisal. And yet their causes appear tightly united in Parker's ecumenical assessment of a Black radical sixties.

It's become a sporting subtopic of popular history to debate the specific year in which "the sixties" ended, and by reference to which event. These white-washed histories typically fixate on a youthful, middle-class "counter-culture" headquartered in the United States; or look to massive student movements throughout Europe, rather than the global sequences that inspired them. In many of these accounts, rock and roll scores the decade; but for Parker, the ubiquity of this music and its swelling market share charts a reaction to the revolution underway in creative music, which not only implies a self-determinative cultural expression, but poses a real challenge to commodity logics where its means are predominantly live, collaborative, and non-duplicable.

Clearly the creative period under examination here is not the decade of the Beatles, nor the Rolling Stones. For Parker, a radical sixties ends too soon with the loss of John Coltrane in 1967; and definitively with the death of Albert Ayler in 1970. And though Parker clearly rejects the premise that aesthetics and politics make a parallax view, proposing to perceive both frames at once, one could also use the deaths of Malcolm X in 1965 and Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 to frame a coincident era; the foreclosure of which prompts a shift towards a more militant and political conception of Black power.

In a sense, the decade of innovation that Parker names is staggered with respect to the numerical 1960s, corresponding to the era of the Black Arts Movement and its tributaries. Even so, Parker finds the seventies—the time of his own artistic maturation—to be an era of pacification and dispersion. Government surveillance and narcotic infiltration proceed as if a single program. Poverty deepens while select artists, elevated above and isolated from community by success, are made to stand in for economic development in general. In this description, fame becomes a kind of class collaboration; but in 1984, the market abstentionism that Dixon counselled almost twenty years earlier is more or less assured by contemporary working conditions. No significant labels are cherry-picking artists from the avant-garde, where Parker correctly identifies an inhuman, asocial pop aesthetic as the major adversary of freedom in music. This has never stopped the development of the sound; but as noted above, it has impacted the livelihood, and even threatened the survival, of the practitioners in whom it moves.

To this end, Parker's litany of proper nouns does more than summon an era in overview; these points of cultural reference crystallize a moment or event of significant duration and attendance. Parker's itinerary of Black power in the Reagan eighties makes a fidelitous response to the work of the sixties, keeping its reception open. The roll-call isn't meant to mortalize or foreclose the achievements of the players it enumerates, but to re-establish the present era in sequence of an unfinished revolution. Today, this order would include Parker's own name; as well as Jemeel Moondoc, Billy Bang, Patricia Nicholson, Miguel Algarín, Karl Berger, and other participants in the Lower East Side renaissance that produced In Order to Survive—the event, the statement, and the group.

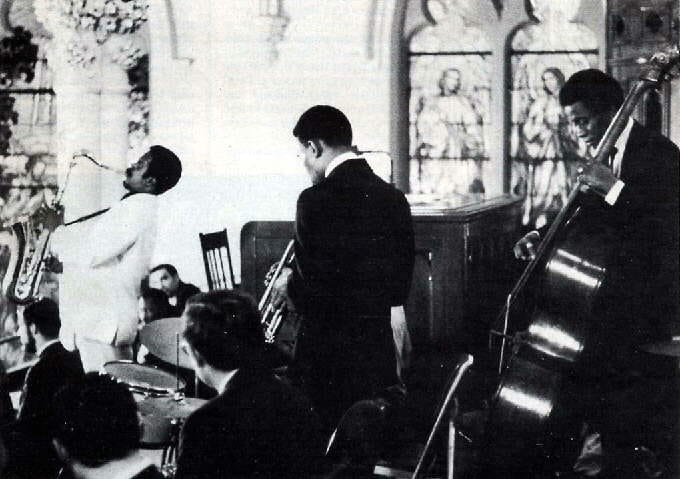

The original "In Order to Survive" concert took place on August 25th 1984 and was organized by Plexus, Nuyorican Poets Café, Sound Unity, Puerto Ricans in the Arts, Local Action for Neighborhood Development (LAND), and other community groups. Sarah Farley, organizer of LAND, co-hosted with writer Bruce Richard Nugent; one of the last living contributors to Fire!!, a crucial document of the Harlem renaissance. A number of artists, including Parker, performed in the street, following a music workshop for local children. Generations convened in defence of their neighbourhood, and of the rights of squatters (or "homesteaders") to the city they'd helped build. It may only have been one of many such events in the life of the neoliberalizing city, but the archival traces of its ceremony give us bearings in a no less precarious age.

Few of the spaces and institutions enrolled in this one fight remain today, but its concerns extend throughout the present; where Parker's call to musicians doubles as a call to organization. In order to survive, the greater artist must become a greater organizer; in which respect Parker even resembles such tendentially opposing figures as both Dixon and Baraka. This inheritance is all but claimed above; and in retrospect of the conflictual sixties, Parker reconciles their respective politics in a broad front project of musician-led community defence.

In his book-length portrait of Parker, historian Cisco Bradley emphasizes the importance of Baraka and The Cricket to Parker's own formation and to the concept of In Order to Survive, as a band and a cultural front. This continuity is moving in itself. In the fourth and final issue of The Cricket, published in 1969 and marking another possible end to the decade, Mtume writes:

The Black musician must, as any other revolutionary artist, be a projector whose message reflects the values of the culture from which his creation owes its existence. He must be the antennae which receives the visions of a better life and time and transmits those visions into concrete realities through the use of sound and substance (each time must be a lecture via entertainment). The Black musician must be both Spiritual, in that he must strive to create visions faster than the present and perpetuate the higher values of man, and Secular in that his music must not go so far out that it transcends the ability of the people to grasp its meaning and message. Therefore the music evolved from the artist would possess simultaneously an aesthetic appreciation as well as a political interpretation of where we are and where we shall be.

This is a remarkable synopsis of the organizational role of the music, and the dialectical relationship between society and spirit, in which the calling of the Black revolutionary musician is akin to Lenin's placement of the party—one step ahead of the class, but no further; mediating the furthest reaching ideals and the present capacity for change, with respect for the origination of these ideas in the practical experience of the people whose lives they would improve. For both Parker and Mtume, 'vision' is the word for this convertibility of art into life; knowledge into understanding; present into future.

Bradley quotes Parker's liner notes to the 1998 album The Peach Orchard: "Vision allows us to experience and live within that endless periphery called poetry. Vision is also the catalyst for human revolution. The response to the cry and the cry itself." In this percipient remark, echoing the insight of an elder era, Parker displays his true strength as a player and an organizer—a gift for listening as one leads, in that order.

Radio State - February 19 2024 (In Order to Survive)

“It is not imperfect/to have died”

It's hard for me to grasp the death of Lyn Hejinian, where her life was made so companionable in writing that it feels a part of ours. I've been re-reading since I heard the news, The Cell, Oxota, underrated texts, and thumbing stacks of Tuumba chapbooks that I scored at Books and Bookshelves on a life-changing pilgrimage.

I wrote about one of her best books, Positions of the Sun, in 2019, and substantially revised this essay for The Vanishing Signs a few years later. Comparing drafts, I only wish that I'd been less intent here to excerpt her from the company of Language writing; for as she herself reminds us, "eruptions of genius (if they exist at all) are never autonomous." But god, I love this work.

Composed between April 2008 and July 2015, the prose poems collected in this book correspond not only to the time of financial crisis but to the seasons of popular protest, insofar as these eruptions correspond inseparably themselves. The poem proceeds against the scenery of a university under an austerity regime, and the activity of the Berkeley Solidarity Alliance, though it is far from straightforward reportage on the excitations of protest. As a work of theory on the social scale of a novel, Positions of the Sun tends closely to the cognitive framework of social experience, and the collective context of cognition, attempting a commensurate poetry.

It's a breathtaking book, blurring dreamwork and the life of the picket; fiercely advocating for, and closely interrogating, the premise of the avant-garde in politics and art alike. "Throughout Positions of the Sun, dream vistas blur with quotidian intrigue; named vectors of mass demonstration and cohabitation extend a discontinuous soliloquy." To read her feels like writing, only better than you ever could—not that there’s any competition where each sentence was a correspondence, which continues. Thank you, Lyn.