In the Red

Max Roach's Christmas, Again

Few figures in the development of jazz are as total as Max Roach. From his first recorded appearances in the 1940s, Roach stayed at the centre of the music in its many changes—originating bebop drum style before embarking on a politically decisive repatriation of the music through Afro-Caribbean soundways, all the while maintaining a presence at the forefront of creative music, as later duos with Archie Shepp, Anthony Braxton, and Cecil Taylor differently attest.

These sessions were never concessions to timely developments, however; by any reasonable standard, Roach himself commits some of the earliest recorded instances of free improvisation, insofar as his prescience obliges us to speak anachronistically. On ‘Percussion Discussion,’ a duet with Charles Mingus from the 1955 album Mingus at the Bohemia, you can hear a whole tradition in wispy silhouette—“avant-garde though I hate the word,” Mingus boasts begrudgingly.

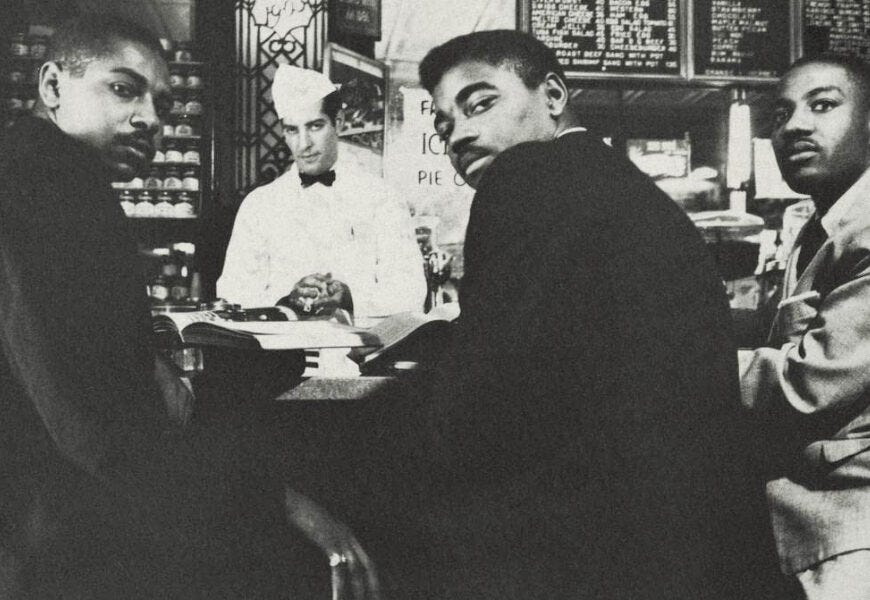

In addition to his farsighted musicality, Roach was politically militant at every moment of his popularity—exploding the parameters of acceptable musical expression in response to unacceptable social conditions. Roach’s 1960 album We Insist!: Max Roach's Freedom Now Suite is a definitive statement of the Civil Rights era, with lyrics by Oscar Brown Jr. and a scalding vocal performance from his future-wife Abbey Lincoln. His composition of the next year, ‘Mendacity,’ serves a brassy, sarcastic attack on racist politicians; ‘South Africa Goddam,’ with Archie Shepp, extends the solidarities of We Insist! alongside the vision of one Nina Simone; and a previous duo commemorates Mao Zedong’s passing at the end of a complex era, demonstrating the significance of his war of liberation to Black radicals in the United States.

As Ed Williams wrote, “Max is a man who knows and understands the importance (influence) of history in day to day living. His thoughts encompass a vast network of ideas, and his perspective for tomorrow is always clear.”

Roach’s 1980s were fascinating too, as preserved on his recordings for the Italian label Soul Note, an affiliate of Black Saint. Take the year 1984: within a span of five days in October, Roach’s percussion ensemble, M’Boom, recorded Collage, containing several masterpieces of mallet-based, multi-rhythmic minimalism; and Roach turned out a lengthy session of contemplative solos, released as Survivors—though the frenzied title track engages a chamber trio, whose hard-angled, sawing unison juxtaposes the extreme fluidity of Roach’s reach. These New York recordings only allude to the riches of an underrated, working decade, but they’re a fine place to start.

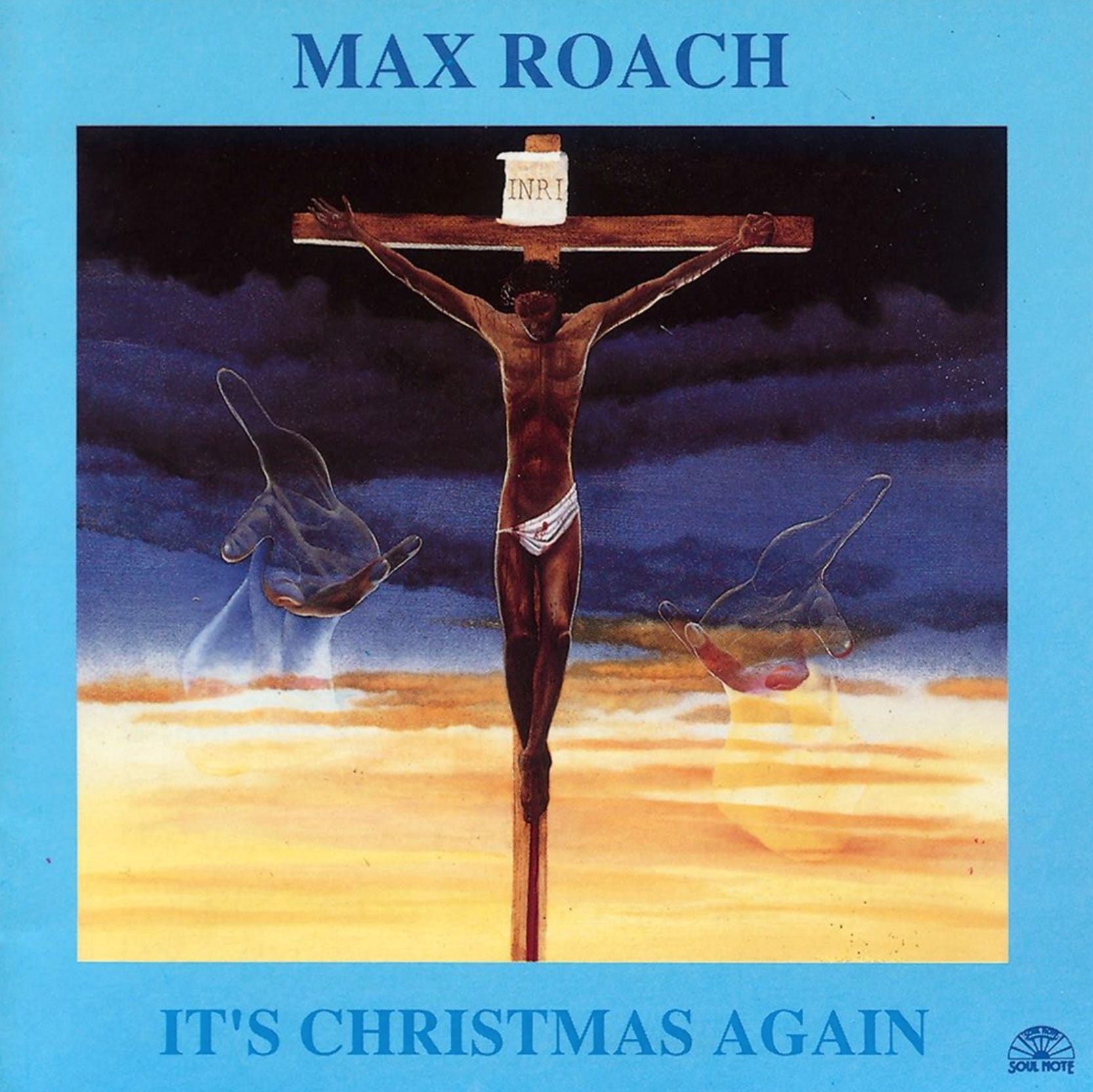

That said, the most interesting sessions of the year likely took place in Milan, Italy that May and June, with the accompaniment of Roach’s working quartet—Odean Pope on tenor saxophone, Cecil Bridgewater on trumpet, and Tyrone Brown on bass. These European dates would eventually yield two albums, Scott Free and It’s Christmas Again. The first, Scott Free, preserves a strong tune of the same name, bookended by a blaring, Coleman-esque theme and moving through a variety of spacious features and subtle grooves.

It’s Christmas Again is something altogether different—a tonally complex holiday diatribe adapted from work by poet and radical jurist Bruce Wright, recorded at the start of summer in a subtropical climate, thousands of miles from the group’s New York City home. These sessions wouldn’t see release for several years, but the title track stands out today as one of Roach’s most prolix, and peculiar, statements—a lengthy, monologic screed against the season, where so many of his generation were long since gone carolling.

Oddly, ‘It’s Christmas Again’ was Roach’s second musical interrogation of the crass commercialism and perfunctory good cheer of the Christian holiday. On ‘In the Red (An X-Mas Carol),’ from the 1966 album Drums Unlimited, Roach solemnly proceeds through a variety of moods, none of them salutary. James Spaulding’s alto solo is strained to despair; and bassist Jymie Merritt leaps and plunges octaves throughout, as if to chart the highs and lows of a difficult season. Nat Hentoff’s liner notes explain:

‘In the Red (An X-Mas Carol)’ is a collage of emotions, some of them ambivalent, about Christmas. There is the red in which Santa Claus dresses. (Or, as Max puts it, “Nobody shoots Santa Claus.”) There is also the economic condition of being in the red as a result of a man’s generosity overshooting his means. “Basically,” Max adds, “the piece will mean different things to different people, depending on their temperament and experiences.”

Of course, the same may be said of any political statement, which will fall differently on different ears depending on class, ideology, and social privilege. Roach’s coy remark knows this, though he appears to accept the role of curmudgeon to a white liberal listenership. By the time of his Soul Note tenure, however, Roach is far less solicitous; and this taste for difficulty results in one of the most complicated emotional arrangements of his career.

‘It’s Christmas Again’ begins in humid apprehension. An erratic, racing woodblock prefaces the group’s arrival, setting an anxious pace against the backdrop of a lush, unseasonable field recording. Backed by a rustle of percussion, blending birdsong, the poem begins:

God burns His words upon our sight

Allows the Middle Ages through long-time minstrels

To sing Trappist lections to communion

While the tears of Christ

Daily irrigate our arid dooms and jokes.

Voices in overlay urge on the monologue (“that’s all right, that’s all right”) as Roach repeats the invocation, savouring each phrase with heavy, shifting emphasis as befits a percussionist’s oratory. A bell tolls in the virtual distance, announcing the quartet’s gradual entry. Brown walks languidly, Bridgewater riffs, and Wright’s poem continues:

If only God’s hand at His easel could compete

With Andrea della Robbia’s angels & Rembrandt’s revelations;

If only the sacred graffiti of His patriarchs could match the writings

Which reek with truth on subway toilet walls (tell it like it is)

But then, had the Gauls not lost their long division to Caesar?

“Oh great Caesar,” Roach repeats facetiously, rendering a minimum of respect for the historical trajectory he names. The studio is an important instrument here, where Roach accompanies himself several times over, even creating clutter. A flurried vibraphone gives way to a descending peal of bells, as if announcing actors in the distant history that Roach rehearses—a litany of conquests lurking in the background of Christian ascendancy. Perhaps because of the session’s Italian setting, our narrator is in an antique frame of mind; drolly annotating religious custom and its supportive landscape as historical contingencies: “And had Hannibal never lost his way with elephants after winning his long hike, the Mediterranean’s melanin would have cast a darker shadow over what the Romans lost.”

Roach’s poem posits this contingency as an impediment to faith, where the very scenery of revelation and its artistic representation are both object and outcome of political contest. Amid an admittedly hazy instrumental weft, elements of musical pastiche extend this commentary: the woodblock counterposes a clip-clopping lope to Roach’s laid-back swing, subtly evoking sonic tropes of the Christmas season. “Brother, will you stand with me?” a further voice sings, stage-right of the central soliloquy, affecting that most dissonant thing—a cynical spiritual jazz.

So let us then on proud occasions pray and ponder as we reach to touch

And feel the unnamed shapes

Moving behind Modigliani’s skies.

Let us welcome every easel’s sweet deception

And then with the deceived mind’s arrogance made securely right

We can mask those matters which we wish not to matter

With fictions of disguise and live again

Through all the empty battles of the past and there ghostly rise and fall.

Brave legions of foot and horse have always ached and ailed in someone’s sleep—

Both in death and in its dust does God’s arithmetic count the losses of his sheep.

It is Christmas again, a time for famous feasts …

By now, the record is becoming crowded; slide-whistles and triangle rolls separate the caustic monologue into a series of cascading punchlines. Between these slapstick effects, Bridgewater’s trumpet maunders thoughtfully as if inside a different timeline. It shouldn’t work so well, but this thematic oversaturation finds its complement in the poem’s closely associative outpouring. Plucking symbols of falsity and subterfuge from a literary reservoir, its vision turns to the commercial tat by which we know the time of year—phantasmagoric forms of an occluded social relation; trinkets of affection addressed as if haunted themselves.

It seems the woods of Birnam have been captured in every room

Where toys spread their mechanical imitation of life

And with the ghosts of broken baubles out of sight

It is time to make children of our minds;

And we sit among the tiny moving figures we have wound

Pursuing a child’s emotion on a wintertime merry-go-round.

The icy pipes skip a note or two in the harsh asthma of their sound

As the frozen carousel beats a pace for the rigid wildness of this wooden zoo …

Oh it's Christmas again, a time for famous feasts.

Bitter laughter interrupts this depiction of a winter carousel, a bestiary of skewered and friendly shapes. “Bring it on, bring it on,” a voice counsels, somewhere between hype and premonition. This passage is relatively unadorned, where the band fades into seeming distance, trailed by a woody, chordal bass, until only a hoarse gospel vocal remains amid an ambient aviary. “Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,” the singer moans; interlacing a known lyric of natal alienation and its spiritual destiny with secular diatribe:

Painted horses pump their riders up and down

While flashing lights make alloyed tinsel gleam

And clinging to their naked steeds

The strapped-on children condense upon the frigid air the steam of life’s suggestion,

They spin and spin and spin and spin and spin in perfect circles, they clutch their beasts

And smile like snow is falling.

Now outside the park they will marvel at the marvels of the frosted scene,

There otherwise retired men play bells and songs

And beg good deeds beside red paper chimneys

As they stand padded in the cemetery and smiles of Santa Claus dressed for December’s Happy Hallowe'en …

As a polyester beard chafes a day’s stubble, this re-paganized, proletarian Santa is an emblem of a fundamental social separation—of goodly appearances and desperate occupation, of worker and consumer, of value and favour. As usual, the uncanny appears as so many misplaced trifles, infiltrating expectation; in this case, an episode of mortal sniffles upsets the Christmas diorama. This small symptom of humanity is enough to attract and provoke the child’s-eye-view that the poem adopts:

One child seems shocked that one old Santa has the sneezes and a running nose

But treats are all and tricks forgotten

As the burning beads and baubles

Reflect the frozen neon flakes.

All flashed silver and then holly red

All this pretty pageant sprinkled with the season’s bursting horns

Of candied brittle-chew and ribboned sweet

Tempts the magic millions racing through the streets.

“Oh, I like that!” Roach digresses, as Pope’s horn enters for the first time so far; hard of tone and chasing the drum. “Ohohoho,” Roach laughs bitterly, affecting a hacking cough as if in character, pushing the band’s meander to its crisis. His own playing is prosodical, snare cracks and cymbal pushes impelling the street sermon forward:

Children pause to hear the uniformed Salvationists

Playing trumpets in the cold,

They gaze upon the glowing cracks and commerce of the windows,

See the sparkling bottles all wrapped in swaddling foil

And they know the urgency of receiving nice before they spoil.

The snow makes a briefly new ecology and suddenly the world is white

And no one now recalls any scene or sight

When Jamestown was an un-sought court

And Black Africa found a darker night

Among white Christians and their sacred sport.

Here arrives the rub, as the poem cinches a sonic articulation of disparate climates and cultures with reference to the transatlantic passage of enslaved Africans during the seventeenth-century—from present-day Angola to the “unsought court” of Jamestown, Virginia, where British colonists enshrined the practice of slavery in North America, imposing their religious customs and selective graces. “It’s Christmas again,” Roach howls with bitter ambivalence, as if to curse the carousel of history and its static, returning representations. For Roach, denouncing colonial rote, the tears of Christ and martyrdom of saints only recall a nearer history:

Beneath the skull and in the brain the capillaries function

Wary of gospel’s martyrdom of Lachrymose Christi

Kept in Sunday schools of magic.

Relearned the mandatory lessons: thus, Supreme his unction

God is good, and who is three times conjugated? Well, God:

The Father, and the Son, and the Holy Ghost—

Like broken arrows in a bow were Saint Sebastian

In the nude and Saint Martin in the field—

Pain pain pain is three dimensional. Triangular is man.

It’s Christmas again, yes it is Christmas, a time for famous feasts.

The monologue trails off in laughter and birdsong, unassumingly as it began, and one hears the sounds of children playing as the side abruptly fades. The album’s b-side, ‘Christina,’ sends a tender letter to a feminized Christ figure, Mary and Child in one: “You have taken harsh grace, an instruction from the skies, and bathed by guilt, you first ignite, then snuff out, that sudden flame where blood and marrow boil.” This esoteric address, adapted from Wright’s poems ‘Christina Leit-Motifs’ and ‘To Be Dazzled By The Racing of Her Blood,’ transpires atop more fluid interplay, where a breezy vamp supports guest solos by Lee Konitz and Tony Scott, with Tommaso Lama on guitar.

All told, It’s Christmas Again is one of the stranger outposts in Roach’s vast discography—at once a sound collage and meta-spiritual; a one-act play and panoramic soliloquy; and a neglected document of one of the great quartets of the nineteen-eighties at its most experimental. For one thing, it’s wonderful to hear Roach’s voice at such length; his pacing and cadence compounding levels of irony sourced from an underrated oeuvre; and this lengthy disquisition only clarifies the sense of what’s at stake in his reverent, liberationist gospel engagements of the 1970s. Like any seasonal ritual, It’s Christmas Again stands to many listens, and reveals more of itself with time.

A note on the text: The transcription of ‘It’s Christmas Again’ is my own, with provisional line breaks corresponding to the pace of the delivery and checked against Bruce Wright's own choices on the page. Roach's recitation significantly embellishes the original, stretching and expanding many of Wright's formulations, so the above should be read as an average of two distinct versions. Wright’s own poems, which Roach freely combines, appear in the collection Love Hangs Upon an Empty Door: The Poetry of Bruce Wright (Barricade Books, 1998).