Kill from the Heart

For Steve and Gary

When I heard that Gary Floyd had passed, Age of Self was in the studio, mixing a cover of the Dicks' classic 'Kill from the Heart.' Floyd's lyrics filled the room on playback, and I could hear his nasal bellow buoying my own rasped delivery. "You're messin' with REDS who're gonna kick your ass," we sang together, decades and generations apart. It's a signal anthem by a legendary band, seethingly ill-disposed toward bourgeois society and its heirs; hardcore country blues from the heart of Texas, only preferring burning flags to Burnet.

The Dicks are typically reduced to their most sensational predicates—and as far as controversy goes, a gay communist punk band in the middle of Texas practically markets itself. Truly, the Dicks were 'out' in every sense. And unlike the brunt of so-called queercore, which tends towards a kitsch thematization of gayness as a two-note gimmick, the Dicks were not a schtick but a form-of-life: "Out in the desert sands, the Dicks were hatched," Floyd sings on their debut. 'Dicks Hate Police' remains one of the most scathing records that I've ever heard, and Floyd's ire would go on to fuel two classic lineups, based in Austin and San Francisco respectively; each with a classic LP and an equally declarative single to their common name.

On these records, Floyd gave full voice to a spate of collective vendettas, drawing from global movements for peace and socialism and placing the Dicks apart from the parochial, suburban angst of hardcore punk. In obligatory fashion, they got in their swipes at new wave and wealthy jocks; but even these songs bristle with class resentment and revolutionary venom. Where the disaffected kids of hardcore largely failed to differentiate between a capitalist enemy and any number of cultural scapegoats, professing straight, white, artless disaffection as such, Gary Floyd provoked the right people, and sourced his chronicle of transgression from direct experience. Unlike the contrived offence of vastly inferior punk bands, the Dicks "punched up": at killer cops, at the shiftless rich and their teenage scions, at white supremacists and their apologists, at despondent CEOs, at "bourgeois fascist pigs" and "apolitical assholes" alike; the list goes on, and everyone of these indictments makes a proper anthem.

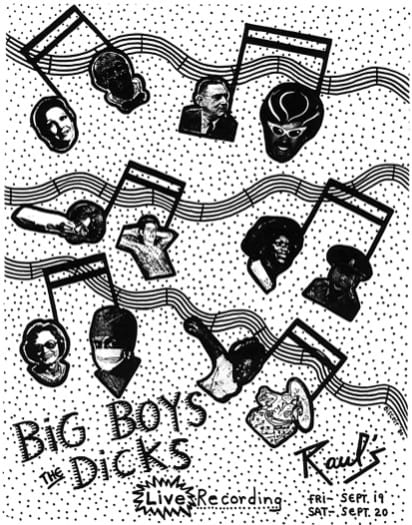

Better still, this righteous negativity was always backed by a raucous party atmosphere, particularly in the recordings of the classic Austin lineup. From the shabby singalong of 'Anti-Klan (Pt. 2)' to the seemingly interminable punk-funk coda of 'Dicks Can't Swim,' Kill from the Heart feels like a compilation of musical highlights from a bleary, all-night hang. This oppositional sociality is better evidenced on the essential Live At Raul's Club album, a split with their fellow travellers in the Big Boys—one of very few punk bands who could hold their own next to the Dicks in terms of idiomatic depth, or why not, soul.

The 1980 LP is as good an example as punk has furnished of what Fred Moten and Stefano Harney call the informal, in music and life alike: "the experiment with/in the general antagonism," Harney says; "and then the song starts." In the recorded music of Marvin Gaye, "you can hear the audience, you can hear the crowd, and then he begins to sing ..." On these recordings, the song emerges from its total social circumstance as if already underway, a momentary specialization of the general creativity immanent to its milieu. (Floyd remarked of the band's original drummer Pat that "a song's ending never meant he stopped drumming, but that loose style worked well for us.")

On their side of Live at Raul's Club, the ambient din of the crowd frames each take, and Floyd's banter greets the comradely heckle in kind. 'Saturday Night at the Bookstore' spans sceneries in its seedy effrontery; a portrait of gay social space and its unspoken permissions, sending up the homoerotic rituals of hardcore in a graphic confessional. The song is addressed to a nameless hookup, a suburban closet-case on the other side of a glory hole, whose social profile otherwise resembles the class antagonists of Kill from the Heart; but Floyd's ongoing monologue faces the crowd, returning their abuse as a form of extreme flirtation. "Hey, I want to suck your dick after the show motherfucker. Throw another beer can at my asshole. I've seen you in the bookstore!" The song's verses are inseparable from this extemporized torrent of abuse, and Floyd cruises the pit as he interpellates the listener: "I'm at the bookstore, I'm at the bookstore," he taunts: "You're at the bookstore too!"

The Dicks' classic Austin lineup sounds unlike anything in punk, especially today, where their lascivious swagger feels actually subversive. "I'm a child of sodomy," Floyd declares, completing the myth of queer autopoiesis set forth in 'Dicks Hate Police.' In their brazen recruitment from subcultural disenchantment and the outskirts of straight society, the Dicks give social form to that most feared figment of reactionary fantasy; the reproducing homosexual and their alternative, affirmative kinships; an antagonistic obverse of conservative pro-natalism and its closed family values. Remember, the Dicks weren't born—they were hatched, like a plan or conspiracy.

After a month of corporate Pride events, including flashes of sanctioned resistance to liberal inclusionism, it's hard not to feel that homosexuality has been politically exhausted; but the music of the Dicks in all its flouncing biliousness reminds us otherwise. As the far-right hastens its retreat to an all-but-fortified nuclear family and the ruling class frets its replacement by the wretched at the gates, Gary Floyd's songs of gay menace feel targeted as ever; shot from the heart in self-defence.

Needless to say, I've been playing a lot of my favourite Steve Albini records this month, stunned afresh at how many top-shelf, life-changing recordings he helmed. It's hard to pick my favourites, and I had to leave many of them off of a cursory playlist for Radio State. This is a sentimental round-up and not in any way definitive–the first Slint record sounds pretty awful, for example, but it's a mood; and the self-titled Purplene album, underrated in its time, could as soon represent my frustration with the smaller sound of Jawbreaker's 24 Hour Revenge Therapy, otherwise one of my favourite collections of songs. (Embarrassingly, I chose 'Condition Oakland' for this episode, which as I now recall was probably recorded by Billy Anderson in San Francisco.)

The best Albini sessions, to put things a touch too modestly, capture the sound of actual music in real rooms; and my favourite records tend to be those most representative of space. Oxbow's Serenade In Red is still one of the biggest, gnarliest sounding records of a decade; a work of heaving menace, more neo-noir than rock'n'roll, and the band's elastic performances are well-served by the wide dynamic range of Albini's recording. On the hushed end of a provisional spectrum, Albini was the truest documentarian of Low's live sound on their fourth and fifth albums, Secret Name and Things We Lost in the Fire. Before any chamber-pop embellishments, the band sounds simply perfect; clear voiced and serenely paced in rooms cathedralized by slow decay.

This gift for contrast makes the greatest Albini records: Mogwai's My Father My King could have become a modal murk in less capable hands, but layer by layer it makes a purposeful ascent, more linear than meandering; and the nu-tribal pummel of Neurosis stands apart from hundreds of imitators for its clarity of tone and glacial depth. If anything, it became easy to take Albini for granted because his standards were so frequently duplicated by other recordists; and in an age of maximum compression, his name became synonymous with the natural beauty of aggressive music.

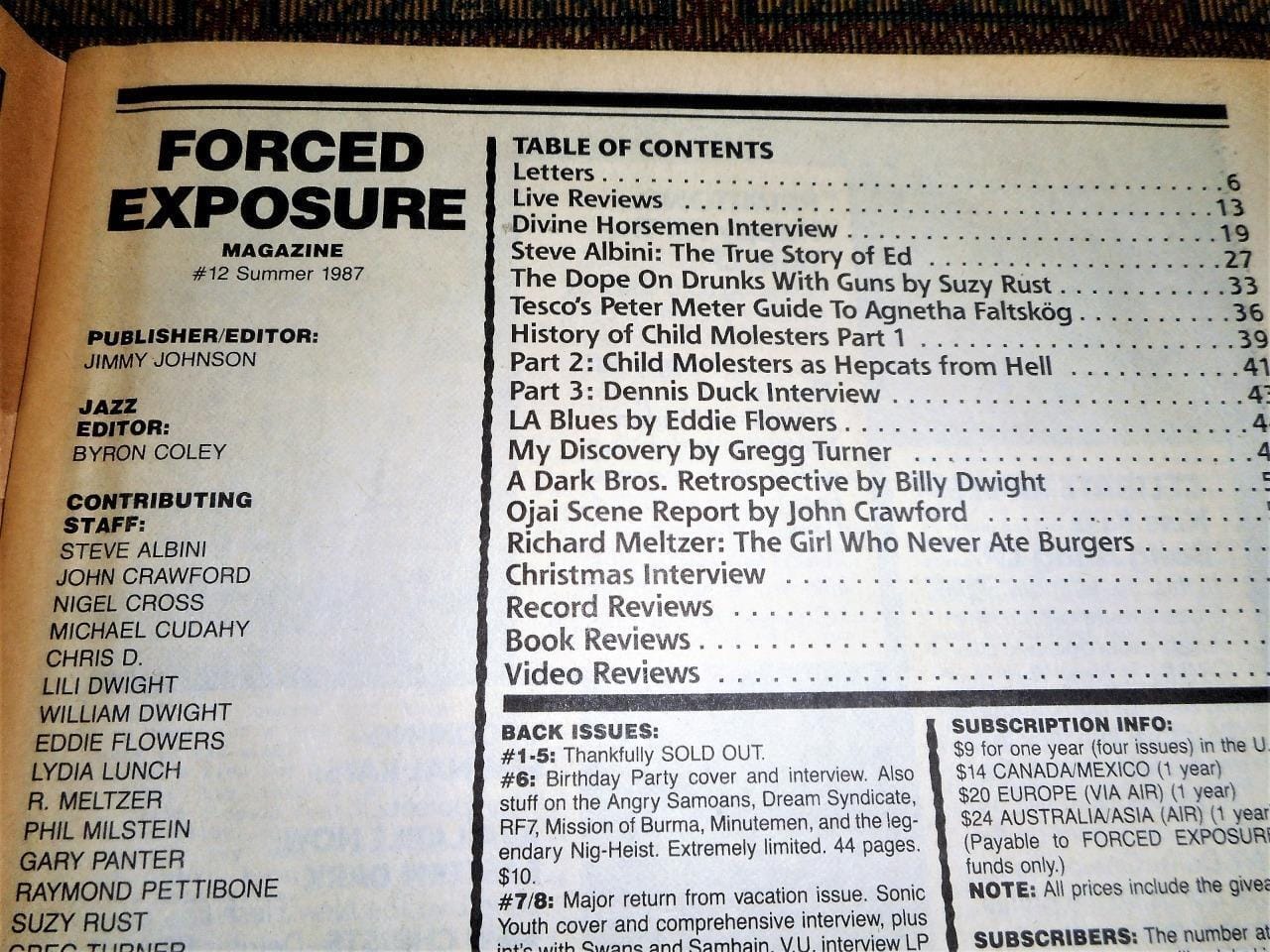

Albini's own music has its decided highs and lows; the latter obviously concerning the uncaring provocation of his earlier groups. I love Big Black, and most of us had made up our minds about the ugly excesses of their aesthetic of transgression years ago; but the debut of Albini's more reflective noughties persona nonetheless arrived as a relief. "A lot of things I said and did from an ignorant position of comfort and privilege are clearly awful and I regret them," he wrote in a 2021 thread on Twitter. "It's nobody's obligation to overlook that, and I do feel an obligation to redeem myself."

This language squares better with Albini's longstanding position as a paragon of indie purism. In spite of having recorded some of the breakthrough records of punk's mainstream turn, Albini's disdain for major labels and their parasitism was the stuff of infamy: "Don't sign anything," he cautioned, and it's still good advice. His bleakly hilarious 1993 screed 'The Problem with Music' begins with a paragraph of Dantean effluence, imagining the industry as a shit-filled trench and every indie rocker as a willing swimmer. Albini's prognosis on streaming was similarly dim, but with a glimmer of hope in collective action: "The labels should pay the bands fairly. If they won’t do so voluntarily, then the governmental trade and communications oversight bodies, quasi-governmental PRS agencies, and affected bands as a class should force them to by bringing action against Spotify and affiliated labels." Emphasis mine, but what an exhilarating thought.

The most recent, suddenly posthumous, Shellac album confirms the distance Albini had travelled from his race-baiting days, at the same time as Shellac's consistency invites comparison across the years. To All Trains is great "late Albini"; sarcastic monologuing without the malice of earlier years; an elder noise rock tempered of deeper insight and humility. The group's micro-fictional knack is intact, absurdist and succinct; though the suicidal dirge 'Wednesday' could have been written by a Larkin or MacNeice.

This is midife miserabilism, and Albini's voice sounds more plaintive than aggressive, alternating wry one-liners and the odd lead vocal by bassist Bob Weston. "I'm through with music from dudes," Albini sings half-accusingly on 'Chick New Wave,' a male-feminist imposture or possibly sincere attempt at ethical consumerism in rock, revelling in performative contradiction. It's hardly the manifesto one might prefer; instead, we get a meta-chauvinistic inside joke, marking growth but mocking its imperatives. Like so many mid-age stand-up comics who have weathered cancellation, Albini's bit presumes the benefit of goodwill. And to be fair, it's mostly granted.

For my part, I get that a lot of this stuff is to music as "locker room talk" is to sport; maybe it functions identically, as a worse-than-innocuous, homosocial ritual whereby the aforesaid dudes titillate one another in verboten language and test the limits of their narrow experience. In this respect, much of the meekly transgressive art that Albini made and championed throughout his career demonstrates a genre-specific adaptation of a timelier condition, call it "reality crisis," that includes escalation trends in everything from grisly TV procedurals to unlistenable NSBM to maudlin autofiction. Everything is getting harder, crueller, closer—in style at least, as substance gapes.

But the contemporary quest for substance ends in socio-symbolic impasse, where this direct approach to the Most Real transpires on a strictly imaginary terrain—as if the most authentic realms of experience must also be the most traumatic. In this striving to feel, it intuitively follows that the worst thought one can summon must also be the truest and least mediated intimation of reality. Albini remarked that the work of his peer Peter Sotos is "shocking to your core in the way that the horrors of the reality of those things should be"—but what sort of complacent circumstances call upon art to induce shock in the first place, and for its own sake?

Albini's own periodization of this trend is surprisingly insightful. "If anything," he writes, "we were trying to underscore the banality, the everyday nonchalance toward our common history with the atrocious, all while laboring under the tacit *mistaken* notion that things were getting better." It's a better-than-expected account, and I often think of the shock tactics and general seediness that proliferated in the 80s and 90s as a response to the implied permissiveness of the so-called End of History; just so many attempts to find pleasureful traction on a frictionless plateau. In the advanced capitalist countries, where youth culture persists as sanctioned rebellion, the march of progress to nominal rights for all appears secure; yet this expanding franchise is inexorably linked to all manner of dispossessing and deregulating operations in the economy, manifesting contradictory effects in the cultural sphere.

The future will be like the present, it was said, but with more options; a pell-mell of novel inclinations that eventually express the same. Among countless other enabling factors, this massive depreciation of language and symbol surely strengthens the artist's delusion that hateful speech in fact antagonizes a top-down moral order rather than any specific party or oppressed. And ironically, it was the most illiberal artists of the post-punk era who best took instruction at the finish of the Cold War, where even the thorniest gestures re-express an empty, liberal formalism; granting every point of view equal immunity as so many exhibits in the finished arc of our ideological evolution. (Call this "our common history with the atrocious," presumed retrospective.)

For what it's worth, I don't believe that it's a matter of simple human decency that our music scenes are more sensitized as a whole to the sort of scumbag behaviour that used to pass muster. And I don't think it's quite so simple as that liberalism solved this problem on its own terms, by enrolling more and more interests in popular expression such that the old pathologies and their associated types were schooled and cornered. Rather, I'd guess that the return of history—of class struggle and the prospect of revolutionary social antagonism—raised the stakes for provocation and restored to art a sense of its communal calling, sorely lacking from the arid eighties and the jaded nineties. This isn't to understate the role of feminist and anti-racist movements in the education of a Steve Albini, but to take him at least partly at his word. For years the man waged flame-war in the service of social and economic justice; coarse and politically incorrect as ever, only with a heightened sense of care and, dare I say it, duty.

I didn't know Steve Albini, but he always struck me as one of the few survivors of a politically dismal era who was conscientious enough for the task of self-criticism. There aren't many of them; and more of our heroes have gone the way of reaction, bellyaching about a generationally endemic "sensitivity" as if it had the backing of a police. On the contrary, in response to a rash of specials by "anti-woke trans-bash comedians," Albini cut straight through the whinging bullshit of the bully millionaires and their online infantry: "We are what we pretend to be," he wrote. "Indulging the pretense eventually becomes so comfortable that it fuses with the person underneath. I've seen it happen up close, with people I called friends, and it demands the self-reflection people of my generation have failed at."

Albini might have pushed too hard at times, but he had no truck with the authors of our moment and their real antagonism of our limited freedom. And when the "Ed Gein humour" of Big Black and peers found its historical limit, he actually drew back. I also think he helped a lot of people make a lot of music that has made the world a slightly better place, to the extent that any of this matters. As for his detractors, who cannot be discouraged even now, I'd guess that they lack both an ear for grandeur and a taste for grace.

To All Trains ends with 'I Don’t Fear Hell,' a lolloping, sarcastic elegy to, well, everybody, or a generation and its fond mistakes:

Something something something when this is over

I'll leap in my grave like the arms of a lover

If there's a heaven, I hope they're having fun

Cause if there's a hell, I’m gonna know everyone

It's a haunting note on which to end a long career, though one could offer that Albini's morbid humour generated many would-be epitaphs but for the punctuation mark of sudden death. Even so, it's sickly, sweetly fitting that this one should stick. Albini faced the music, as he built a legend of undoubtable resilience. With him goes an era, which could even bear his name; and by any measure, we're fucking lucky to have been there.