Mutatis mutandis

On Sam McPheeters' Dim Visions of Punk

In the depthless world of hardcore punk, ambivalence is an uncommon affect. Apathy abounds, and moral surety, of course. Both have their formidable discographies. But where are the paeans to uncertainty and self-doubt? Punk’s brevity leaves no time for hesitation, and sheer will plays well on record. But after the gig, what remains of that unbridled rage, or positivity? Could it be that hardcore, in all its tidy pride, has been repressing something?

Dissonant and melancholy, brainy and bilious, Born Against stand out among even superlative peers for their conviction and wariness of conviction at once. Formed in 1989 by vocalist Sam McPheeters and guitarist Adam Nathanson, their discography is one of the most tonally complex and aesthetically ambiguous in a rapidly politicizing era of punk—an implicated critique of the New York hardcore they would taunt and exalt in equal measure.

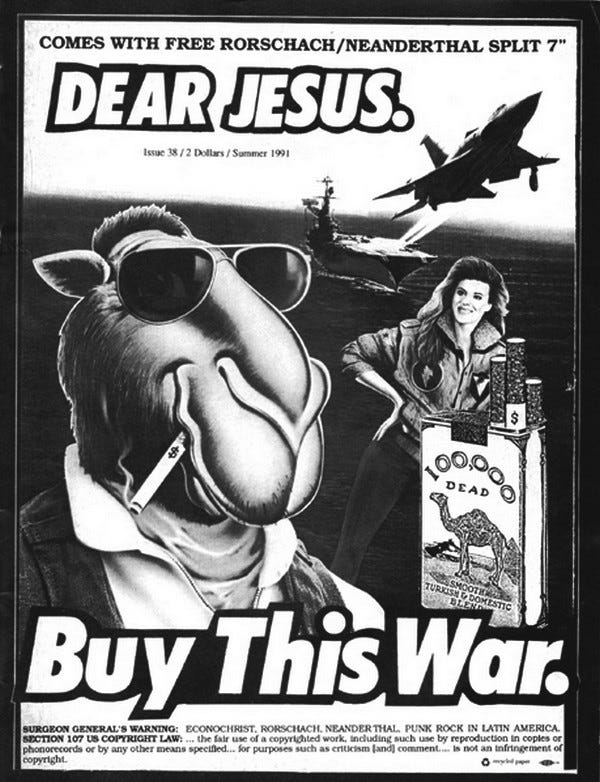

On records like Nine Patriotic Hymns for Children and Battle Hymns for the Race War, Born Against set out from the facetious, aesthetic fascism of avowedly leftist bands like Reagan Youth, but in an updated and distinctly American idiom; lacing gospel tracts and clips from radio call-in shows throughout their own archly apoplectic agitprop. Like the Dead Kennedys before them, Born Against didn’t just write diatribes; rather, their records made an ideological collage of the wrong society, setting forth the views they would oppose within a single song.

In the last half-decade during which punk could plausibly claim autonomy of mass culture, Born Against directed a perplexing traffic back and forth between hegemonic and resistant discourses, ultimately acknowledging that punk is far from unique in its attempt upon the means of ideological production. Christian zealots and far-right proselytizers have their own resilient underground and media apparatus; and over the course of his music and writing life, McPheeters repeatedly suggests that a properly contextualized understanding of punk is necessary to any thorough account of the new right and its discursive tactics. In 1989, however, Born Against was far-seeing in this comparison, staging a series of subcultural wars of position as they isolated themselves from an increasingly stylized and restrictive form of life.

Righteous outliers of the New York hardcore scene, constantly enveloped in internecine spats, Born Against lasted for the four years allotted to great punk bands. In that time, they did more for punk as a progressive culture than almost any other hardcore band, and that legacy doesn’t end with their dissolution. McPheeters would continue performing alongside former Born Against member Neil Burke in Men’s Recovery Project, unleashing a formidable discography of high-low concept comedic punk; and in the naughties, his band Wrangler Brutes would blend noise rock with mordant humour on some of the century’s best punk records.

Since his hardcore heyday, McPheeters has turned his attention from zine-making to journalism, as suits a rapidly changing technological episteme, and published two novels, The Loom of Ruin and Exploded View. McPheeters is a fantastic writer—ribbing, cynical, and surreal—and his literary prose bears many of the hallmarks of his lyrical style as it extends a proud Californian tradition of paranoid noir. (Born Against lyrics were co-written by McPheeters and Nathanson, though often attributed to their sole vocalizer.) As a journalist, and one of the few interesting contributors to the utterly needless Vice magazine, McPheeters mixes gonzo digression and sober reportage, searching for the conjuncture in all manner of cultural effluent. This is post-punk journalism, scrappy and snide when it means to be, and some of his best-read pieces confront this music directly—a 2008 profile of 26, former vocalist for The Crucifucks, is rich with non-judgemental detail and bittersweet cues to (dis)identification. “Middle age is hard on radicals,” McPheeters notes, “but it is harder still on radicals for whom showmanship has been their primary form of activism.”

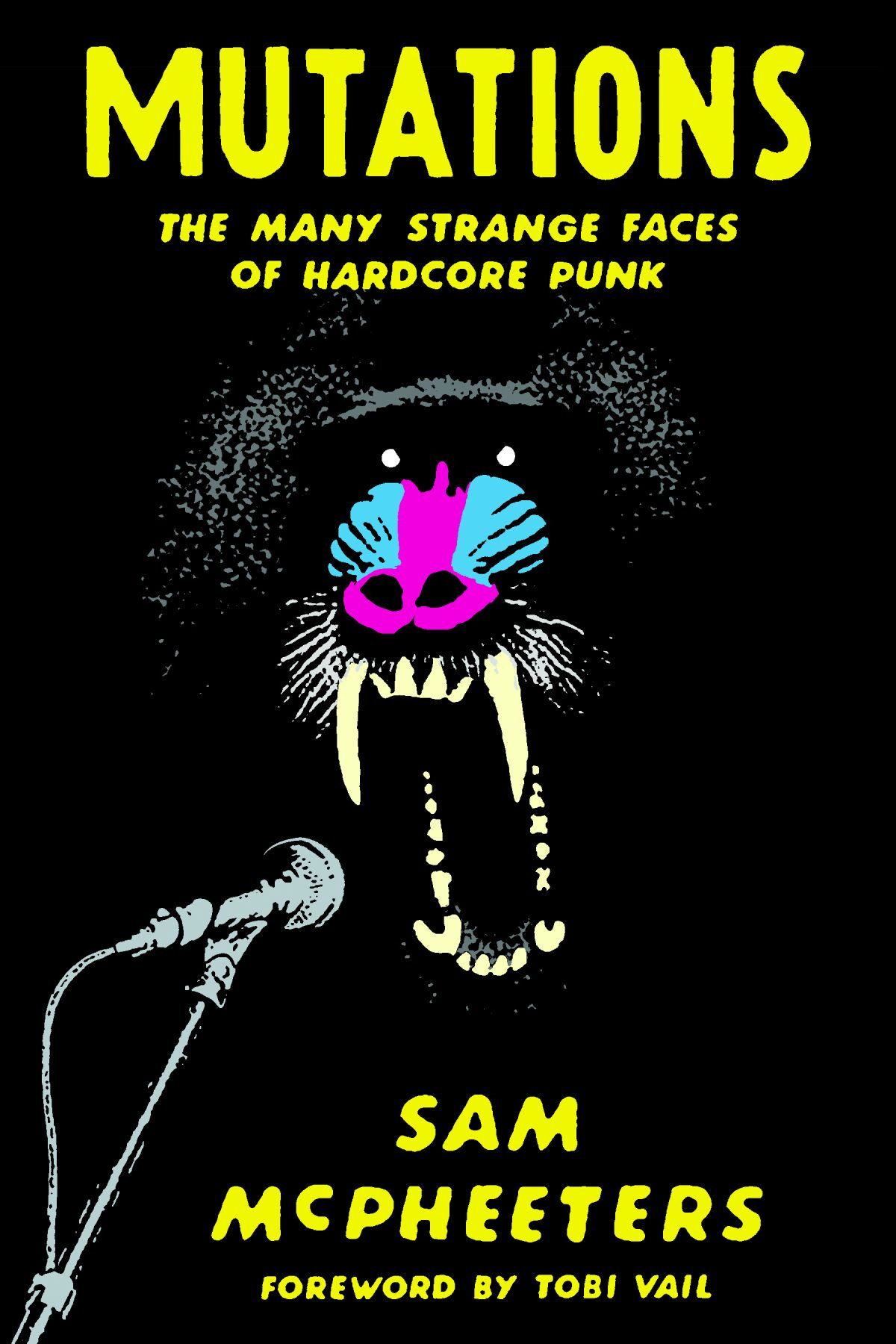

There’s a half a lifetime of insight in that remark, but McPheeters’ own punk memoirs have been slow in coming; forestalled by a sometimes apoplectic self-loathing, stagy and sincere, that colours most of his remarks on this earlier body of work. So when Mutations, a collection of his personal and journalistic writing on punk music, came out in 2020, it felt as if an embargo had been lifted. Mutations is a gratifying, often frustrating, book, constantly disparaging the projects and contexts that impel an ideal reader’s interest. As one expects, McPheeters is unkind to Born Against, whose legacy furnishes this book much of its anecdotal content; still one detects a hint of pride, however wounded and transformed, in his account of bygone days.

This vacillating recall is far more relatable than most been-there-done-that accounts of past punk activity, where it implies an ongoing attachment, however complex. “The intensity of wrestling with ideas in public can often look ridiculous to those outside the process,” McPheeters writes, and where the insularity of punk-as-process is concerned, that uncertain tussle is preserved as just so many headstrong stances. These pile up for us to live down, drifting ever further from their proper context.

McPheeters’ most vivid account of this difficulty concerns the infamous Born Against-Sick Of It All debate on WNYU, in which the two antithetical crews met to discuss the ethics of the music industry and nearly came to blows. This self-administered hazing circulated on bootleg tapes and CDRs for years afterward, a time capsule of a fractious scene. On paper, it sounds great—Born Against performing the role of an upstart intelligentsia to Sick Of It All’s thoughtless authenticity. In practice, McPheeters explains, it didn’t go so well:

Since their persona (working-class guys) was genuine, and our shtick (outraged truth-tellers) was acquired, we’d needlessly handicapped ourselves from the start. The debate ended with (Sick Of It All) crashing a chair aside in a manner that made for good radio … At the next ABC No Rio show, I was shocked to learn that our peers disapproved of our performance. I’d assumed I’d get some congratulations for facing tough men and taking responsibility for the actions of the community. Instead, our constituents felt misrepresented.

The WYNU debate is a mutually humiliating melee; all sides completely unpersuasive in their passionate intensity. But the clamour of oneupmanship, the grasping at straws, the rhetorical hair-pulling, the micro-ideological tug of war, are all wincingly familiar—staple social textures of subculture, which holds a magnifying glass to each petty dispute. (“It is clearly not easy for men to give up the satisfaction of this inclination to aggression,” says Sigmund Freud. “The advantage which a comparatively small cultural group offers of allowing this instinct an outlet in the form of hostility against intruders is not to be despised. It is always possible to bind together a considerable number of people in love, so long as there are other people left over to receive the manifestations of their aggressiveness.”)

There isn’t a lot of writing that accurately portrays the vivid, all-involving stakes of this aspect of punk because, well, that kind of a project would require some distance, even disenchantment, which is antithetical to the intensity of feeling that such a project ought to capture. But Mutations isn’t a Vivian Gornick-style ethnography—it is a series of funny, thoughtful essays by a reformed fanatic, who turns out to be an ideal ambassador to a culture of subterranean elitism. Alongside his ample confessions, McPheeters pens pithy tributes to the greats, from Die Kreuzen to the Flying Lizards, grounding this book in appreciation as well as self-deprecation.

At the outset, however, McPheeters professes blank incomprehension of the rituals in which he used to partake, starting with live performance: “if I could no longer summon faith in my own live music, how could I muster interest in anyone else’s live music?” Aptly, this crisis of faith even extends the core value of DIY hardcore—the imperative to make one’s own media, where passive attendance is neither desirable nor practical.

This insider-outsider view sets Mutations apart from a recent flurry of oral histories that vie for immediacy. McPheeters is melancholy at turns, condescending at others, sometimes in rapid succession:

In 2016, I drove past the Glass House, Pomona’s dependable midsize venue, and saw Discharge was playing. I muttered “yuck” at the line of black-clad youngsters snaking down the block in the rear view mirror. Then I remembered they’d been my favorite band for thirty years. Why is life dumb?

Here we see another face of the disenchantment glossed above, where self-disparagement runs into anti-social superiority. True, punk necessitates the dirtying of one’s hands with the raw stuff of its rough-hewn sound; but any total identification will eventually traverse the twin antipodes of narcissism: all-involvement or complete despair. This can even be productive—hardcore isn’t known for moderation, after all. But this binary structure of attachment surely contributes to the uneven historicization of punk music, where a glut of primary sources—zines, posters, records, and all manner of ephemera—are framed or liquidated by lapsarian cranks. I think of Stephen Blush’s American Hardcore book, shot through with misogyny and error, which conveniently periodizes US punk in terms exactly corresponding to the author’s own attention span. Too often, punk rock has a vengeful ex as its biographer.

McPheeters’ love, however, feels more unrequited than revoked; and in an amiable interview with Aaron Cometbus, whose faith in and patience with “the” DIY community remains, McPheeters explains himself with grace. “I’m surprised to hear you talking about hardcore,” Cometbus remarks. “Why return to the subject now?” McPheeters responds:

I think you’re confusing how I felt about my own output with how I felt about the genre. I get this a lot. Even when I was in Wrangler Brutes, I was frequently accused of somehow mocking hardcore by touring in a hardcore band. It was weird. From my perspective, I don’t see how anyone could look at my deep level of immersion and think, “There goes a guy who hates underground music.” People don’t know what to make of artists who don’t like their own past art. For me, the right to regret mistakes is fundamental. This subgenre—underground, hardcore, whatever name we’re using—is saturated in self-congratulations. There aren’t many people in my position. I’ve always loved hardcore. I just don’t love my own contributions to it.

Such misgivings are surely a residue of punk’s tacit commandment to get thee a band, there to channel one’s earliest indignations. But McPheeters’ account of his years as full-time provocateur is highly qualified, tending carefully to the many social mediations that cleave and compose punk habitus. Moreover, as he notes, this considered distance isn’t a mid-life, retrospective development— throughout his time in an active hardcore band, his participation was already marked for suspicion on account of its ironic distance from punk ritual, a double flouting of rock archetypes in their dense refraction of race, gender, and social position.

As the Sick Of It All debate lays bare, hardcore has always been divided by class: advanced by the entrepreneurial verve of prodigal children on one hand, and the concrete knack, or lack, of waged teenagers on the other. McPheeters is candid about his own changing class position throughout his time in hardcore, as well as the anxiety that attends this fluctuation, where Born Against and his label, Vermiform Records, were significantly underwritten by an unanticipated inheritance. “The trust fund didn’t fit into my existing world view,” he states plainly. “My life centered around hardcore”—which is, among other things, a bootstraps ideology of puritan thrift.

At bottom, every party to the WNYU debate subscribes to some version of this myth of self-sufficiency, with Sick Of It All’s blue collar pride (“blood, sweat, and no tears”) on one side and Vermiform’s fiercely voluntaristic separatism on the other. Caught in a miniature recapitulation of radical organizing and its impasses, Born Against are unable to move the needle on any topic of professed concern, because their highest ideals come from elsewhere than the workaday. (“This is our job,” Sick Of It All insists in defence of their relatively major label’s business practices. “You wouldn’t work a job without getting a raise, this is our raise.”) Needless to say, the WNYU debate was a non-starter, but McPheeters’ account feels climactic in its staging of a creeping personal compunction:

As a leftist hardcore act in the vein of Dead Kennedys, we’d produced some interesting art. As a lifestyle choice, the experience left a bitter aftertaste. Singing for a “confrontational” band, it turns out, sits in the shallow end of the pool of human activities. What is band touring but the use of resources—yours, others’, everyone’s—to move from town to town, striking poses in front of witnesses? If the poses are good, artistic fulfillment can cover lapses in motivation. But if the poses are politically confrontational, and thus dependent on audience reaction, motives can wither.

This self-criticism connects to one of the book‘s more compelling subtheses—that the broad humour and ironic pastiche of eighties hardcore is itself highly uncertain, and equally amenable to the purposes of a mercenary right. Regarding Born Against’s own contribution, McPheeters is unsparingly clear: “Our lyrics trafficked in anti-racist, ironic racism whose sarcasm would be difficult to explain to a layman listener.” The song ‘Set your AM Dial for White Empowerment’ lambasts Rush Limbaugh and ilk, but the title, lacking context, doesn’t travel well. ‘$5 An Hour’ (“See the white wreckage, the ones who couldn't afford to leave the white pride”) addresses the uneven administration of the wages of whiteness, but not without littering slurs for impact.

The risks of this approach are all too real where everyone encounters hardcore as a non-initiate (a “layman,” in McPheeters’ words) and its repellant tropes can double as an entry test. I first investigated Born Against after hearing hometown heroes Propagandhi mention them on mic, and I remember searching out their final LP and experiencing a real moment of confusion at the tongue-in-cheek delivery. Of course, they were hardly alone in this approach. McPheeters mentions the Dead Kennedys, and Jello’s tongue-in-cheek personae trumpet everything from nuclear eugenics to police brutality to total surveillance. Something about these lisping soliloquies, however, like many a zany typeset, precludes any mistake as to their intent.

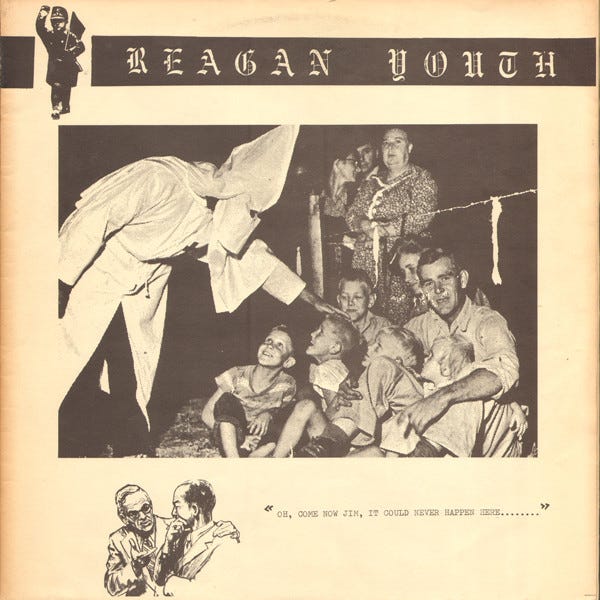

In 1984, New York’s own Reagan Youth sang “We are the sons of Reagan, Heil! The right is our religion.” Their mini-LP, Youth Anthems for the New Order, is a clear template for Born Against, depicting a Klansman blessing a gaggle of white children. Reagan Youth represented a leftmost extreme of early New York hardcore, and it’s unlikely that anyone was long deceived by their reverse marketing strategy. But this semiotic duplicity makes ample way for pleasure: in the case of the Dead Kennedys’ famous “Nazi Punks Fuck Off” armband, for example, the swastika is hardly annulled—one gets the latent kick of wearing a Nazi insignia in plain sight, whilst manifestly opposing its potency. Without venturing too strong a thesis as to satire’s permissiveness, nor punk’s bad negativity, it seems noteworthy that between the first Reagan Youth and Born Against records, explicitly neo-Nazi bands like YDL would come to infamy among the New York hardcore scene, gigging openly and appearing alongside Warzone, Sick Of It All, Gorilla Biscuits, et al on Revelation Records’ otherwise definitive New York City Hardcore: The Way It Is LP.

Boston, not New York, furnishes McPheeters his case study in the casual racism of early hardcore, where bands like Last Rites and SS Decontrol flirted with Nazi iconography as a matter of course. “The half-life of the overt Nazi imagery from Sex Pistols era was perhaps longer than most thought,” McPheeters writes. “A lot of bands played footsie with racist imagery without doing the basic math on how this would make them look to outsiders.” Once more, this error says a great deal about the composition of “the crew” to whom such humour catered. As McPheeters elsewhere notes, this style of provocation is apparently smoothed over within the ferment of straight-edge hardcore, which tends as strongly to stiff-necked normalcy. But there’s little contradiction between the family values of this “moral” hardcore and its seedier extremes, where one is the ungagged and begotten secret of the other.

At times, Mutations seems like a litany of error; but McPheeters writes with humour and affection about the larger-than-life characters of hardcore, who appear as if from a cartoon. “I’ve always felt a deep sense of continuity between the mass media of my childhood and the underground media of my teens,” McPheeters remarks to Cometbus. “Monty Python, The Muppets, Looney Tunes… all these zany bits of culture were mirrored by the wacky characters I read about in Maximumrocknroll.” It’s vividly relatable; I can still remember when the tableaux vivants of punk photography overtook my childhood interest in comic books and science-fiction magazines, and how these pursuits were similarly mediated at first. I met punk rock on the page, as a writhing, grainy pantomime, before I was able to access any records.

Ultimately, it’s fleeting feelings like these that McPheeters captures so well in the articles and vignettes he collects. Punk, after all, is a genre of firsts, where debuts and demos take pride of place in a race to stop time; and in its own incredulous way, the essays in Mutations honour this mania for fresh experience. And while it’s difficult to endorse all of McPheeters’ conclusions, particularly if one is a fan of his music, one can at least admire his intent to periodize his own participation as it wanes: “This specific era—the massive wealth of post-Cold War America—is an anomaly in history,” he explains in a post-mortem of nineties DIY. “Not everyone should make art. Not everyone should be in a band. Some people need to farm, and repair bridges, and make socks. Sometimes it’s okay to be a spectator.”

Maybe so—and it’s certainly true that the meaning, and means, of participation have changed since Vermiform closed shop. But I can’t read simple discouragement from this or any of McPheeters’ peevish snap assessments, where punk’s essential negativity, brought to bear on itself, can only tend to unrenunciation. In this respect, like Born Against before, the essays in Mutations demonstrate the ultimate viability of punk from a standpoint of critical participation, even personal compunction—embracing youthful folly as a means of history. It’s also a cautionary tale, where life’s regrets, if properly defended, help to stave off the regression for which punk is improperly known. And really, what could be more hardcore than that?