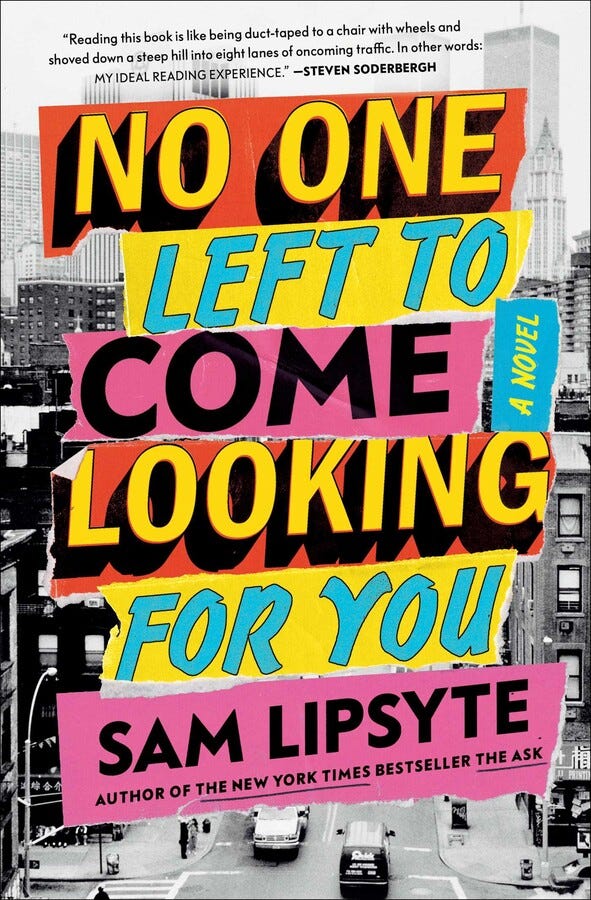

No One Left to Come Looking for You

Sam Lipsyte's Noisy Noir | A Tribute to Rick Froberg

It’s hard to write plausibly about subculture, where writing by its nature means to travel, and subculture tends to, and defends, its place. What are these worlds in their endless inner differentiation to the casual reader? There’s simply too much to capture that eludes the drop-in observation: from the regional grain of in-group lingo to the dizzying array of references, fixing participants in history and space; not to mention the many negative conditions and antipathies that secure a vengeful coziness. And yet, for all this difficulty, the temptation remains. There may be no more literary calling than to draw back the curtain on obscure experience.

At the outset of his influential study, scholar Dick Hebdige identifies subculture with “an Underworld.” This near-synonym bears a whiff of brimstone, where each term implies descent. In this respect, the subcultural enclave provides the perfect setting for noir—a closed and urbanistic genre, typically depicting an illicit company in sordid detail. In the world of noir, all are fallen, or falling; so many dim interiors reflect a narrator’s confinement to a world not of their making—though in every case, inexorably, chosen. Subcultural style, Hebdige affirms, tarries with criminality: its symbols are “the darker side of sets of regulations, just so much graffiti on a prison wall.” Noir too depicts the underside of order, although Hebdige’s particular examples are sociological, not literary; pulled from the seething, antisocial underground of punk.

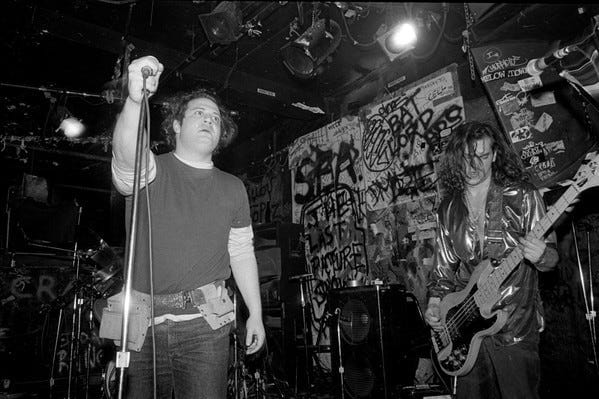

No One Left to Come Looking for You by Sam Lipsyte is a brisk caper set amid the New York garage rock scene of the early 1990s. Lipsyte writes with firsthand knowledge of the odours and informal orders of this bygone milieu, as the former vocalist (“Sam Shit”) of little-documented New York performance-punk group Dungbeetle. The novel centres on the exploits of Jack Shit, bassist of the fictional, fledgling, micro-regionally infamous “neo-proto-art-scuzz” band the Shits. “It’s true, we’ve never been the tightest band,” Jack says. “But some nights we are the weirdest. When we are off, we are terrible. We don’t have competent mediocrity to fall back on. And when we are on, we are still terrible but we are one of the best bands you ever saw.” The Shits, then, are Every Band in aspirational form. This state of grace is fleeting, of course, but Jack’s grandiloquent descriptions of his punk rock imago are performances in themselves.

A petty theft kickstarts the plot—Jack’s roommate, the Banished Earl, has been spotted about town trying to pawn Jack’s Fender Jazz bass for drug money. This is an act of self-sabotage, too, for the Earl sings in the Shits. Says Jack, “his brief includes but is not limited to howls, whimpers, banshee shrieks, declamations, provocations, semi-ironic rooster struts, blind dives into mosh pit, simulated or else revocable genital self-mutilation, and of course, spectacle.” The missing J-Bass stands in as a motivating objet—”no bass, no band”—but the search assumes a greater urgency as the Earl stays AWOL of their shared apartment. It’s not like him, however unreliable in his prickly proclivities, and the Shits have a show in just over a week.

Jack’s search leads him into the darker recesses of the New York drug-and-music scene—a high-stakes sojourn amid the scenery of punk rock’s cultivated seediness. More than a missing bandmate, the Earl is a stand-in for foolhardy vocation; a beatific figure composed of myriad projections. In this case, the noir trope of the missing body doubles the rock trope of the absent singer, each facilitating fervent pursuit. Jack’s neighbourhood interrogation opens old, and relatively fresh, wounds, tapping ex-lovers and ex-bandmates. The Shits’ drummer, Hera, used to date the Earl and is comparatively cool about his disappearance, at first; as Cutwolf, the group’s guitarist, is quickly enlisted in the search.

From loft to dive bar to tenement to pawn shop, Jack’s search dredges digression sooner than it turns up evidence; scouring Alphabet City and settling scores. In this, Lipsyte’s novel joins a critical tradition of noir as neighbourhood preservation, depicting a Lower East Side all but irrevocably altered by a procession of invasive capitals. More than a lapsed bohemian time capsule, No One Left To Come Looking For You is a history of the future in miniature, where one punk’s disappearance stands in for the piecemeal obliteration of a whole form of life and its informal infrastructure.

Leads are few and far between, until a well-known mob enforcer tries to pawn Jack’s bass, and the plot instantly thickens. Heidy—short for Heidegger—Mounce now works for the “big-timers,” a detective explains: “The people who own the city. The Dursts, the Speyers, Trump, people like that.” In an instant, the Vanished Earl’s predicament connects to a slate of proper nouns who own the city. With non-sanctimonious unsubtlety, Lipsyte attributes the individual crime of the Earl’s seeming abduction to a social process, far larger and more insidious than Jack had guessed. That said, Trump’s cameo is in name only, and not even a denouement outside Trump Tower can draw out a villain who must never look his many victims in the eye, nor take responsibility—that much has been designed.

On the face of it, this is well-trod terrain: Jonathan Lethem’s recent noir, The Feral Detective, moralizes Trump’s presidency as it indexes the ravages of gentrification; while Sarah Schulman’s detective novel, Maggie Terry, written and published in the middle of Trump’s term, has aged about as well as a Facebook post. “Everyone was in a state of confusion because the president was insane,” the novel begins. “Social deterioration unfolded at breakneck speed … Meanwhile, back in New York City, the subways either derailed with regularity or didn’t run at all.” In this disquisition, New York’s late trains express a mood of decline, of which Trump and his followers also partake to great advantage. (“We used to have the greatest infrastructure anywhere in the world, and today we’re like a third-world country,” Trump repeated throughout his campaign, making frequent reference to the state of the city that raised him.)

Schulman’s novels are typically sensitive to the urban dynamics and economic factors characterizing political power; but in this opening passage, Trump is depicted as a debauched sovereign, sui generis, rather than the crest of a process that includes his family’s vast property empire, at one time spanning 27,000 housing complexes in Brooklyn and Queens. By positive comparison, Lipsyte’s pre-MAGA, anti-Trump noir is a period piece, depicting the fucker in his more timeless guise—as the bearer of a dispossessing class relation, rather than a subjectively motivated Caligula.

The demotivating, macro-level attribution of street violence is another important feature of noir, and Lipsyte’s fatalism twists the knife. When the investigating detectives propose to “put a cork in this thing,” Jack bristles with indignation. “Just to protect the rich, crooked fucks who run this city?” he demands. “Rock steady, Monsieur Merde,” the officer mocks, as if to say: Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.

In a penultimate chapter, the Shits are reunited onstage in a final, flailing ritual—the end and beginning of an era. For all the references and authenticating lingo throughout, this is where Lipsyte excels at disclosing the inner life of a band. From unfounded confidence to crushing disabuse, strutting to sputtering, Jack’s voiceover conveys the rapidly shifting extremes of performance:

We rip into the song hard, and for about eight seconds it’s pretty tight, but everything falls apart fast. My bass work is too jittery, never quite locks in with Hera’s beat. Dyl’s sonic curtain is more like a tattered camisole. Cutwolf looks around bewildered, a few strings popped. It’s all a tinny, off-key clatter. We haven’t sounded this bad, this anemic, in years. Hot shame presses my chest and the insides of my eyes, but we grind on until the end of the song, finish a merciful minute early.

Moments after this description, naturally, the band is harrowed from disgrace by the arrival of the Earl who, having survived his descent into the underworld, nearly destroys himself for the amusement of two dozen onlookers. “Just before last chorus the Earl’s body collapses, folds down on itself in fast spasms. Tough to tell whether it’s stage antics, an OD, fatal blood loss, or all of the above, and I look over to Cutwolf, who offers up a wince and a shrug. It’s too late to turn back.”

Blurring mimetic and actual violence, the Earl’s self-sacrificial antics appear just in time to save the gig, and too late—both a reenactment of his recent experience, and archaic with respect to escalation trends in pseudo-Dionysian shock rock. It’s bittersweet as written, and especially when counterposed to the fate of Jack’s former band, the Annihilation of the Soft Left—rabidly political alumni of the squatting scene around Tompkins Square Park, their militancy killed by real estate.

Where the real protagonist of this story is the city and its tributary cultures, punk among them, Lipsyte’s closed, caricatural vaunting assumes real significance. “Every subgroup has its own linguistic code,” Jack says at the outset, and his author channels punk vernacular into a bluffing, hard-boiled narrative voice—slightly too smart for its own good and slumming it among the lumpen, as suits both punk and noir. (In his work on noir style, Fredric Jameson notes the preponderance of slang as a distinct stylistic means of disclosing an alienated society: “slang is eminently serial and impersonal in its nature: it exists as objectively as a joke, passed from hand to hand, always elsewhere, never fully the property of its user.”)

Others have struck upon this resemblance: for the noir anti-hero must also be able to access the interstitial and illicit spaces that remain off-limits to most of society; to go underground. In William Gibson’s thriller Spook Country, the journalist protagonist is an ex-member of a fictional post-punk band called The Curfew, whose minor infamy in the early nineties endears her to potential sources as she attempts to unravel a complex conspiracy. Subcultural participation is a passport of sorts, but beyond the point of entry, everything depends upon style—those micro-gestures and impostures by which one properly descends.

These are the little things that stake a scenery, and Lipsyte’s named-and-dated map makes Jack an outpost of a larger, dimly perceptible, world. In its self-taught, sometimes pretentious, specificity, No One Left to Come Looking for You persuasively depicts subculture in two registers—on its own vernacular terms, and by way of the master culture it opposes. That’s a vast and compact—fast and bratty—feat.

‘I Owe You, I Owe, I Owe’

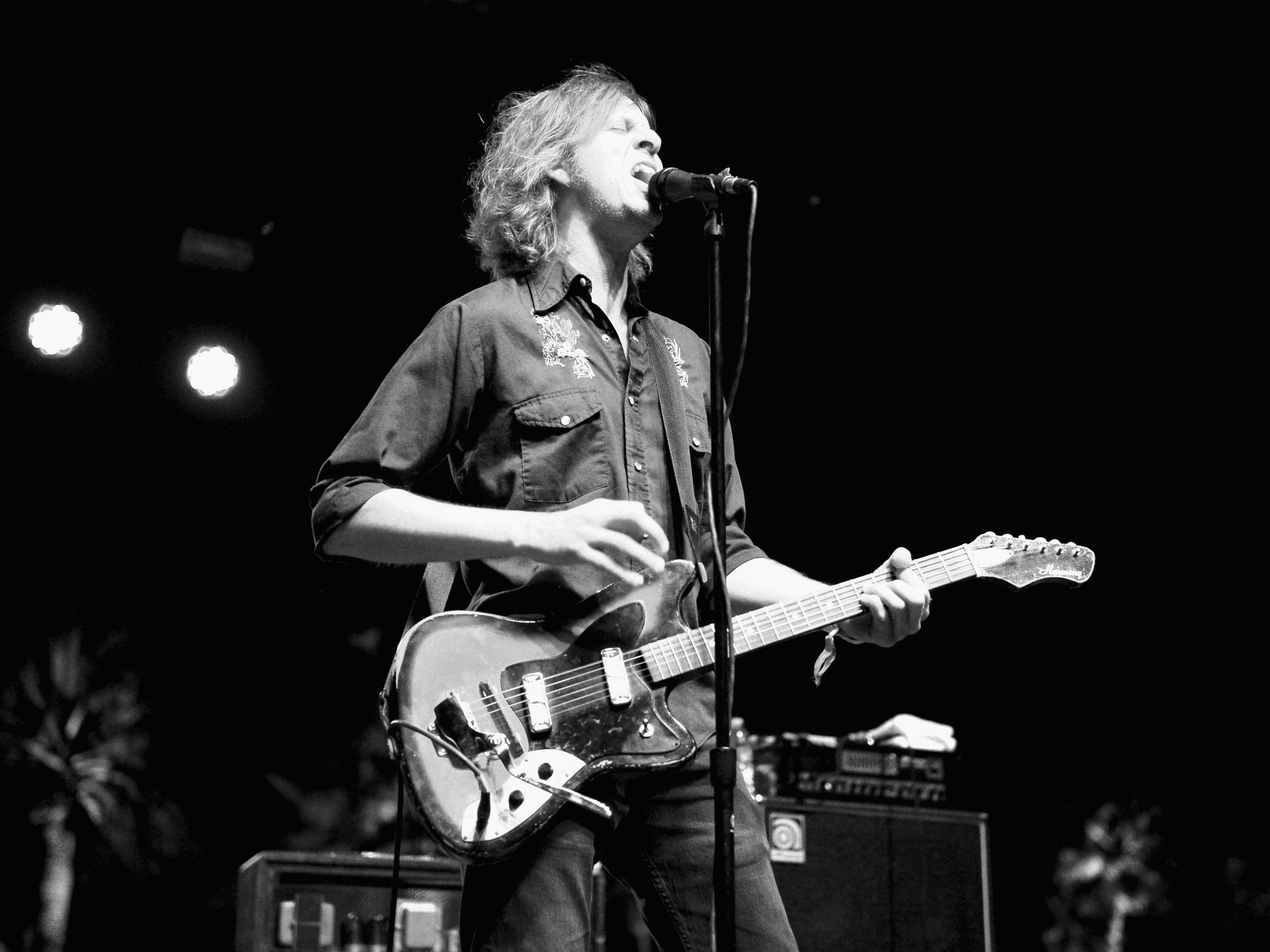

I was shocked to hear about the death of singer and guitarist Rick Froberg on June 30th, at the age of 55. In a decade of attempts to free the dissonance by dozens, or hundreds, of art-damaged rock bands, Drive Like Jehu were a beacon. Improbably tight, twinning guitars like a mesh, their sound is of an era and only themselves. Nobody plays like this, and many try.

Drive Like Jehu wrote epics, and the suite-like presentation of their songs seldom meanders; on longer tracks like ‘Luau’ or ‘If It Kills You,’ every twist and pivot is climactic. ‘If It Kills You’ opens with ear-scratching leads over a roiling bass, before the beat shifts for a driving instrumental section that both typifies and eludes the tropes of post-hardcore—chugging and dissonant guitars, screeching like irate gulls over a metallic sea. Feedback and melody, substance and skronk, are of a piece here, where guitarists Froberg and John Reis pursue a two-pronged, unified attack. On ‘Luau,’ the lead and rhythm are undifferentiated, even when they pry apart.

Drive Like Jehu is one of the great guitar bands of a decade, after all, making a precise riposte to butthead convention. After punk and heavy metal, rock guitar increasingly prefers the compact riff to the melodic phrase, flattening the relationship between chord and melody and leaving the vocal aside, as an expressive afterthought or rhythmic placement. By comparison, Reis and Froberg tend to loop odd melodic figures, creating a range of harmonic effects in addition to the often dissonant clusters of notes comprising each phrase.

Every bit as heavy as any of their contemporaries, Drive Like Jehu studiously decline the pentatonic readymades that make so much “noise” rock a boring drudge. Ambiguously voiced chords and bell-like harmonic motifs give the bass ample room to brood, above an accented, even choppy, drum. Where rock’s linear drive stalls upon the duplicable riff, Drive Like Jehu proffer the figure, a hypnotic eddy in the racing current. (This approach sours in “Midwest emo,” often attributed to Drive Like Jehu’s influence, where meandering arpeggios force melodicism into the template of rote riffage once more.) For all the density of this music, the lessons of minimalism apply.

These songs are tonally complex in another sense too, as concerns the obliquely menacing lyrics and Froberg’s desperate, baying voice. On either of their perfect albums, his gnomic language and throat-tearing delivery evades the lightly retouched lechery of Scratch Acid or The Jesus Lizard on one side, and the Kantian earnestness of Fugazi on the other; though these bands are kindred. The voice scares and consoles on these records, unerringly direct and ominously vague: "Learn to relax, if it kills you. You had your chance, hold on 'cause it's gone."

Plainly, there aren’t any bands to rival Drive Like Jehu at their searing best; but they made everybody better when they raised the bar. So thanks, Rick Froberg, for ‘Caress’; for ‘Atom Jack’; for ‘New Math’; ‘Bullet Train to Vegas’; ‘Paperwork’; ‘I Hate the Kids’; ‘No Hands’; the list goes on, at nowhere the length that I’d prefer. Forever.

PLAYLIST:

Dungbeetle - The Man Went Out

Pussy Galore - Evil Eye

Six Finger Satellite - Rabies (Baby's Got The)

Cop Shoot Cop - Nowhere

Drive Like Jehu - If It Kills You

Come - Off to One Side