Punk Against Apartheid

On BDS in DIY

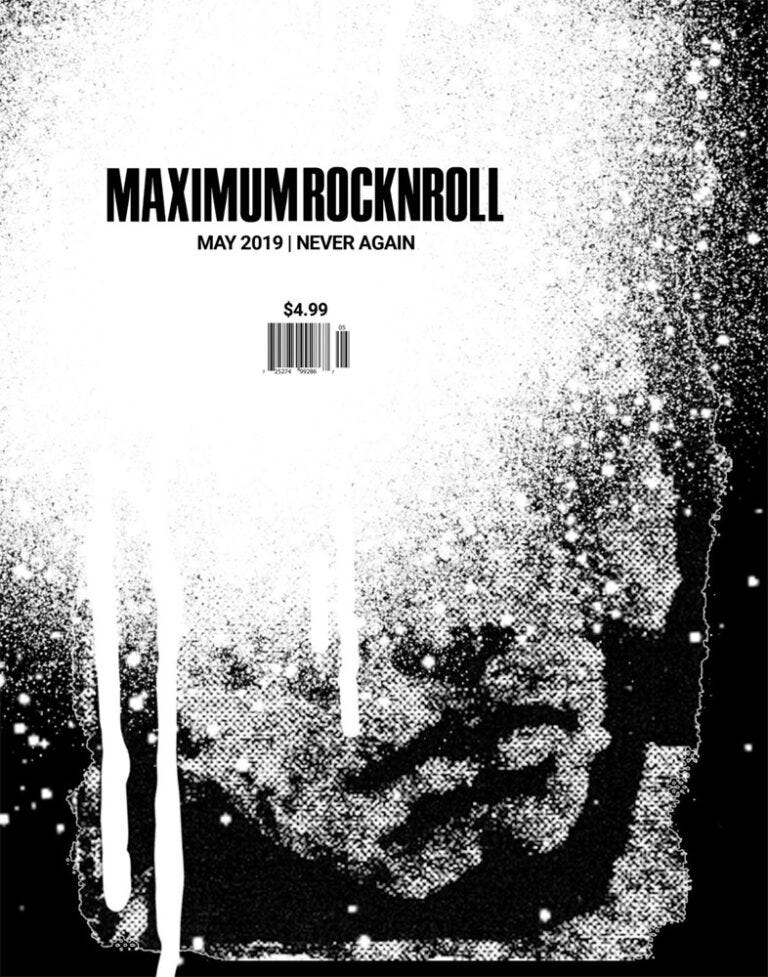

In May 2019, Maximum Rocknroll published its final print edition—the last chance for punks to dirty their fingers with fresh ink on newsprint, encapsulating decades of an essential resource. NEVER AGAIN, the cover declares, drawing a line from the post-WWII invigilation of collective human rights through the solemn aesthetic of Discharge and their followers. (The magazine cover effaces one of the group’s high-contrast icons, a distorted visage with hollowed eyes and pursed lips, apparently adapted from a collaged photo of the Pop Group’s Mark Stewart.)

It was a strong finish, with features on Chronophage, a current favourite band; an interview with Martin Sorrondeguy on radical pedagogy; a tribute to the great Bush Tetras; and a range of hyper-regionalist band profiles and scene reports, MRR’s bread and butter. One of these profiles in particular had been a long time coming, and controversial—namely, a spotlight on the Israel Punk Archive, collected by Barak Mayer, alongside an interview with dissident Israeli hardcore band Jarada.

Both features were prefaced by a lengthy statement of position by the MRR “shitworkers” themselves, summarizing months of intense discussion:

Recent readers of Maximum Rocknroll likely know that the pages of the magazine have, over the course of the past year, included an ongoing debate on whether the magazine should feature Israeli punk or punks. The debate emerged when MRR first announced that it would be running an Israeli scene report, and then later decided against doing so in solidarity with the Boycott, Divest, Sanctions (BDS) movement and in acknowledgement of the illegal and immoral Israeli occupation of Palestine. This issue has been a challenging one for the people involved with content at MRR as well as the punk scene more broadly. We at MRR are unified in our opposition to Israeli apartheid policies, yet we have had differences of opinion regarding how to best stand in solidarity with the Palestinian fight for self-determination. How can our humble punk fanzine best amplify voices—Palestinian, Israeli, or otherwise—that stand against Israeli settler colonialism, militarization, and racism?

Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) has been the strategy of choice for global solidarity with Palestinians since the campaign launch in 2005. Modelled on the international campaign against apartheid South Africa, BDS costs Israel countless billions of dollars in foreign investment and exports annually—an entirely peaceful protest of remarkable efficacy. As crucially, BDS has a strong cultural component. As campaign co-founder Omar Barghouti notes, “the cultural boycott aspect of BDS has been among the most fiercely debated, and not just in relation to the South Africa reference.”

Much of this debate misconstrues the parameters and intent of the boycott, or is stated in misleading terms. The campaign, some right-wing critics claim, is tantamount to “collective punishment” of liberal Israelis—a tasteless appropriation of a strictly legal term which properly denotes the kind of war crimes that Israel visits upon the people of Gaza each day. In a small masterpiece of pseudo-prudent fake concern, the pro-Zionist Anti-Defamation League insists that BDS “does not support constructive measures” towards peace; rather, its “anti-normalization” stance forbids “people-to-people exchanges” and other such unclear objectives, omitting state and market mediation altogether. But, as Barghouti clearly states, the call to boycott bears upon Israeli institutions, not individual artists and academics; except insofar as they work in and through sanctioned apparatuses.

What does this mean for the global punk scene, which participants often describe as a horizontal network of effective counter-institutions, or an alternative economy? “We believe that any international band traveling to Israel is acting in defiance of the Palestinian people’s stated demands,” says MRR: “BDS not only calls for a state of non-cooperation with the Israeli government and its economic and cultural interests, but also demands resistance to the normalization of the occupation.” That’s clear enough, where it’s simply impossible to partake of meagre, if feisty, DIY infrastructure without supporting the larger economies in which such voluntarism is involuntarily enmeshed. But what of punk as an alternative, “sub-,” culture remains? From MRR: “When it comes to DIY punk being produced by Israelis within Israel, the call for a cultural boycott is more fuzzy. Is including the voices of Israeli punks who espouse anti-occupation views or engage in anti-state politics still a violation of BDS demands?” It’s a sticky question, and the Israeli submission above seems to have been published in the absence of a clear consensus from the staff. For my part, I think not—but so much depends upon where and how one encounters this work of resistance.

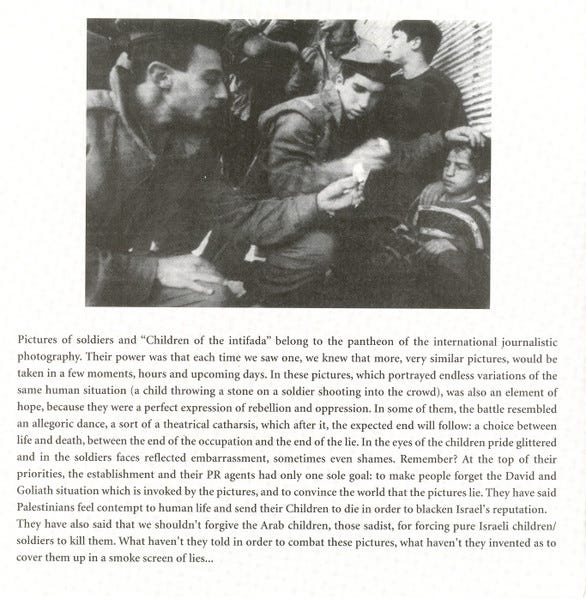

There is a formidable tradition of anti-Zionist punk in Israel, beginning slightly later than belligerent torchbearers Cholera, whose irreverence falls short of social concern. Noon Mem played peace punk in the late eighties, and their live cassette from 1990 is a low-fidelity, facetious collage, opening on martial snares and monologuing hip-hop before commencing a lengthy set of sinister punk sludge and two-chord stompers. (For what it’s worth, I would not have heard this music without the aforementioned archive). More significantly, Nekhei Naatza played frantic, provocative thrash from 1990 to 1997, touring the United States and releasing music internationally. Based out of Lehavot HaBashan, a kibbutz at the foot of the Golan Heights, Nekhei Naatza was stridently pro-Palestinian, attacking a range of Zionist opinion, from the “fascist left” to “Orthodox Jews with rottweilers.” Their only LP, הצדיעו למשטר החדש (Hail The New Regime), features a high-contrast black and white photo of Benjamin Netanyahu in a sieg-heiling salute: still suited to our moment even as the members of Nekhei Naatza belong to a generation radicalized during the First Intifada—self-styled race traitors more so than conscientious objectors.

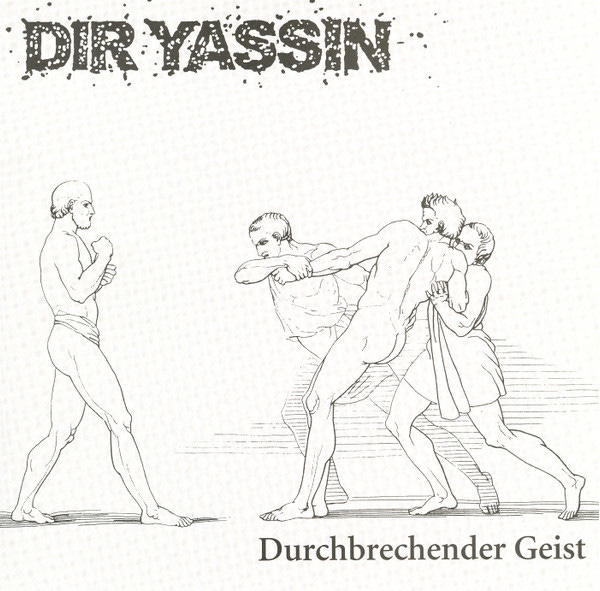

Nekhai Naatza ended after several members decided to move to Sweden and the United States, while those remaining in Israel went on to start one of the most significant Israeli hardcore bands of the next decade. Dir Yassin was named for the massacre of April 9, 1948, in which Zionist militias tore through an officially neutral village near Jerusalem and killed over two hundred residents before parading the survivors through the streets of the city on truck-beds. The inhabitants of Deir Yassin fought valiantly against the invading gangs, but the village was razed.

Several years later, ruins of Palestinian homes were incorporated into the structure of Kfar Shaul psychiatric hospital, warehousing Jewish Holocaust survivors and lost evangelicals under increasingly condemnable conditions. Israeli filmmaker and philosopher Udi Aloni’s 2006 film Forgiveness is set in this “borrowed village,” and pursues the local legend that “even nowadays, the Holocaust survivors hospitalized in Kfar Shaul communicate with the ghosts of the murdered inhabitants of that village.” Today, the name denotes both memorialization and return—Palestinian poet Samih al-Qasim achingly describes the awakening to life of “the first human on another planet called: Deir Yassin.”

Likewise, the band describes their name as a “positive provocation,” intended to push back against the perception of the massacre as an “isolated event” rather than a paradigm of occupation. In this capacity, Dir Yassin’s first offensive was against punk itself—as a predominantly apolitical re-expression of Israeli civil society and its norms.

There’s lots of kids that say: ‘I’ll have to join the army soon but until then, I’ll be a punk!’ When they get out after three years of Zionist brainwashing, it’s pretty clear that they won’t be punks anymore. That’s the main problem for the scene here. You’ll have hundreds of kids into punk, then they’ll go off to join the army at 18, never to be seen again. Then you’ll have a new wave of kids and the same thing will happen, it’s an endless cycle. So now the main thing we try to do is to convince people not to go to the army.

Here punk is posited directly against Zionism, such that the prospect of Zionist punk would be contradictory. But this polemical forcing is not so apparent to legions of conscripts: “There used to be all these people back in the day, they could sing ‘Bloody Revolutions’ by Crass by heart and they were singing it with their uniforms on and their guns around their shoulders.” In the same interview, the band recommends various means of avoiding the draft—either by profession of mental illness or anti-militarism. In this setting, stereotypical hardcore declarations of eternal youth assume a dire significance, where refusal to come of age also means a refusal to kill. For Dir Yassin, punk mustn’t be a phase but a resistant form of life.

Subculture itself doesn’t take care of this requirement. As the 2004 documentary Jericho’s Echo: Punk in the Holy Land demonstrates, punk accommodates a large variety of viewpoints, more often than not duplicating state ideology. “I think I need to go to the army and stay in my band and sing about the need for peace,” one young man says. Others describe their military attendance as a Monday-Friday job, killing for a living and living for the weekend. The far-right band Retribution is given ample time to espouse their views, which by their own account are perfectly expressed through the marauding IDF; and where service is mandatory, the terrifying presentation of such bands is more honest and less dissociative of surroundings.

Jericho’s Echo purports to turn its eye on an under-regarded scene, distant and ultimately relatable. But the fact that punk shows in squats and community centres look similar everywhere shouldn’t be so compelling, where even this informal infrastructure is nearly impossible to sustain across the carceral geography of the Occupied Territories. “We buy records, they don’t have food,” sing Nikmat Olalim—teenagers at the time of filming, whose anti-Zionist politics are represented on their half of a split with Scottish anarchists Oi Polloi.

The disaster of Israel forbids political quiescence, putting difficult questions to the punk scenes of other imperialist countries. How ought one to rebel as an unwilling beneficiary of unacceptable circumstances? And where all art is eventually nourished by its social and economic context, what support do we unwittingly extend to the regime beneath each band? What is the capacity of music for resistance? And should we reject the premise of punk’s autonomy, or the notion of alternative economy in general, is there any place from which to stand and declaim without incriminating oneself?

These questions, however, are often wielded as an argument against the cultural boycott of Israel in general. Why not boycott music from the United States or Canada, where artistic producers also stand in some expressive relation to colonialism and imperialism? This argument strikes me as disingenuous, because BDS is not a moral withdrawal undertaken on an individual basis. It is a coordinated, categorical campaign urged by nearly the entirety of Palestinian civil society, including labour unions, political parties, faith groups, refugee organizations; the list only grows, and were a similar campaign constructed elsewhere on this scale, artists in implicated countries would face some difficult decisions.

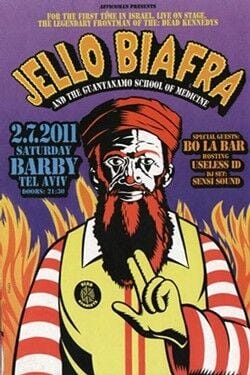

In 2011, the ad hoc group Punks Against Apartheid published an open letter to punk veteran Jello Biafra and his latest outfit, the Guantanamo School of Medicine, on the occasion of their decision to perform in Tel Aviv. The letter is lengthy, warm and solicitous, initiating a noteworthy public exchange between a luminary of US counterculture and the larger part of his global audience. “We are fans of yours,” the group begins: “There's no doubt that over the past 30 years, while so much of American culture has been inundated by cookie-cutter corporate pop, your words and music stood apart in calling out hypocrisy, corruption and oppression.”

In this spirit of sincerity, the Punks Against Apartheid letter pushes back at Biafra’s defence that "both the Israeli left and the Palestinian left are divided” as to the value of BDS tactics. Not only does the letter explain the breadth of the BDS call within Palestinian civil society and the diaspora alike, it reminds the reader and its famed recipient that the campaign “has now become a common topic in mainstream Israeli politics and media,” attracting widespread internal support. (Not mentioned in the letter is the corresponding call to Boycott from Within, which endorses the Palestinian call “as is” and moves to promote its aims within Israeli society.)

Biafra’s engagement ranged from defensive to empathetic, and the group eventually decided to cancel their appearance. In a 2012 article for Al Jazeera, Biafra detailed his subsequent visit to the region in a personal capacity; to see the reality for himself, as urged by the Punks Against Apartheid coalition, and to “get closer to some kind of conclusion on whether artists boycotting Israel … was really the best way to help the Palestinian people.” Naturally, Jello finds greater ambivalence about the boycott among Israeli punks than Palestinian activists, though in the end he reaffirms support for the campaign and its requirements: “I want to play. But I, too, am as sickened as the next person that not all the cool people I met in the West Bank can cross into Israel and enjoy Tel Aviv—or even worship in Jerusalem.”

Jello writes about the situation with decency, a great improvement on his earliest responses to the campaign, and his conscience, however “free thinking,” guides him to a position. In his response, Biafra speaks of the monumental expense of cancellation, but still inhabits a professional world in which these decisions can be framed as business. If anything, his wincing mention of the financial drawbacks is precisely to the point of the campaign; where there are gains to be had and losses to be incurred, the boycott is working. If you are the manager of an enterprise through which these measures may be seen to work, then you’re on the hook. If anything, Jello’s balance sheet ought to recall the extent to which punk, like any professional artistic activity, remains an essentially petty bourgeois pursuit.

As importantly, who is losing their shirt on these cancellations? Barby, the club where Jello Biafra and the Guantanamo School of Medicine were set to play, is one of Tel Aviv’s premier venues and a stronghold of cultural nationalism whose owner, Shaul Mizrachi, often finds himself defending his bottom-line against BDS. In spite of his professed apoliticism, Mizrachi “pampered” the IDF with Barby-branded “FUCK YOU WE’RE FROM ISRAEL” t-shirts during the 2014 Gaza War, in which more than 2000 Palestinians were killed. “Neither left nor right,” Mizrachi’s only public show of dissatisfaction with the actions of the Israeli government took place in 2020, when he went on a high-profile hunger strike in protest of COVID-related lockdowns.

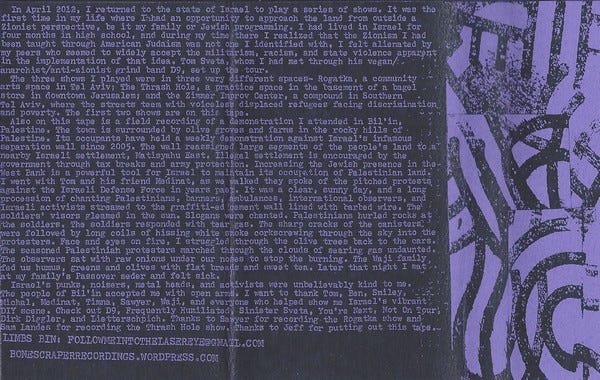

To what degree does DIY evade the snares of complicity that attend professional promotion? Nearer the ground, I think of Limbs Bin, the best and rarest noisecore act in the United States, whose 2012 “Live in Israel” cassette includes such disparate settings as an ecstatic live performance at an anarchist collective in Tel Aviv and participatory recordings of protest in Bil'in. The asymmetry of these documents maps onto the situation—where anti-Zionist Israeli punk nonetheless occurs in spaces furnished for dissident activity, and Palestinian resistance transpires in the open of life-and-death necessity. A corresponding tour journal contextualizes the sounds:

I watched pre-teen Palestinian boys dressed to the nines whip rocks at the faceless soldiers along the barren wall that separates the village from a near-by settlement. I ran through an olive orchard, mic in hand, as tear gas burned my skin, throat, and eyes. The Palestinians at the protest had all likely been imprisoned and faced far worse; lost family members, land, and any semblance of a clear vision of what a future Palestine would look like.

In Bil'in, the Wajji family offers hospitality to the protesters, while in Jerusalem, anarchist hosts regale their guest with stories of “tear gas, rubber bullets, shattered bones, Palestinian friends in jail, and fellow activists facing governmental legal abuse,” as well as the nitty-gritty details of draft-dodging, “from showing up to the draft meeting high on drugs to acting psychotic (Tom famously wore a snow suit and shivered through the mid-August interview).” Myths are dispelled and friends are made, and yet the dissonance is sickening.

Without giving way on BDS, which I support in every practical respect, it is precisely this kind of encounter that is lost amid total refusal. Neither is this simple: as Jennifer Lynn Kelly describes in her work on solidarity tourism in the Occupied Territories, expanded access to the West Bank is itself an outcome of the failed Oslo Accords, such that there’s no way to enter that doesn’t enrich the Israeli economy or entrench the region’s fractured administration. And yet, as I listen to this document of an educative internationalism such as punk rarely attains, I can sense the difficulty. Whilst necessarily intersecting the economy of apartheid, this “fraught anticolonial strategy” (Kelly) of firsthand visitation also has the potential to counter Israel’s own campaign to recruit artists, academics, and all manner of privileged guests to a white-washed and one-sided view of the occupation.

These examples concern the interaction of visiting artists with the Israeli punk scene, as recipients of hospitality and Träger of encouragement and capital alike. This is a different situation than MRR was still debating in May 2019, where the issue of visitation is presumed settled. Very well; but is it incorrect to listen to and to credit Israeli punk as it exists, even the anti-Zionist variety? Swedish anarchist and punk ethnographer Gabriel Kuhn stridently disagreed with this implication as it appeared in an earlier issue, penning an open letter to the magazine:

BDS is a political means to end Israeli occupation and to ensure the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination. This purpose must also be the guideline for its practical implementation. Now, it helps no one to isolate the forces that fight the policies of the state of Israel from within. These forces aren’t the most important ones in the struggle, they should not receive disproportionate attention, and their contradictions must not be romanticized away. But they are an important piece of the puzzle, just as white resistance against apartheid in South Africa was an important piece of the puzzle in the anti-apartheid struggle, and as the US-based movement against the war in Vietnam was an important piece of the puzzle in the defeat of the US military in Indochina. To cut such forces loose from an international resistance movement that is essential for sustaining them means to weaken this movement, not to strengthen it. This is also true in the case of Israelis who fight the occupation of Palestinian territories. The vast majority of Israeli punks belong to them.

Kuhn’s points are taken, where as per Barghouti, the boycott needn’t confront just any individuals—only those whose activities partake of Israeli state funding or sponsorship. In many cases, however, this may be too narrowly construed, where diffuse cultural apparatuses often serve to prop up the state by demonstrating its capacity for critique. Nowhere is this so glaringly true as in Israel, where music writer and sociologist Keith Kahn-Harris can read national pride from artworks of dissent: “Paradoxically, that this musical side of Israel can sometimes be highly antagonistic to Israel itself made me embrace the country more. A country that I can respect is one that has space for the cynics and the subversive—and it is usually they that make the best art.” (As Jello Biafra might say, “be patriotic, fight the government.”) What must punk do, if anything, to exempt itself from this agenda, where every sign of opposition is claimed for the state as an official dispensation?

This agency is difficult to locate and operates through many of our most intimate gestures, even and especially where we feel affinity. Recall how tellingly the ADL conceals its pro-apartheid agenda behind concerned solicitude for “people-to-people exchange,” as if this could transpire without political mediation, apart from those oppressive institutions that redouble difference as disparity. Even so, Israeli punk has produced a significant body of protest music, and it’s impossible for me to discredit Mitromemot’s dissonant, unfilial rage at Zionist social mores or Jarada’s frontline anthems against the Israeli state, including this year’s call to Tear Down the Settlements and Sentence Their Leaders. In their 2019 MRR interview, the band are clear enough as to their place in a global resistance:

We didn’t ask to be born here and we don’t like our reality as a part of an oppressing state, but we sure don’t stand aside and let it go by without trying to resist or help the ones in need … We know the gravity and the importance of these matters, and we’re the first reaching out to our buddies over the fence, at least as much as we can as private individuals against a monstrous machine.

Jarada understandably resent the implication that their proximity to the issue that most affects their lives should place their contributions on the side of reaction, regardless of content or quality. And I get it, where Jarada’s basically impeccable political hardcore compares favourably to all kinds of bonehead or trivial fare that gets a free ride in MRR and elsewhere. But a more decisive and strategic orientation towards this issue requires a rigorous economic geography of hardcore, one that can better locate the liberationist outliers of a justly embargoed Israeli scene. All told, until punk itself is a mass organization rather than a fair-trade marketplace, it will be difficult to connect the negative modality of BDS with positive support for anti-Zionist punks in Israel, or elsewhere.

So far, this concerns the navigation of punk geopolitics from a standpoint of support for the Palestinian people. But as the IDF advances a campaign of expressly genocidal violence in Gaza and a global movement amasses, it’s alarming to note the weak solidarity or outright hostility to this project by parts of the punk “scene.” This is no recent development, and MRR’s 2019 summary confronts the same problem: “Beyond our internal disagreements about how to best enact solidarity, these debates in the magazine revealed alarming swathes of mostly European punks who do not believe in solidarity with Palestinians at all, despite claiming to be anarchists or anti-racists.”

Today, the Punks Against Apartheid group that confronted Jello Biafra in 2012 is all but parodied in the newly formed Punks Against Antisemitism campaign, based out of Berlin. The location is noteworthy, where Germany’s queasy penance for the Holocaust—to say nothing of its incomplete de-Nazification, which ensured the long careers of many criminals—has produced any number of solemn memorializations and legal proscriptions that have been improperly wielded against Palestinians, while doing little to curb an actual fascist resurgence on the continent. Antisemitic incidents were on the rise across Europe and North America before October 2023, having nothing to do with the movement for Palestine but with an emboldened far-right; and yet Punks Against Antisemitism have formed to raise awareness of “Israel-related” antisemitism, which in their own words means opposition to the war on Gaza. By this admission, the coalition is based on a self-defeating premise; namely, the antisemitic canard that all Jewish people are signally linked to the political project of Israel, an assertion upon which only rank ethnocentrists, of sometimes inimical camps, agree.

What else? “As left radicals, we believe it is worth and allowed to criticize everything, including every government (yes, including the Israeli government!), the scene, we are part of and above all ourselves.” So what does accountability look like for these self-proclaimed “left radicals?” Their FAQ begins with what ought to be a softball question: “Is it possible to formulate a valid but not antisemitic critique of Israel’s siege of Gaza as an unjustified act of collective punishment that necessitates an immediate and permanent ceasefire?” Sure, the Punx reply, but they wouldn’t want you to think that they support a ceasefire:

Unfortunately, the second part of your question bears questionable assumptions. The war in Gaza is not ‘unjustified’: Hamas declared war on Israel—and Hamas currently rules Gaza … Israel is aiming to destroy Hamas, not the Palestinians. The devastating death toll of Palestinian civilians is due to the horrible tactics of Hamas and—in general—to the brutal logic of war.

In this cynical misattribution of the civilian death toll, rationalizing ethnic cleansing as collateral damage, it’s difficult to tell these “anti-state” educators from Likud. So much for criticism of every, “yes even the Israeli,” government. It isn’t necessarily surprising to see a section of anarchists drift to the hard right in war—recall Crimethinc’s detachment in Ukraine, which knowingly linked up with the neo-Nazi Azov Battalion—but the brazenness of this confession stops me cold. Germany has long grovelled before Israel, as if its government were synecdochally equipped to dispense forgiveness or cancel a moral debt on behalf of the Jewish people they falsely purport to represent; and this has produced one of the most stridently Zionist punk scenes anywhere outside of Israel. I recall stories of German “anti-fascists” disrupting appearances by the Black Hand, a Montreal-based metalcore band fronted by vocalist Radwan Moumneh, for their pan-Arabist politic. Here too, German anarchists are agents of the state, racist as they are righteous.

The Punks Against Antisemitism campaign clearly demonstrates that anarchists and punks throughout the imperialist bloc can be cultural ministers to the occupation too, and if punk is capable of mustering a political rather than economic boycott, it should unsparingly apply to these apologists and all the spaces in which they are permitted to work. Who are these collaborators, who carry water for the killers of 20,000 Gazans, and who dare attribute their lust for war to an enlightened anti-racism? Surely our collective response can sanction this as well.

It’s difficult to politicize culture where culture is politically subsumed, and this includes punk in spite of its attempted separatism. Here we should note a fundamental contradiction within the very premise of “international hardcore”—where the anarchist-inflected global punk scene often fails to attend to the geopolitical specificity of the scenes it would span by indifference. The paradox of anti-nationalist inter-nationalism culminates in an apparent irony, where we use states’ names to denote entire scenes that do not necessarily stand in transparent relation to state aims. After the challenge issued by bands such as Dir Yassin, is all good Israeli hardcore not anti-Israeli hardcore? Can punk negativity facilitate a properly political act of national abnegation? If so, how so, and if not, why not?

As we discuss whether and how to support Israeli bands fighting apartheid and occupation where they live, we mustn’t miss the more salient point that Palestinian punk mostly takes place in the diaspora for want of the state form that most punks cheaply disavow. Supporting Palestinians in punk wherever it occurs is far more pressing than coming to a one-size-fits-all verdict on Israeli participation, where Palestinian punk, as global cause or nodal scene, is in a state of becoming—and will continue to grow as a facet of the total liberation of the Palestinian people.

There’s a growing body of hardcore punk by Arab punk bands the worldover that we can support today, writing songs of rage and self-determination, mourning and resistance, that can focus our power as we move together. Pure Terror in New York; Mara'a Borkan and Khassarat from Tunisia, the latter by way of Montreal; Taqbir from Morocco, who are heading out on tour with a reunited Haram; and more. Check out the melancholic, raging crust of Inqirad, based in California:

لما كنت صغير لما كنت سبع اسنين

When I was young, when I was 7 years old

ايجاني ملك الموت

The Angel of Death came to me

قال إلي شو رح يسير في اسرائيل

And told me what will happen in Israel

ما صدقته

I didn't believe him

بس هو كان صحيح

But he was right

لما كنت صغير لما كنت عشر سنين

When I was young, when I was 10 years old

ايجاني ملك الموت

The Angel of Death came to me

قال إلي شو رح يسير بفلسطين

And told me what will happen in Palestine

صدقتو و متنا

I believed him and we died