The Metaphysical Detectives

Guilt, Grace, and Gaze in the World of Twin Peaks

In a 1948 essay, 'The Guilty Vicarage,' poet W. H. Auden confesses his addiction to the detective novel. “The symptoms of this are: Firstly, the intensity of the craving … Secondly, its specificity—the story must conform to certain formulas … And, thirdly, its immediacy. I forget the story as soon as I have finished it, and have no wish to read it again.” Because of the compulsive behaviour that such books encourage, Auden decides, they “have nothing to do with works of art.” No sooner has the poet declared literary disinterest in the genre, however, than he proceeds to redeem this vice in high Freudo-Anglican style:

The interest in the thriller is the ethical and eristic conflict between good and evil, between Us and Them. The interest in the study of a murderer is the observation, by the innocent many, of the sufferings of the guilty one. The interest in the detective story is the dialectic of innocence and guilt.

The standard murder mystery, Auden suggests, may be formalized as an allegory of the Biblical Fall. The format is straightforward enough: a closed community, unspoiled for being so, goes about its business, until a crime occurs that forces its participants to shed this illusion. Not only is the mythic innocence preceding banished by this irruptive, as yet unattributable, act; there also follows a suspenseful moment during which everyone must bear the moral repercussions equally. For as long as the identity and motive of the murderer remain unknown, guilt is distributed throughout the populace. Everyone appears a probable killer, albeit for their different reasons, all of which are plausible enough. At this point, redemption of the townsfolk, head by head and as a social whole, requires the assumption of guilt by an individual. By this time, however, the investigation will have shorn the townsfolk of their collectively professed innocence.

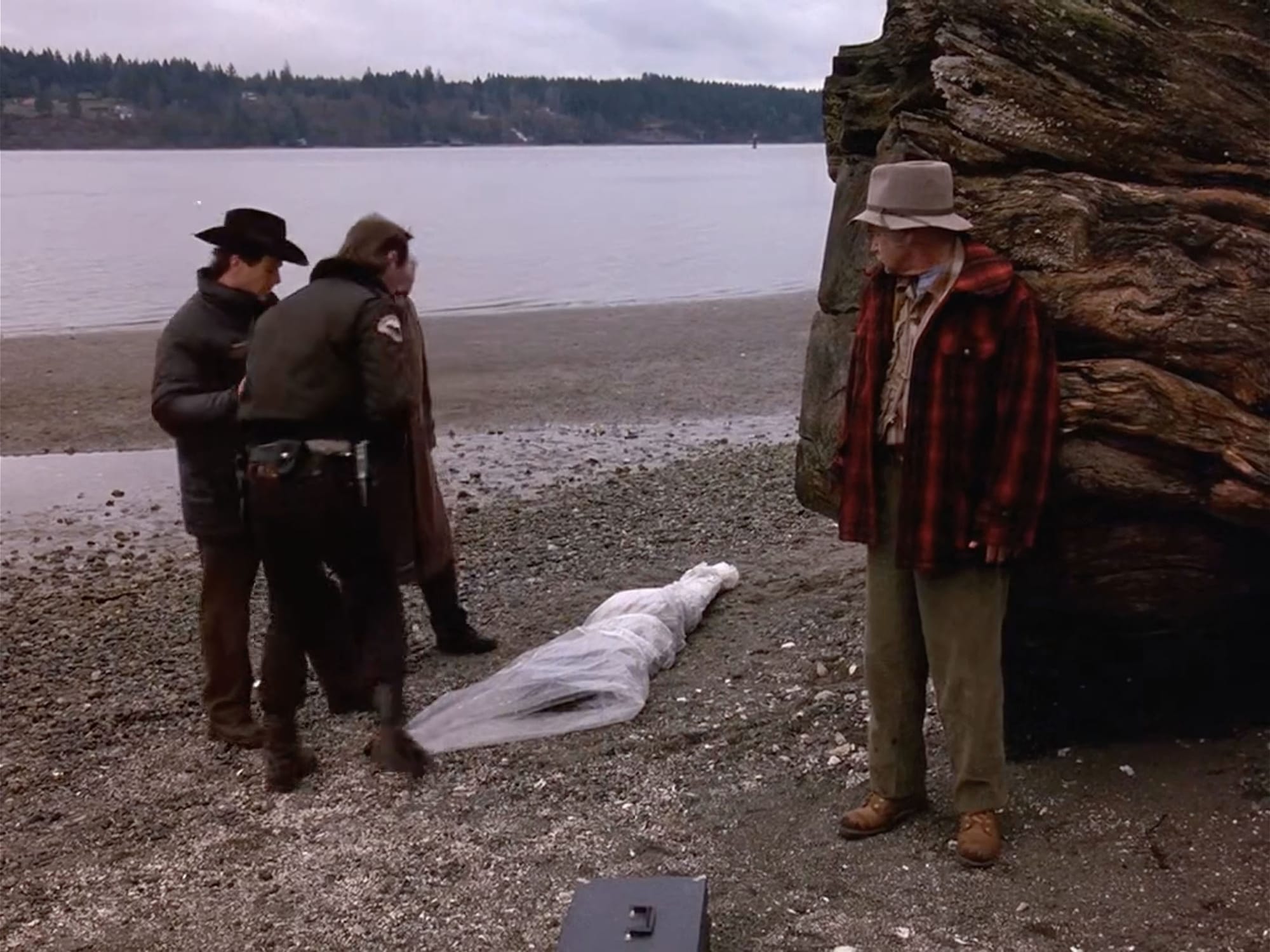

Who Killed Laura Palmer?

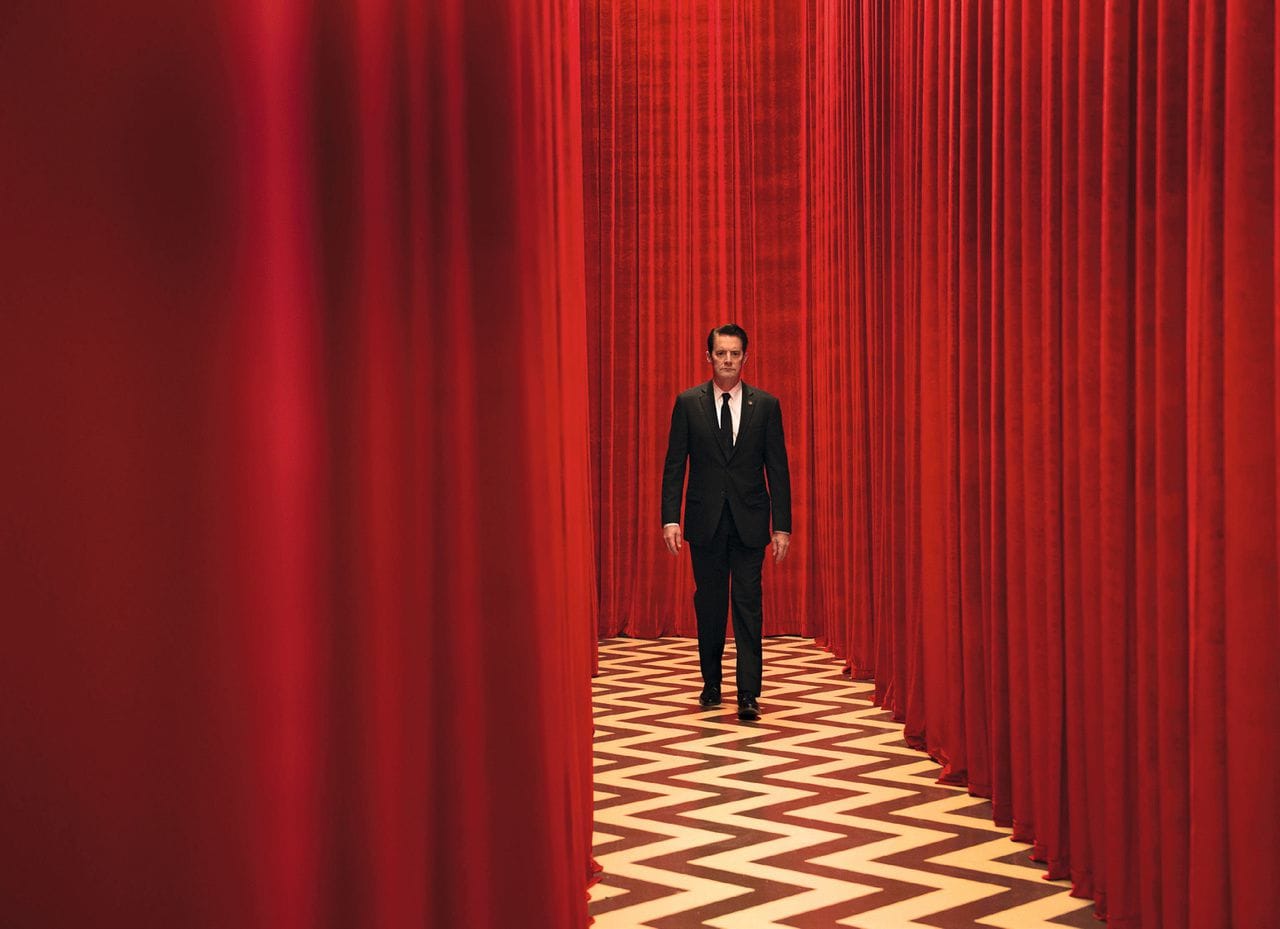

The television series Twin Peaks is set in the fictional town of Twin Peaks, a peripheral setting closely resembling Auden’s ideal village. Local affairs are broken by odd intimations of a world beyond: foreign investors in pursuit of business opportunities, or, as urgently, federal agents sent to investigate a murder. By the time of a viewer’s arrival on the scene, the entire situation of the show has crystallized around such a disturbance, and a corresponding question: Who Killed Laura Palmer? Defying procedural expectations, this question looms for a full season and a half, and perhaps longer: the killer’s ontological status remains uncertain, his power assured to exceed the lifespan of those he possesses. The question "Who Killed Laura Palmer?" indexes and conditions the social link in Twin Peaks. All of the township asks and is accused at once; and the investigation threatens to out any number of banal transgressions, as it confronts each individual with the necessity of being seen.

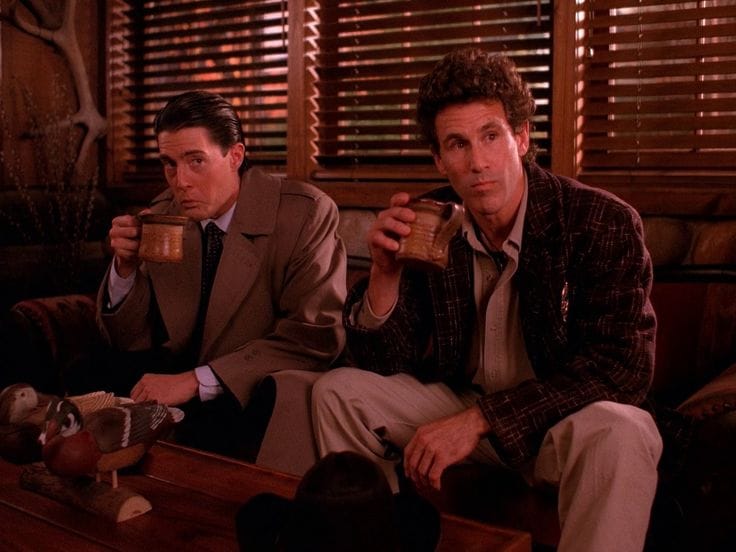

So how do we see the people of Twin Peaks? “The characters in a detective story [should be] eccentric (aesthetically interesting individuals) and good (instinctively ethical),” Auden reminds us, which precludes neither mischief nor malfeasance. One distinction of Twin Peaks is to permit its characters something more precious than innocence, which they are not, as no one is. Rather, Lynch's portraits afford the murder’s retinue the dignity of their desires. A soap-operatic intensity of scheming feeling drives the plot—more palpably joyful than the slow-burn bafflers later to be branded Lynchian—as the writers, Lynch and Frost most notably, manage by rapid juxtaposition to achieve a tone of unbearable levity. An infinitely transmutable evil stalks the woods, and yet this presence hardly distracts from the town’s daily, and adulterous, affairs.

These banal digressions furnish the show its trademark ambience; that of a dreamlike realism, a total confabulation in which each sign, however asinine, must be presumed articulate. There are two categories of object at hand here: red herrings and theatrical rifles, though the distinction between the two is only established in retrospect. This ambiguity spans airs of poignancy and menace, and produces the obsessiveness with which viewers of Twin Peaks swap trivia in the truest sense, as trivialities tempting future aggrandizement; or, to etymologize for a moment, as object-nodes that are themselves a crossroads between worlds.

Auden states that there are five elements to the detective story: “the milieu, the victim, the murderer, the suspects, the detectives.” The milieu we have discussed and will return upon: it is inventoried by the question "Who killed Laura Palmer?" Laura is the emblem of the show, fulfilling the contradictory requirements of literary victimhood put forth by Auden: “[She] has to involve everyone in suspicion, which requires that [she] be a bad character; and [she] has to make everyone feel guilty, which requires that [she] be a good character.” Of all the physical doubles that proliferate throughout the worlds of David Lynch, the most important are those pairs divergent in desire but identical in name and body.

The killer must be one who reserves the right of omnipotence, who is willing to transgress the most basic socially constructive prohibition. It's fitting that throughout Twin Peaks, debauched father figures abound, lurking behind closed doors, across the border, or beyond curtains. The suspects are “a society consisting of apparently innocent individuals, i.e., their aesthetic interest as individuals does not conflict with their ethical obligations to the universal. The murder is the act of disruption by which innocence is lost, and the individual and the law become opposed to each other.”

But the most important detail as it bears on Twin Peaks is the role of the detective, who represents an ethical ideal in contradistinction to the aesthetic turmoil of his or her surroundings. “In either case, the detective must be the total stranger who cannot possibly be involved in the crime; this excludes the local police and should, I think, exclude the detective who is a friend of one of the suspects.” This tension between the aesthetic and the ethical maps onto the contradiction between the salvific figure of the detective and the inertial, perhaps culpable, institution of the local police.

This convention demands the implacably wholesome Dale Cooper’s appearance in Twin Peaks, whose love affair with his newfound surroundings contradicts his allegorical bearings. If anything, his gradual integration into the life of the town foreshadows his decades-long arrest in nether-regions of reality. Put otherwise, Cooper defies the expectation that once the mystery is resolved and innocence restored, the law is supposed to retire.

This is precisely what does not happen after the close of the initial case, when Cooper is stripped of rank and plans to stay on as a resident in Twin Peaks, having become happily acclimated. Such contentment is an unsuitable development from the standpoint of the law, and Cooper’s retirement plans culminate in his captivity in the room beyond the woods. Much of the action, and the stalemate endured by viewers for two-and-a-half decades between seasons, proceeds from the false ending of the investigation by familiar standards. Innocence was not restored in customary fashion, but a sacrifice was nonetheless required.

Waiting Rooms

The time of the resurrection—of the event consummating the revelation—is that of a foreclosed-upon chronology, corresponding to an interval between two events, the latter of which will secure the meaning of the first. “I’ll see you again in 25 years,” Laura Palmer says to Dale Cooper in the final episode of season two, a quarter century before the anticipated return. By the time of The Return, Twin Peaks is no longer economized after the fashion of a television soap opera. Throughout the original run, resurrectionary time—a time for the kindling of belief in between two equally impossible events—was regulated from week to week by the serial form.

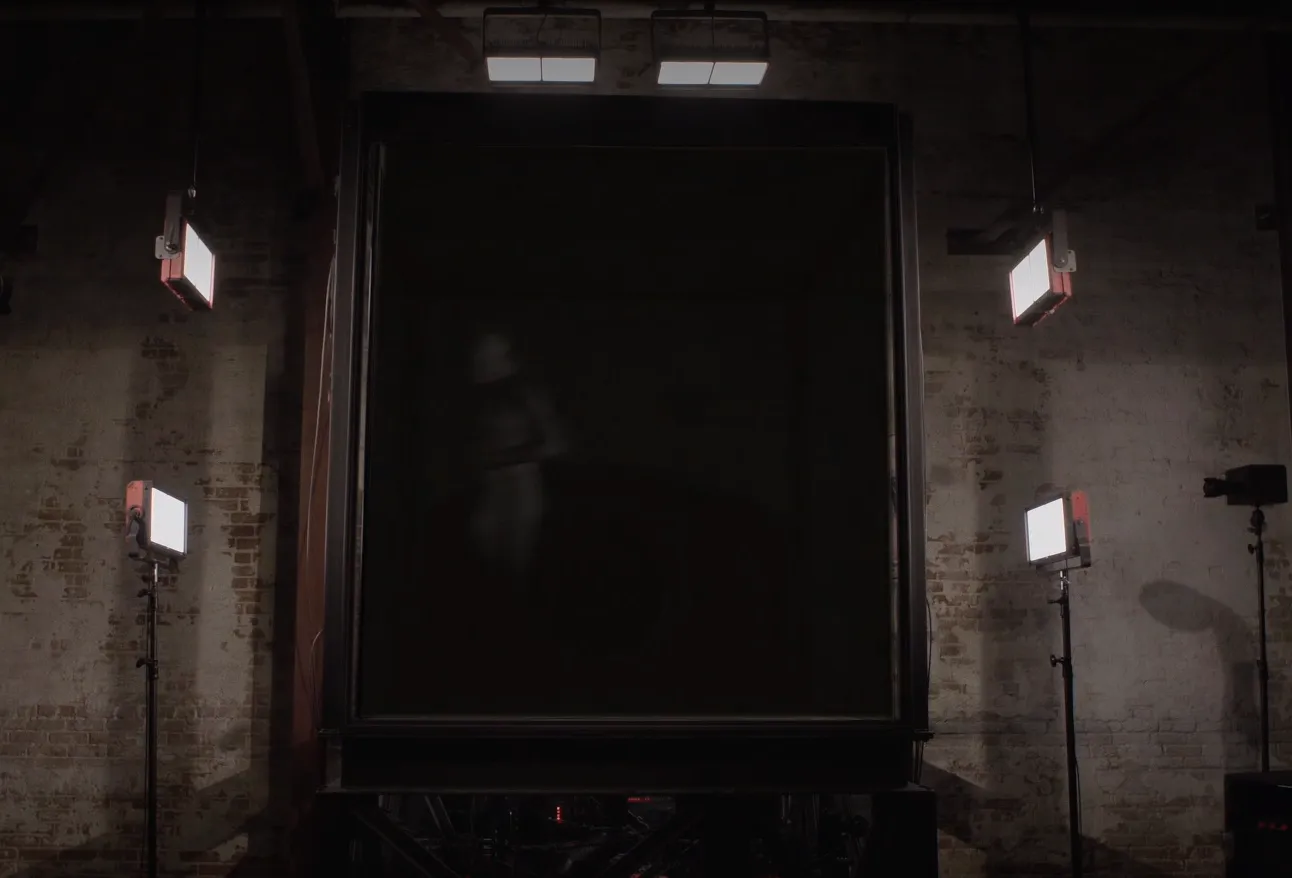

Twin Peaks: The Return is set in the time of waiting. Or rather, in a space of waiting properly called time. A young man sits in a concrete room watching for something, who knows what, to appear in a glass box before him. Elsewhere, the detective whose return ensures our interest sits placidly in an armchair, receiving counsel from the dead. As has become Lynch’s trademark over the intervening years, long takes and pregnant silence, all manner of visual and aural static, escalate to near-unbearable intensity by way of a viewer’s excessive interest.

Nothing becomes something before one’s eyes and ears, only to recede once more into the doubtful terrain of moot detailing. A lushly evocative soundscape enfolds what scant dialogue appears, as Lynch befuddles typically exclusive regimes of formal austerity and sensuous aestheticism. Angelo Badalamenti’s distinctive score, a character unto itself, arrives late to the scene, and in the meantime the viewer endures a feeling of emptiness in repletion, or the opposite: depth signifying lack.

Discoveries and Secrets

Deleuze and Guattari differentiate between literatures of secrecy and discovery, associating each of these modes with the novella and the tale respectively. This distinction has to do with temporal foreclosure, for the time of the novella is suspended in retrospect of a reader’s interest: “Everything is organized around the question, ‘What happened? Whatever could have happened?’” By contrast, the tale, however fatalistic—formulaic, even—impels the reader forward: “an altogether different question that the reader asks with bated breath: What is going to happen? Something is always going to happen, come to pass.”

Perhaps the seam between seasons one and two of Twin Peaks, still divisive of opinion, corresponds to this distinction. Season one addresses the township as so many pre-established secrecies. Season two, which resolves the initial mystery by episode nine and promptly devolves into a cat-and-mouse game between Dale Cooper and his nemesis Windom Earle, tempts its viewer with revelation after revelation. And much has been made of the 1991 finale, directed by David Lynch after a fourteen episode absence, which draws a veil of obtuse symbolism around an increasingly corny caper, restoring the plot to unbreachable secrecy.

Fire Walk With Me, a feature-length prequel released after the cancellation of the television show, is split down the middle in analogous fashion. Like Lynch’s Lost Highway, it is two more or less separate movies, abandoning an established plot mid-course never to return. The film deepens the mystery for the first third or so of its running time, before abruptly embarking on an over-vivid play-by-play of what we already know to have transpired, corresponding precisely to eyewitness accounts from the pilot episode. This sequence capitulates to the spectacular in its straightforward depiction of sexual violence, which otherwise remains on the side of the properly unrepresentable for much of the series.

Fire Walk With Me borrows the format of the television procedural, which typically begins with a graphic depiction of the crime, even revealing the identity of the perpetrator at the outset, only to let the detectives in on their established identity gradually throughout. The viewer is placed on the side of the villain as much as the detective, an idealized conflict that pardons the social element enveloping both . In this respect, the procedural reassuringly depicts a “mind-your business” ethic, assuring structural innocence. With the appearance of Windom Earle in Twin Peaks, the original series veers dangerously close to this motionless dualism, where no one’s position is importantly altered over the course of events. (Tellingly, the series uses the tired metaphor of a game of chess for the duration of their mutual antagonism.)

Auden’s ideal detective story is not marked apart from such tales of good-versus-evil for that it relativistically dispenses with these judgements; rather, for a suspenseful moment commensurate with the time of reading, these identifications are uncertain. Notably, one of Auden’s own requirements of the detective story is that one may forget the plot entirely upon completion, for in the end all is resolved without remainder.

Pending this relief, one proceeds deductively. “You will never know what just happened, or you will always know what is going to happen: these are the reasons for the reader’s two bated breaths, in the novella and the tale, respectively.” For Deleuze and Guattari, the novel integrates the two forms, novella and tale, “into the variation of its perpetual living present.” How novelistic is the world under discussion here? The present of Twin Peaks is belied by all manner of eerie phenomena, which allude to other times and spaces, and Cooper’s own divinatory means of detection concern this extra-literary reality. Deleuze makes a special example out of detective literature:

The detective novel is a particularly hybrid genre in this respect, since most often the something = X that has happened is on the order of a murder or theft, but exactly what it is that has happened remains to be discovered, and in the present determined by the model detective.

The “model detective” is the literary personality par excellence, for as a kind of divine interloper in a closed community, he is more a reader of the book in which he appears than a character. Cooper’s present collates multiple realities, and his character appears a crucial intervention in the detective genre and the novel form alike. Compare D.A. Miller’s work on the nineteenth century novel as an oblique expression of new regimes of governmentality:

Crucially, the novel organizes its world in a way that already restricts the pertinence of the police. Regularly including the topic of the police, the novel no less regularly sets it against other topics of surpassing interest—so that the centrality of what it puts at the center is established by holding the police to their place on the periphery.

This, adapting Auden’s terms, describes the difference between the fallen world of social realism and the punctured Eden of the detective story. Miller’s nineteenth century novel presumes panopticism: and the “closed circuit” of delinquent society portrayed by Dickens, for example, just as well describes life in Twin Peaks, or any other Eden. Here the detective is extraneous; his presence disturbs the town little more than the murder he is sent there to investigate. If anything, the murder of Laura Palmer threatens to upset the essentially delinquent character of the town’s social functioning. In the case of detective fiction, where a police investigation centres the plot,

its sheer intrusiveness posits a world whose normality has been hitherto defined as a matter of not needing the police or police-like detectives. The investigation repairs this normality, not only by solving the crime, but also, far more important, by withdrawing from what had been for an aberrant moment, its “scene.”

This well explains the omnipresence of police throughout the essentially secular bourgeois novel, whose limited jurisdiction attests to “the existence of other domains, formally lawless, outside and beyond its powers of supervision and detection.” Within the economy of the nineteenth-century novel, the supernatural and the police are already formally allied on account of their transcendent status.

Police in the Machine

In his essays on nineteenth-century literature, Joachim Kalka relates the fascination of Friedrich Schiller with the supernatural detective story, as well as the police motif more generally. Kalka compares two works of Schiller’s: The Ghost-Seer, a supernatural tale of conspiracy, and its proposed counterpart, a fragment entitled The Police. While The Ghost-Seer inventories a “vast machinery of deception,” The Police sublimates this paranoid feeling, offering a romantic view of state bureaucracy: “The fascinating thing about Schiller’s Police is that the whole mass of conspiratorial secrecy that in The Ghost-Seer is still on the dark side, the side of evil, has passed to the good apparatus of state order,” Kalka explains.

For Kalka, Schiller’s fragment preconfigures the crime novel; which genre, in his words, “tends to deify the detective and denigrate the police.” Twin Peaks certainly plays up this jurisdictional animus, which is ameliorated in the town of Twin Peaks by the mutual embrace of local law enforcement and the FBI. Cooper finds himself deputized over the course of a burgeoning friendship with the local sheriff, while the boorish obstinacy of Albert Rosenfield gives over to a stiff respect. Within genre conventions, this rapport denotes a synthesis of romantic individualism and romantic bureaucracy.

In this aspect, Twin Peaks offers a model of ethical life exceeding small town morality. Fire Walk With Me, on the other hand, retains the contradiction between outside investigators and local law enforcement as a limit. When Agent Desmond, an apparent protagonist, disappears without a trace, this represents the suppressive victory of the delinquent milieu over its exterior truth. Kalka presents Schiller in outline:

A vast amount of action must be handled, and it must be ensured that the spectator is not confused by the great variety of incidents and the number of characters. There must be a guiding thread that holds everything together … [the characters] must be connected to one another directly or through the surveillance of the police, and finally everything must resolve itself in the audience chamber of the Lieutenant of Police.— The true unity is given by the police.

In Schiller’s draft, the police recuse the populace of complication and gift them happiness. They are a transcendental institution, tasked with “unifying disparate realities.” At the start of The Return, this station has been abandoned. From panoramic shots of the New York skyline to the scrolling titles identifying each would-be suburban desert that appears, the conspiratorial coziness of Twin Peaks is blown open onto intimations of a cold globality. The police as a benevolent tool of surveillance, beholden to a socially concerned narrativist à la Schiller, are nebulized here, where the vertiginous panopsis of The Return concerns the absence of a central character or throughline.

The metaphysical police of Twin Peaks must be understood after this fashion, however difficult to square with the blameworthy and brutal institution of actually existing law enforcement. The relative racial homogeneity of the fictional setting is hardly coincidental where this suspension of disbelief is concerned, as a negative condition of the village setting. Once more, the village is a place of ritualized harmony between the aesthetic and the ethical, or individual will and general laws, to follow Auden closely. And to the extent that Twin Peaks depicts a peaceable relation between detective and police, and between police and township, this relationship must be sacrificially secured. Fredric Jameson finds these utopian desires at work in another detective serial, The Wire—even praising the collusory culture that evolves within a small team of detectives, closing ranks around individual outbursts:

The lonely private detective or committed police officer offers a familiar plot that goes back to romantic heroes and rebels (beginning, I suppose, with Milton’s Satan). Here, in this increasingly socialized and collective historical space, it slowly becomes clear that genuine revolt and resistance must take the form of a conspiratorial group, of a true collective.

Of course, the fraternal propensity of an actual police to falsify evidence, perpetrate violence, and protect their own from outside inquiry is far from a model of utopian social life but definitive of an irredeemable institution. Jameson’s proposed allegory squares badly with reality in this respect, but this “becoming-detective” of the police is not unrelated to the dialectic of aesthetic and ethical interest that Auden ascribes to the Miltonic village mystery. The law must learn love, as love must replace the law. As Auden concludes, the detective story relies upon “the phantasy of being restored to the Garden of Eden, to a state of innocence, where he may know love as love and not as the law. The driving force behind this daydream is the feeling of guilt, the cause of which is unknown to the dreamer. The phantasy of escape is the same, whether one explains the guilt in Christian, Freudian, or any other terms.”

Paradise Locked

In Freudian as well as Christian cultures, guilt originates the social contract. Consider Freud’s myth of the Primal Father, whose despotic whims resemble the omnipotent delusions of the murderer in Auden’s schematized detective novel. In Freud’s fantastic description, an egalitarian society is erected in the stead of this tyrannical figure upon dispatch, on the condition that henceforth, no one attempts to take his place. This accords with the Christian description of the “lawman” who arrives from without to restore innocence to the fold, and eerily suits the vision of Twin Peaks, where so many family patriarchs are passing avatars of a collectively repressed depravity. As psychoanalyst Joan Copjec writes, “society is installed under the banner of the son who signifies the father’s absence,” an observation easily transposed from Freudian to gnostic tones.

Book three of Paradise Lost begins with the following prose argument:

God sitting on his Throne sees Satan flying towards this world, then newly created; shews him to the Son who sat at his right hand foretells the success of Satan in perverting mankind; clears his own Justice and Wisdom from all imputation, having created Man free and able enough to have withstood his Tempter; yet declares his purpose of grace towards him, in regard he fell not of his own malice, as did Satan, but by him seduc’t.

In spite of the free will of the offenders, the eventuality of the offense is perceived by an omniscient God at the time of their creation. Even before Satan has alighted upon earth, the choice of sin is foreseeable, such that “the Son of God freely offers himself a Ransome for Man” in humanity’s infancy. At the outset of The Return, Cooper is held in a space between two worlds, a “false dissembler” at large in his stead. It could be that Cooper is on a simple hero’s journey; or one may observe a resurrectionary temporality, where an ontological debt precedes any ontic intrigue whatsoever. The a priori damnation of any Eden is a condition of being seen, therein or anywhere. The great corroborator of humankind’s agency would be the romantic hero Satan, waiting in the garden at the time of God’s creation.

Copjec describes another staple of detective fiction, the locked-room scenario, in which a corpse appears somewhere held to be unassailable, in a space to which no one has access, foreshadowing or following the example of a breached Eden. Here Copjec adapts Alfred Hitchcock’s example of a scene where two men are examining an automobile assembly line, marvelling at the perfection of its products, when suddenly a car door opens and a body drops out:

Once the complete process of the car’s production has been witnessed, “once the measures of the real are made tight, once a perimeter, a volume, is defined once and for all, there is nothing to lead one to suspect that when all is said and done,” some object will have completely escaped attention only later to be extracted from this space. So, if no hand on the assembly line has placed the corpse in the car, how is it possible for another hand to pull it out?

The Return stages at least three such scenarios, from very different viewpoints. A young man sits in a secure loft above the New York City skyline, watching a glass box for something to appear. In South Dakota, an inscrutable crime scene materializes like a puzzle in a locked apartment, covered in the fingerprints of a man who wasn’t there. Most strikingly, the Cooper-Jones body swap depicts the locked-room scenario from an unexpected vantage. Dougie Jones, meat decoy, responds to his materialization in the Black Lodge as if he were the corpse on the assembly line itself: “That’s weird,” he reports as he's whisked away.

The architecture of The Return may be described after the manner of what Copjec calls the “lonely room”: “office buildings late at night, in the early hours of the morning; abandoned warehouses; hotels mysteriously untrafficked; eerily empty corridors; these are the spaces that supplant the locked room.” Something is in the room that shouldn’t be there, but that something is the room itself. Evacuated of desire yet haunted, these are the chambers of secrecy that characterize the forerunner to detective fiction: namely supernatural horror, and its morally ambivalent relative, noir. Kalka makes this case for Schiller’s fiction, and as Auden suggests, the detective story is already a secular counterpart to the supernatural tale, where both secure normalcy by reference to an excess: a paranormalcy or impossible irruption.

Exceptions

For Auden, the detective story narrates a dialectical remediation of individual and society after such time as the two have entered into opposition. In this respect, though the detective story must be counterposed to the police narrative, Schiller appears to insist that the latter (non)genre is absolutely prior, as it (negatively) constitutes the order to be disturbed. Miller’s agreement is logical, not genealogical: “Historically, it would be absurd to derive the novel from the detective story, whose ‘classical’ period of development neither precedes nor even coincides with the novel’s own.

More accurately, the detective story first emerges as an aborted function within the novel,” one that exceptionalizes the role of the detective in order to establish lateral relations of guiltless scrutiny. Copjec observes that the suppression or dispatch of the Primal Father inaugurates a culture of benign surveillance, which describes the closed society of the novel in Miller’s Foucauldian study. Problems of political modernity—which is to say, of constitutive enumeration— resound throughout the genre of detective fiction “which, classically, begins with an amorphous and diverse collection of characters and ends with a fully constituted group.” Political identity, says Jacques- Alain Miller, as the formal self-identity of the citizen, is necessarily sutured by reference to an excluded element. Likewise, writes Copjec,

The group forming around the corpse in detective fiction is of this modern sort; it is logically “sustained through nothing but itself.” The best proof of this, the most telling sign, is the fiction’s foregrounding display of the performative: in classical detective fiction it is the narrative of the investigation that produces the narrative of the crime.

This describes the scenario of Twin Peaks, as a self-reflexive instance of the detective story. The question "Who Killed Laura Palmer?" inventories the characters of Twin Peaks, whose mischief is of equal interest to the murder. What conveys so many isolated trysts and transgressions to one another, however, is their possible relation to a master signifier that at no point appears. “Laura,” one suspect whispers furtively, as another screams grief stricken. This invocation binds the whole, in the absence of the thing it names. “But if the relations among the suspects are differential,” Copjec asks, “what then is their relation to the corpse?”

At this point, content inculpates structure. Twin Peaks, like Blue Velvet before, appears to relish its depictions of violence against women. By depicting violence, an author lazily conveys to the viewer that the perpetrator is irredeemable, thus may be sacrificed with relish and impunity. Leo Johnson is a pariah of this type; as is Frank Booth, or Richard Horne. The moralizing double transgression of the revenge motif can only operate within an economy of jouissance. In any case, one must assume responsibility for the depiction in its originality: once more, the narrative of the investigation produces the crime.

That is, the retelling produces a group, which it consolidates only insofar as a final signifier is missing. This condition, says Copjec, underwrites detective fiction as well as romantic devotional, since the absence of this final signifier, securing all that came before, is also the cause for which there is no sexual relationship:

This signifier, if it existed, would be the signifier for woman. As anyone with even a passing acquaintance with the genre knows, the absence of this signifier is evident in detective fiction not only in the nontotalizable space that produces the paradox of the locked room but also in the unfailing exclusion of the sexual relation. The detective is structurally forbidden any involvement with a woman.

The courtly soap opera of Twin Peaks renders this prohibition heavy-handedly, where Cooper’s undoing as a chaste ascetic follows his self-described lapses of judgement in love. Cooper is lured to the Dark Lodge in pursuit of Annie, just after counseling Sheriff Truman back from the brink of madness, having fallen in love with a conspirator against him. As seen, in the traditional fraternal culture of the detective story, love inculpates the detective in the delinquent element from which he must be subtracted for the plot to hold together.

From a different angle, Jacqueline Rose discusses the anxiety that attends the appearance of a female detective, whose process of deduction produces a paranoid excess of criminal conspirators. This paranoia corresponds to a heightened cinematic awareness of the body of a woman, “reduced to the question of … what is at stake in constituting her as the object (and subject) of the look.” The female detective’s attunement to a generalized obscenity is her unique credential, exemplified by the character of Diane throughout The Return, whose contempt for a bureaucratic law enforcement agency that has not only failed to protect her but even sheltered her assailants places her beyond jurisdiction.

Throughout the first two seasons, Diane exists in name only, as the ubiquitous addressee of Cooper’s daily monologue. This invisible role corresponds to the generic veneration of the beloved in courtly literature, and it is after this idealized distance that one should understand her traumatic encounter with Cooper’s rapacious double, and her ambivalent reunion with a more temperate detective in the bleak finale. Diane’s own violent subtraction from the plot, not to mention her eyeless captivity in the body of another, attest to a well-established structure.

The motivational signifier “Diane” operates without referent, as a range of formal effects that contradict her assertions of subjectivity. When Lacan stated provocatively that “la femme n’existe pas,” he surely meant to demonstrate something like the difference between the “Diane” of microcassette and the Diane of her own desires, at large in the world during an uncounted interim. Most notably, the character’s articulate refrain, “fuck you, Gordon” is addressed to the character of Deputy Director Cole, played by Lynch himself.

Cooper’s love, like his reluctance to leave the town of Twin Peaks, proves fatal to his vocation as detective, which also happens to name the genre that Twin Peaks surpasses and perfects. The hackneyed antagonism between Windom Earle and Dale Cooper (Moriarty and Holmes) is compressed into and foreshadows an important structural coincidence more typical of noir; the ultimate identity of the detective and his or her quarry. Copjec describes how, as a function of the forbidden signifier binding the plot, pace is regulated by a “revolving door” dynamic, such that the detective and his or her other cannot occupy the same space. This structures the noir subgenre in particular, wherein detection proceeds on the basis of identification: “it is argued that the detective comes to identify more and more closely with his criminal adversary until, at the end of the noir cycle, he has become the criminal himself."

There is No Double of the Double

Such a fate befalls Dale Cooper too, whose blameless integrity as a character is visually secured by a physical double throughout The Return. Two Coopers, one good and the other evil, sounds simplistic, but Lynch knows when more is better. The True Cooper only partially re-enters the world in the shape of Dougie Jones, a third likeness and hapless cipher. This ridiculous figure triangulates the good-versus-evil dualism of the doppelgänger motif. What, as an illogical excrescence, does the appearance of a “third double” mean?

Dougie Jones is a fleshly medium, shorn of guilt and awareness alike, enacting a childlike innocence that the double typically protects. In The Double: A Psychoanalytic Study, psychoanalyst Otto Rank speculates that this psychic projection originates from a desire for immortality. As for the later bearing of this omnipotent double upon its mortal likeness, Freud notes the irony that any figure meant to extend one’s life is likely to be greeted as a deathlike omen.

The proliferation of doppelgängers throughout Lynch’s filmography, and Twin Peaks especially, corroborates this feeling of dread. Otherwise, to resume a television series twenty-five years after its last episode makes every character a double of their past self in a real sense. But the recurrence of familiar faces must be read alongside the repetition of any number of other details: “Finally there is the constant recurrence of the same thing, the repetition of the same facial features, the same characters, the same destinies, the same misdeeds, even the same names, through successive generations.”

Freud’s description of the uncanny double bears strikingly on Lynch’s intervention in the detective genre, where the nightmarish return of the same corresponds to the constricting lineages constitutive of a too-familial small-town milieu. Furthermore, the structure of the detective story depends upon everybody being possibly other than they seem. For as long as the crime remains unsolved, every person must be regarded as an unreliable double of their would-be criminal equivalent. Early in The Return, Bill Hastings, a mild-mannered school principal, is not only unable to convince his wife that he is innocent of a grisly murder; he appears unable to entirely convince himself. Hastings sees himself as we see him, as an object of suspicion.

Lynch’s films are themselves conjoined on the basis of eerie resemblances, where visual quotations accrue to an obsessional insistence. In addition to the inanimate cameos comprising his mise-en-scène, Lynch keeps the same stable of actors on retainer, exploiting the overdetermination of familiar faces with a keen understanding of cinematic transference. This is a formal postulate of film noir, which produces pangs of betrayal in a viewer by placing a face typecast “heroic” in seedy straits, and Lynch appears to savour the discomfort of attachment developed over the course of a career.

Across recurrences, The Return summarizes not only the world of Twin Peaks, but all Lynchiana, suggesting that his long-term viewer has never left that world. The northwestern “vicarage” of Twin Peaks is situated as a kind of diorama in a fictional America, encompassing the California of Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive, and Inland Empire as well as the New York and South Dakota of The Return. As the affairs of a township are counterposed to those of a country far exceeding any panoramic overview in its logistical and supernatural extension, a viewer must concede the genre of detective story to its fallen equivalent, noir; which is to abandon any belief whatsoever in innocence; which postulates the integrity of a garden somewhere, or a correspondingly benign civic.

Private Gardens

Innocence is only ever fantastically secured, and typically borrowed at that. As Geoff Bil demonstrates, the scenery and symbolism of Twin Peaks is rife with appropriated and misplaced imagery associated with Indigenous North American culture, and its metaphysical underpinnings rely heavily upon colonial tropes. As Bil emphasizes, Annie Blackburn’s environmentalist speech against the Ghostwood development draws on Chief Seeathl’s partially apocryphal address upon the surrender of land in 1854. Though misquoted, this speech exacerbates the stakes of the village mystery; for not only does the proposed development stand in contradiction to Annie’s holistic worldview, the entire town in its placement is thus transcendentally suppressive. There is no pending re-unity, no cathartic unveiling of localizable guilt, because the garden society in its fictive unity remains a violent culprit.

Where the relation of Twin Peaks to colonialism is concerned, Lynch employs many Western tropes alongside those of the detective story, similarly metaphysicalizing the frontiers upon which the genre depends. The peripheral setting of the Western depends upon a contrastive threshold, in order that a romantic (or Satanic) outlier may pursue their own redemptive purposes. In this respect, the Western inverts the values of the detective story: rather than a romantic detective- interloper redeeming a closed society, a prodigal figure proves the disunity of an uneasy social unity. This all-American genre presumes hypocrisy of its mercenary actors, and its colonial bad faith consists as much in the fallenness that it depicts as in its racist caricatures.

The Return is set in an atonal world, a world without a master signifier. And this signifier is strikingly not Laura Palmer in this case, but the detective Dale Cooper himself. For the avid viewer, his disappearance creates a traumatic rend in a familiar setting. Cooper’s bodily multiplication illustrates as much, and the expanded geography of the television show mirrors this vertiginous worldlessness. Quite literally, Cooper has been established as both an object of sacrifice qua criminal excrescence and the agent of deliverance qua detective, who is always and necessarily newly arrived on the scene.

For the residents of Twin Peaks circa The Return, the mention of Cooper’s name is greeted with slow or stoical recollection. They do not know what has befallen him, but nonetheless experience an emptiness or lack. The Log Lady offers Hawk as much: “something is missing and you have to find it.” That something is perhaps less purloined than misplaced, while a surfeit of incompatible theories prevents the viewer from discovering a message already in receipt.

Very quickly, The Return becomes a show about the time of watching Twin Peaks. For all of their withholding silences, Lynch and Frost stage reunion after reunion with a lunatic generosity, resolving decades old affairs with real feeling. Blurring digital video art and lush photography, Lynch enacts physical violence upon the image rather than the actor, who is more likely to vanish from the screen upon expiry than to mime the throes of death. And the younger generation that congregates inside the roadhouse may as well be gathered at their TV sets, thrilled to participate in so venerable an institution.

When Cooper reappears to rescue Laura once and for all, traveling through time to lead her away from the scene of her own murder, he understands his action to endanger everyone’s consistency, and warns his friends as much: “There are some things that will change. The past dictates the future.” By resolving the mystery in advance, Cooper revokes the condition that constitutes the fictional town. Leading Laura through the woods and away from the scene of the crime, Cooper assumes an Orphic figure, whose sin is reminiscence rather than hindsight per se. Cooper has Laura too much in mind, and when the finale depicts her likeness in a state of poverty-stricken purgatory, it becomes clear that his attempt to surgically alter events has failed in retrospect of our fascinated viewership.

In “Laura’s” final scream, Lynch issues an incredible thesis as to the self-referential reality of trauma, which doesn’t require the authorization of an original event. As Lacan remarks, repression and the return of the repressed coincide. Cooper has ventured back in time, eradicating the symbolic basis of the world in which he has been living, of which the viewer is an only witness. The last sound that reverberates is an affective remainder of an experience that has narratively revoked, such that it can no longer be addressed.

The Guilty Vicarage

Many of Auden’s observations from 'The Guilty Vicarage' are echoed in a passage from the poem 'New Year’s Letter,' to reiterate his thesis briefly in rhyme:

Delayed in the democracies

By departmental vanities,

The rival sergeants run about

But more to squabble than find out,

Yet where the Force has been cut down

To one inspector dressed in brown,

He makes the murderer whom he pleases

And all investigation ceases.

Yet our equipment all the time

Extends the area of the crime

Until the guilt is everywhere,

And more and more we are aware,

However miserable may be

Our parish of immediacy,

How small it is, how, far beyond,

Ubiquitous within the bond

Of an impoverishing sky,

Vast spiritual disorders lie.

The passage is apt, but the organization of Twin Peaks, as a mystery that mustn’t be solved, accords as well with a better known and considerably less anxious poem by Auden, 'Musée des Beaux Arts'—an ekphrastic commentary on Pieter Brueghel’s painting 'The Fall of Icarus,' in which Auden finds the “human position” of suffering affirmed as something daily and horizonal, no cause for which to skip one’s morning coffee. Brueghel’s propensity to embed catastrophic narrative detail in a teeming and indifferent landscape is pertinent. Think of the opening credits to Twin Peaks, surveying a natural sublime to dwarf the human scale of melodrama, even as the landscape gathers around an all-too-human, missing detail. In Twin Peaks, “everything turns away quite leisurely from the disaster,” because the disaster is the condition of indifference itself. It is this barely perceptible rend, occasioning the morbidity of the gaze, that Lynch directs over and over again.

Of course this composition has a name, one that the trees whisper, one from which everything proceeds; and the failure of this binding detail to appear is both a limit to interpretation, let alone enjoyment, and the enabling condition of both. As Lynch withholds this term to set a world in motion, he invites us to consider the cosmology of fallenness that underwrites any fantasy of repair. But until that indefinitely delayed reunion, our viewership continues to attend these scenes of trauma as a kind of church; which is to acknowledge a certain guilty interest in the first place.

This essay appears in The Vanishing Signs, published by ARP Books.

RIP David Lynch.