The Work of Moving People

RIP Phill Niblock

It’s almost impossible for me to imagine contemporary music without the presence and influence of Phill Niblock, whose glacial, unmetered drones carried the lessons of minimalism to submersive extremes for more than half a century. Whether composing for flute or guitar, organ or hurdy gurdy, Niblock made scalable monoliths, in which the slightest modifications produce vertical towers of tone.

But Niblock was more than a great composer. He was also a consummate placemaker, who offered his Soho loft to hundreds of performances by multiple successive generations of experimental musicians. In some of my fondest memories, I’m sitting cross-legged on the floor of Experimental Intermedia, oblivious to temperature and season, spine curled in attention. Sometimes my interest in the room itself would break my focus, and my mind would wander from the endless music to its personal occasions; all of the many bodies to have passed through this continuously lived-in space, the last outpost of a kind.

Likewise, I remember the marathon events for winter solstice—more recently held at Roulette—where a separately rapt, perdurable crowd would bask in Niblock’s commanding music for hours at a time; better to set aside the whole evening. The sound was always immense, an endless crescendo rather than a slow build, and might have tended soporific were it not for the wealth of visual information lighting the room. As notably, where so much drone music tends to pre-fab transcendentalism—sheer physical presence negating any musical society—Niblock’s richly layered pieces stood widely apart. However modestly, his work sought to explore the terms of its perception, and to facilitate experience of space.

It may seem strange to claim liveness for this music, where Niblock’s in-person appearances substantially relied upon pre-recordings; but his timbral investigations defy the conception of music as so many personal decisions, indexed to the physical presence of performers. Rather, these sustained sounds test the architecture of reception, where attendance is constructive and eventfulness a common goal. Nobody comes to watch the artist labour, a task already expended in the composition; we come in contribution to the hour’s work.

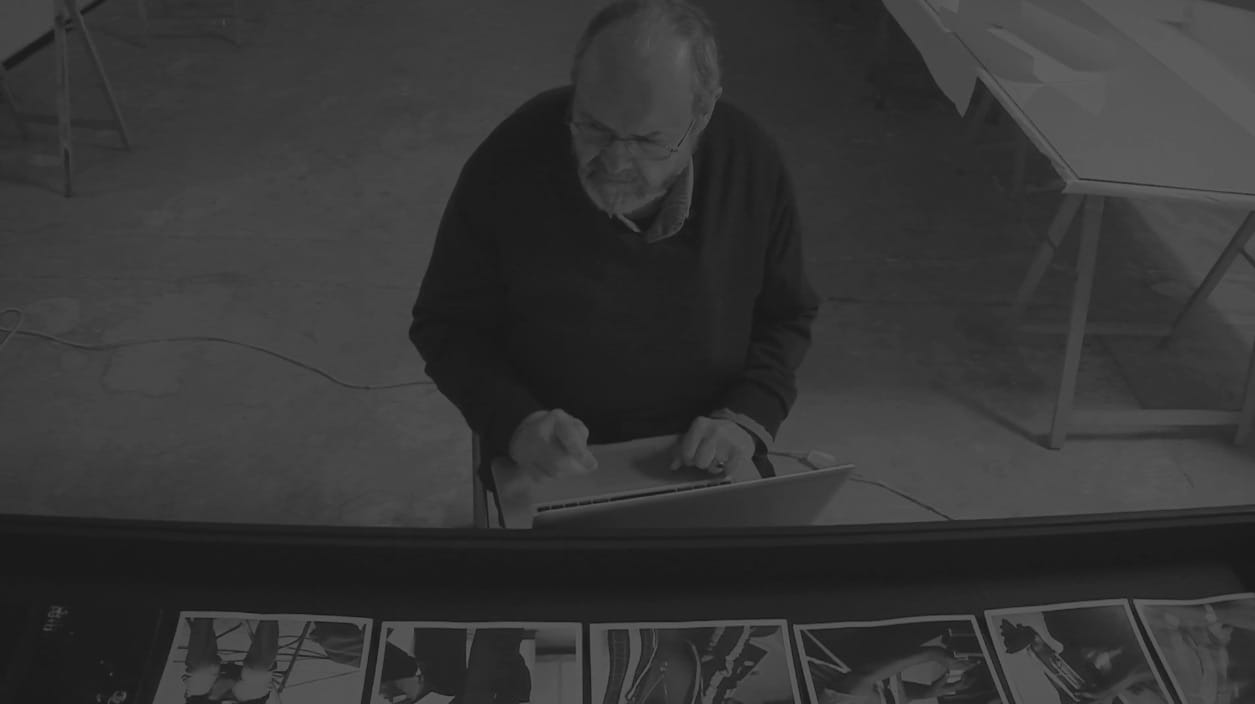

This concert dynamic is a fascinating complement to Niblock’s visual output, encapsulated by his ambient epic The Movement of People Working. Filmed between 1973 and 1985 in locations from China to Brazil, the countless hours of footage are typically presented as a multi-channel video installation, juxtaposing patient, fascinated footage of human labour in situ. Both humanistic and afflicted with an interloper’s sense of strangeness, these films depict the capacity of repetitive action to transform material reality, whether by fishing, weaving, cooking, harvesting, or other needful work. In this respect, The Movement of People Working functions as a minimal documentary, sourcing extravagance from utility and proposing an excess of choreography to consist in the everyday.

Screened simultaneously in a performance setting, however, the contrasting sceneries offer a spatial analysis of global capitalism, where a multi-rhythmic or bifocal imaging portrays complex divisions of labour. And where Niblock’s interest in a wide variety of productively deployed, culturally embedded gestures is principally rhythmic (“very much dance film, not ethnographic or political in any way”), the timeless stasis of his soundtrack assumes striking significance, as an aural representation of the abstract totality in which these disparate activities are enmeshed.

Niblock’s carefully observed social aesthetics facilitate such an interpretation, where the aptness of sound to abstraction permits us to approach the unrepresentable as a medium of experience. And while the artist himself was far too politically demure to make such claims, it speaks to the vastness and the specificity of his project that such a map would nonetheless appear, as if an etching of external circumstance on the aesthetic mind. These are only some of the places one might wander in the dark, and the solstice concerts were truly special—a multisensory summit of Niblock’s career, collecting decades of work in a spirit of playfulness and hospitality.

Perhaps I’ll leave it at this word, where the scenes and sounds that Phill Niblock created are the basis for so much of what we do here that it’s hard to summarize. In style and ethic, he and XI should name an era. Here’s to that legacy, endless as the music that we celebrate today.

Israel’s Drone Age

For Canadian Dimension, I wrote about Israel's assassinations by drone and the era of aerial state terror:

The failure to differentiate between combatants and civilians, and the transformation of all civic space into a potential and contractible warzone, are defining features of Israel’s experiment in government by terror, and terror by drone. In Gaza, where every one of the IDF’s doubtful attempts upon Hamas leaders has produced a stunning loss of civilian life, Israeli strategy supposes a territorially suffused guilt. Even the name Hamas functions substitutively in popular media, which prefers to speak of an “Israel-Hamas” war—at once repressing the actuality of Palestine and recasting civilians as foreign fighters. (Recall that, at the outset of atrocities, Israeli president Isaac Herzog stood before the world and claimed that “there are no innocent civilians in Gaza.”)

This isn’t only a rhetorical or political move. Rather, this conscription happens in the moment of deployment, as one becomes a target of a law-making-and-breaking artillery. With this order of operations in mind, it isn’t quite right to suggest that the drone is a weapon deployed onto a preexisting space of conflict; rather, as Nour Balosha notes to (Atef Abu) Saif, “the drone transforms Gaza into a field of war.” In the disclosure of target to drone, a zone of conflict is activated. If, instrumentally conceived, the will to kill ought to precede one’s choice of weapon, then the drone era flips the script. Today, a wilful inertia has infiltrated the technological means of combat, where rogue and warring states retain whole air-conditioned warehouses of “hunters,” scanning for plausibly pre-approved targets.

Just as Israel has innovated drone warfare from the technical side, it continues to advance its cause in the realm of legal apologia. On this, Saif quotes Colonel Daniel Reisner, former head of the International Law Department of the Israeli army: “International law progresses through violations. We invented the targeted assassination thesis and we had to push it.” This doctrine spans over 2,000 assassinations and seven decades of Israeli policy, though its shaky legality is consummated in the figure and era of the drone. And as the first state in the world to adopt an official policy of preemptive targeted killing, as well as an early workshop of drone technology, Israel appears the author of this moment, urging US policy in similar directions. In this respect, the killing of Arouri in Beirut only continues a longstanding project of imperial adventurism, as Israel defies its patrons to condemn their common framework.

Read the full piece at canadiandimension.com