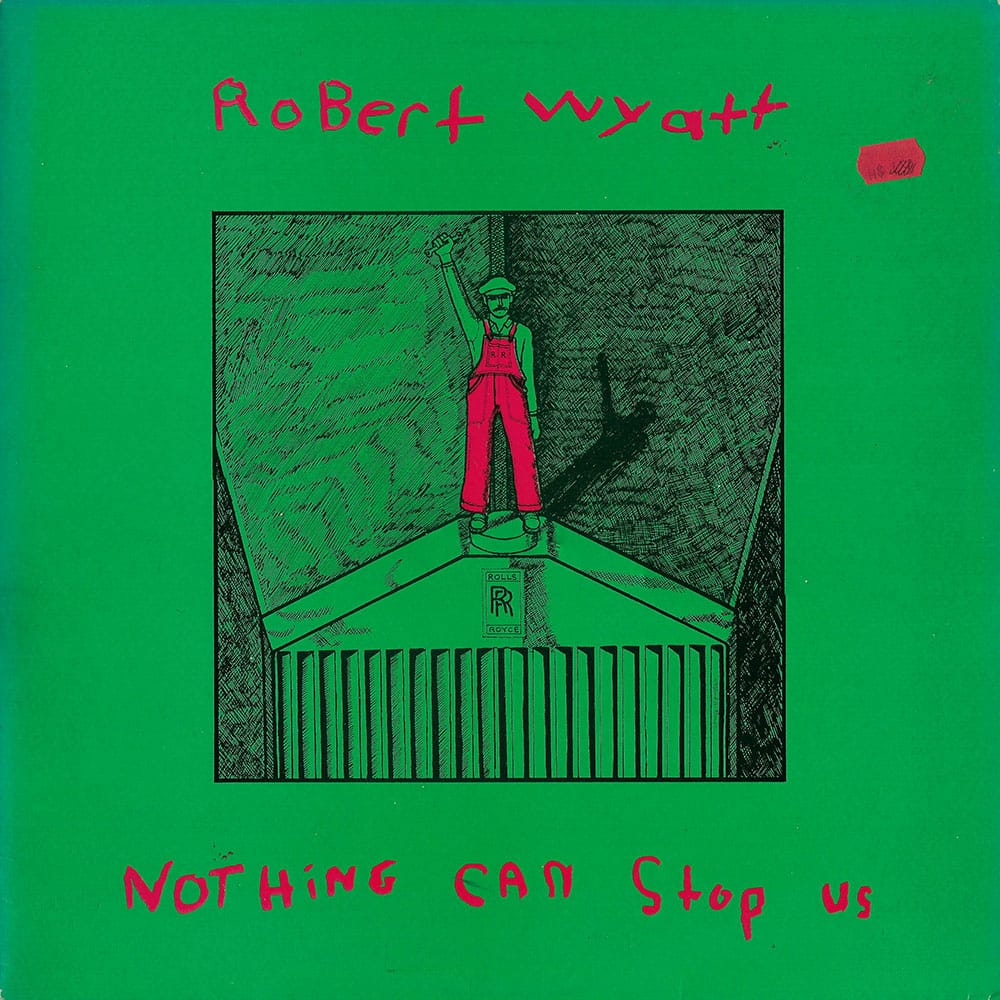

Nothing Can Stop Us

Robert Wyatt and Dishari Sing the Union

No May Day mixtape would be complete without at least several recordings by the one and only Robert Wyatt. From the labour carol of 'The Red Flag' to his deeply felt interpretations of Carlos Puebla, Wyatt's songbook is eclectic and convicted, and it feels good to ring in the occasion with Nothing Can Stop Us—a 1982 anthology of art-rock agitprop on which Wyatt lends his singular voice to all manner of popular canon.

Yet Wyatt himself doesn't appear on one of his most entrancing sides of this period. 'Trade Union,' released by Rough Trade in 1981, backs 'Grass,' an update of Ivor Cutler's 1975 song 'Go and Sit Upon the Grass.' It's a Punch and Judy show of a lyric, dryly intoned above a static drone; though Wyatt's version swaps Cutler's wheezy harmonium for the shehnai and tabla duo of Kadir Durvesh and Esmail Sheikh, as his multi-tracked vocal threatens the listener with common sense.

'Trade Union' develops this sonic palette, pitched percussion galloping atop a supporting drone, but without the direct participation of Wyatt, whose instigative role is more social than musical. Wyatt is only present as a recordist, while the music is performed by London-based Bangladeshi ensemble Dishari Shilpee Gosthi. As the liner note explains:

Dishari Shilpee Gosthi is a cultural organization formed in 1979, at the time when the racial tension in East End of London was very bad.

Dishari aims to propagate Bangladeshi culture, music, and literature amongst the host community in the UK; to create mutual respect and good understanding for each other's culture; to create the proper climate for good community relations by fostering brotherly feelings amongst the Bangladeshi youth and the younger generation of this country by cultural activities; to create and encourage harmonious society by multi-racial culture in this multi-racial society of ours.

This program assumes special significance at the time of recording. As Bangladeshi immigration to the UK increased throughout the 1970s, growing cultural enclaves such as Tower Hamlets in London's East End, residents endured an alarming spike in racist attacks from groups like the National Front, who terrorized the borough's thriving thoroughfare, Brick Lane; and from government policy as well, which abetted the street violence of neo-fascist formations from above, if tacitly. (The restrictive Immigration Act of 1971 came into effect during Bangladesh's War of Independence, and was clearly authored amid anxiety of heightened mobility within the Commonwealth.)

On May 4, 1978, textile worker Altab Ali was murdered on his walk home by a group of teenagers, spurring mass anti-racist action. Thousands of demonstrators took to the streets, led by groups such as the Bangladesh Youth Movement, and the National Front was effectively chased out of Brick Lane by months of rolling protests. As Kenneth Leech—an Anglican priest and activist in the Tower Hamlets Movement Against Racism and Fascism—describes, the local Trades Council was a key participant in this sequence too; co-publishing an investigation into prejudicial police tactics by the Brick Lane Defense Committee, and carefully tracking incidents of racially motivated violence in an independent report entitled Blood on the Streets. Against the backdrop of this anti-fascist organizing, the Tower Hamlets Trade Union Council (then named for Bethnal Green and Stepney) convened the Joint Trade Union Committee on Racialism, whose purposes, Leech explains, were several:

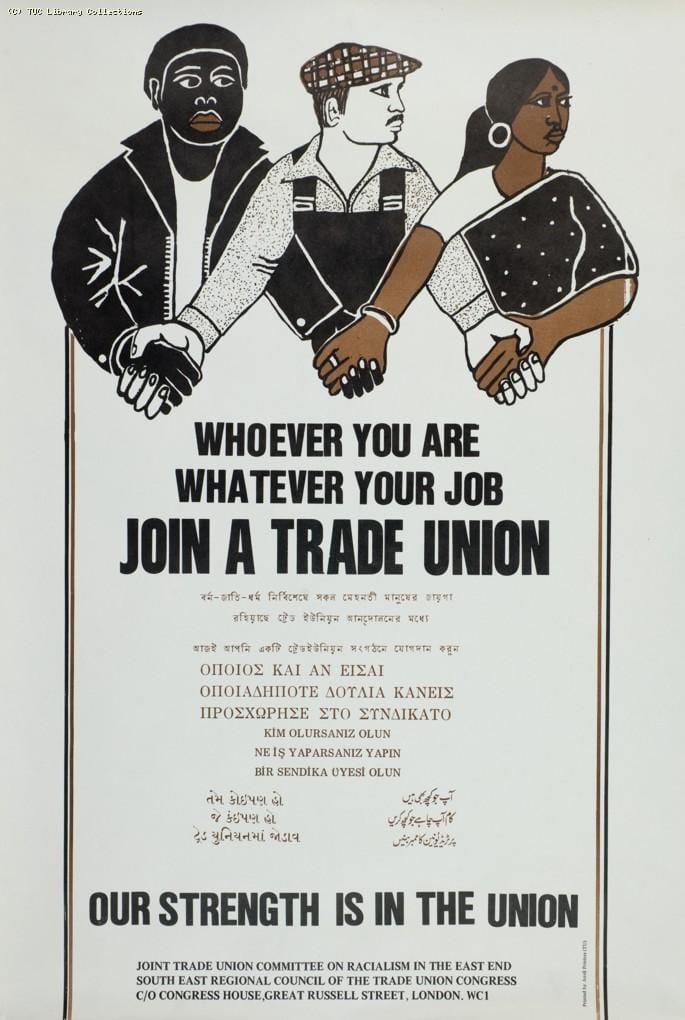

First, to secure effective Equal Opportunities Policies from all the major employers in the area, particularly in the public sector. Secondly, to encourage workers from the ethnic minorities to join appropriate trade unions through a massive recruitment drive, and to arrange training and otherwise help to enable them to play a full part in the movement. Thirdly, as a concerted effort to combat racialist ideas and practices where they exist within the unions.

This work transpired both door to door and at the factory gate, Leech says, but also entailed a good deal of artistic outreach; from a devoted film on unions made for Asian cinemas to the poster art and murals of artist and Trades Council organizer Dan Jones. Amid this organizational ferment, Dishari's side for Rough Trade sounds a rousing contribution to a multi-racial workers' movement against the far-right. As the liner note explains:

The present record, a trade union recruitment song, is recorded with the co-operation of Tower Hamlets Trade Council, by the Artists of Dishari and two famous guests Himungshu Goswami and Dulal Bhowmik, radio and TV artists of Bangladesh. Dishari expresses its gratitude for their co-operation. Dishari also expresses its gratitude to Robert Wyatt, an internationally famed artist, for his help and co-operation in recording this song.

But this modest caption only alludes to another moving context of the session and of Wyatt's interest, which doubled as an offer of practical employment. As Wyatt recounts, "there was this bunch of Bengali trade unionists who were being kicked out of Bangladesh and wanted asylum in England. The Home Office wanted to send them back. And I said, I know they make music, at their political meetings they get up and sing songs. So if we recorded them then we could say to the Home Office that they're working here. They're musicians, they're not just asylum seekers."

Surprisingly, according to Wyatt's biographer Marcus O'Dair, the ploy worked. Not only would the group continue to perform and organize in East London, but its bandleader Abdus Salique would go on to become chairman of the Brick Lane Traders' Association, in which office he continues to oppose the gentrification of the neighbourhood amid a flurry of media-driven redevelopment bids. Today his daughter Shapla Salique, who started singing with Dishari at the age of ten, is a renowned performer in her own right, bringing "Lalon to London."

Leaving aside its practical significance as a moment of international solidarity, 'Trade Union' is simply a stunning song; beginning with a languid evocation of hope in transit, and accelerating to an urgently persuasive repetition of the title—both a theme and a demand. As the song increases in tempo and density, independent voices converge, stating the need for organization in flurried unison. Salique's Bengali lyric is translated for the English-speaking listener, and speaks as urgently today as ever:

We were called from a distant land,

Counting the waves

Of thirteen rivers and seven seas,

With hopes of a better life.

We are the workers!

We labour in the factories and the workshops.

If we unite

We can grasp our rights in our hands.

Of course we must unite

If we want to defeat the racists,

If we want to draw the teeth

Of those who suck our blood and exploit us.

We must stand together

Under the trade union banner!

Trade union! Trade union!

Trade union! TRADE UNION!