Trench Confessions

A Seasonal Re-Reading of the First World War in Verse

Poetry has a special relationship to armed conflict. From The Iliad—“Homer’s epic of lousy war,” to quote Christopher Reid—through the bloody lyrics of contestant troubadours to the primal scene of modernism in the First World War, the technical advance of poetry seems to proceed in leaps and bounds alongside military conflagration.

Outside of the significance of language to nationcraft, one can imagine a social explanation for this accompaniment, where the poet’s brazen, gifted profile shadows youth’s conscription in matters of war. In retrospect, the useless negativity of the teenager, and its redeployment as a pure consumer function in the post-war period, plainly inherits a subjective profile innovated by the near-sacrificial mobilizations of the nineteen-tens, when youth becomes a job description.

The mass production of this identity might have awaited the aftermath of the world’s first imperialist war, but not without precedent. From the origins of romance in the crusading movement to the colonial bases of Rimbaud’s Illuminations, the poet has long been a kind of mercenary. This isn't the role of a propagandist per se, but of an obscurantist—attentive to national particularities, but not historical specificities; to intimate experience but not the conditions of its construction as such. Here too, poetry models ideology where it supposes a literary language that can bypass discourse and appeal symbolically to universal emotion.

Many ideological uses of literature explode out of the contradiction between the particularity of poetry to a national milieu and its proposed universality of address. But how does this transmission operate in a time of general enmity? How does poetry adapt to war?

Communities of Pain

Remembrance Day, observed on the anniversary of the Armistice of November 1918, is one of the few occasions still reserved for poetry on the national calendar. Verses are distributed to schoolchildren of all ages, by Laurence Binyon or John McCrae, whose undead chorus calls upon the living to “take up our quarrel with the foe,” and whose central image blooms upon lapels each fall. (For what it's worth, the conscientious mourner should don the white poppy, a symbol adopted in 1933 to commemorate all victims of war, including the civilian dead.)

Many present ideas about poetry and its public role descend from this era of European history, in which an effete, retreating art form once again fulfilled an urgent, popular task. From this emergency despecialization we receive the heavily romanticized figures of both the poet-soldier and the poet-journalist, whose firsthand attestation to the agony of history commends an elevated form—though not every act of literary witness is equally veracious, or even equally literary.

Compare the poetry of Wilhelm Klemm, a German field doctor, to the moral goading of a John McCrae. Devoid of patriotic fervor, Klemm’s lyrics evoke the stink of gangrene, of steaming viscera spilled over nationless earth:

There's a stench of blood, pus, shit and sweat.

Bandages ooze away underneath torn uniforms.

Clammy trembling hands and wasted faces.

Bodies stay propped up as their dying heads slump down.

There is no glory here, and the orderly, redeemed death of McCrae’s envisioning, sorted by rank in cemetery aisles, feels deceitful rather than ennobling next to Klemm’s works of eyewitness.

Importantly, Klemm’s blood-soaked countryside makes no distinction between the dead on the basis of their cause or origin—refuting Rupert Brooke’s boast that, should a British soldier die abroad, then "there’s some corner of a foreign field/that is for ever England.” In the trenches of Klemm’s verse, nobody goes to compost as a planted flag.

Klemm’s generalized disgust at war better resembles the slight literary output of Doctor Norman Bethune, whose 1939 prose poem ‘Wounds’ renders the mortal horror of a field surgery during the Chinese Revolution, but with clear-eyed political attribution. “In this community of pain, there are no enemies,” Bethune writes, placing his sights on the capitalist class that turns working men of different nations against one another: “Cut away that blood-stained uniform.”

Bethune writes from the midst of an altogether different war, in which it is possible to take a stand against the forces of imperialism by other means than desertion. As a result of this determinate stance, his redeployment of some standard tropes from the popular canon of “war poetry” takes a different meaning. In a lesser poem from the Spanish Civil War, Bethune appears to reverse McCrae’s undead entreaty to the living: “And to those nameless dead our vows renew/Comrades, who fought for freedom and the future world/Who died for us, we will remember you.”

Bethune's comradely epithet gathers the fallen in its address, summoned to living memory instead of a endless vendetta. In either case, it is the cause which confers a collective identity. McCrae’s ventriloquized dead speak as one of their quarrel with an unknown foe, but their fate as profit fodder in a senseless war is hardly enough in common to make a subject. Just who was “our” foe amid imperialist slaughter, in a war for conquest between emerging and "overgorged" powers?

Modern War

All told, the lasting legacies of the First World War in literature have more to do with the uses of war for poetry than with the use of poetry for war. The labyrinth of early modernism came to many dead-ends in this decade, each having uniquely to do with the purgative plans of a youthful—soon to be expendable—avant-garde.

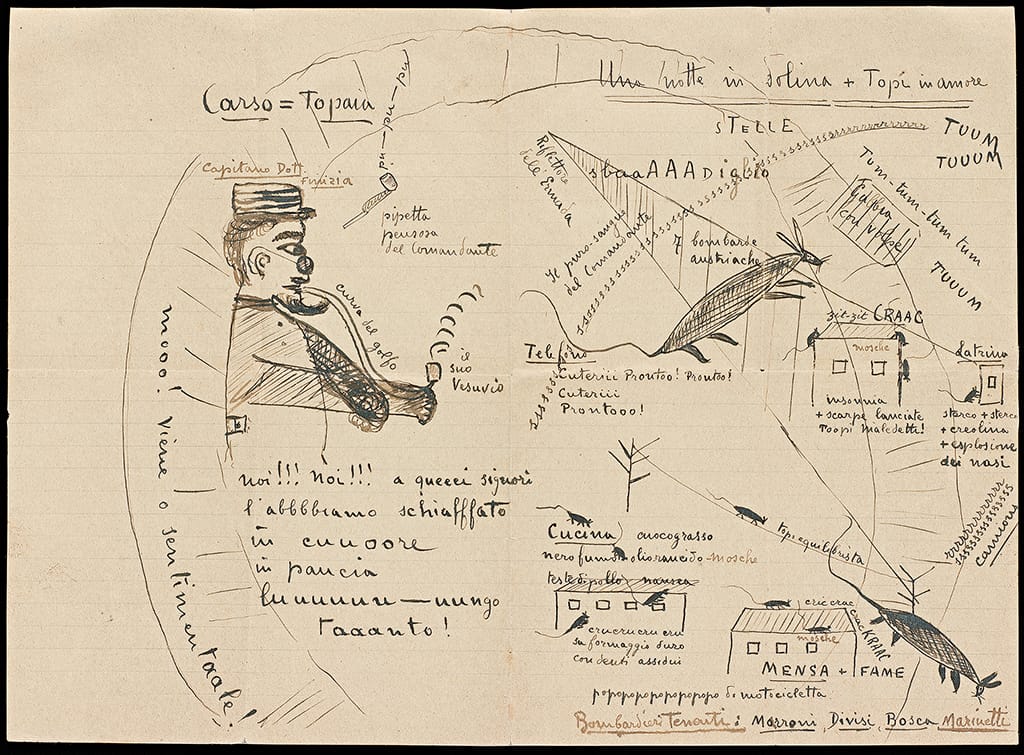

For Italy’s Futurists, an infantile obsession with technological transgression, backed by a crudely taxonomized description of European decline along racial lines, obliged a once-aesthetic provocation to an explicitly interventionist stance. With characteristic haste, F.T. Marinetti’s brash artistic manifestoes sprouted an ultra-nationalist political party, destined to merge with the Fascists at the close of the war; and before long, the irreligious, anti-bourgeois provocation of his early program was foreclosed to socialist interpretation once and for all.

By 1916, Marinetti’s master metaphor—of war as a sloughing off of history and national inertia—had turned to active propaganda for imperialist slaughter. Of course the break is hardly so abrupt: Marinetti’s “pan-Italian’ irrendentism was first stated at the colonization of Libya, and his racism simply extends the values of Gabriele D'Annunzio and the Nietzschean company that raised him. If anything, an earlier conviction in the cleansing power of war only deepened during combat. This was the purge that Futurism had predicted, and where accomplices like Carrà flinched, Marinetti fluorished.

Futurism’s Russian counterparts were shaken as well, in spite of their total repudiation of Marinetti’s example and the absorption of key figures in the early energies of Bolshevism. Even the revolutionary Mayakovsky vacillated in the face of war. "At first took it only from the decorative, jingoistic angle," he admits in his terse, essential memoir, I Myself. Weeks later: "The first battle. The horror of war in all its stature. War is disgusting. The rear is even more disgusting. To talk about war, one must see it."

The visionary Velimir Khlebnikov viewed continental war as the inevitable outcome of the archaic rule of space, soon to be superseded by a government of poets who would rather preside over time. This is an obscure proposition, more sophisticated than the Italian call to "yield up to youth all rights and all authority." But despite their revolutionary verve, Khlebnikov's wartime classics make a more or less science-fictional response to contemporary conditions.

In a 1916 text, 'The Trumpet of the Martians,' Khlebnikov describes the conquest of time as an abrupt generational succession, defying the sedentary ethnocentrism of the family unit and inaugurating a state of industrial momentum and youthful innovation. This neophiliac program opposed the hated and decrepit Tsarist “getters” (as opposed to proletarian "begetters" of all wealth and resource; elsewhere this pair is translated as exploiters/explorers or investors/inventors) and announced a total separation of generations. But even a precocious "Martian" poet could not escape the draft, and Khlebnikov would spend the rest of his life reeling from the trauma of space.

As Never Before

Elsewhere, the Great English Vortex was effectively reversed by the extent of the war, and the senseless martyrdom of its youngest and brightest expositor. The sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska was regarded by both Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis as the best in their midst, a natural whose eye to organic form could bypass cultural and linguistic barriers. (Pound took this claim to extremes in his fetishization of the Chinese written character, claiming that Gaudier-Brzeska could read pictographs from intuition alone.)

In the second and final issue of BLAST, the movement's flagship, Gaudier-Brzeska wrote from the trenches: “I HAVE BEEN FIGHTING FOR TWO MONTHS and I can now gauge the intensity of life. HUMAN MASSES teem and move, are destroyed and crop up again. HORSES are worn out in three weeks, die by the roadside.” This transcription rivals the gored landscapes of expressionists like Klemm or Trakl, but with enthusiasm for the scene. For Gaudier-Brzeska, war refutes artistic feeling, as pure form reveals itself beneath each fleeting conflict:

WITH ALL THE DESTRUCTION that works around us NOTHING IS CHANGED, EVEN SUPERFICIALLY. LIFE IS THE SAME STRENGTH, THE MOVING AGENT THAT PERMITS THE SMALL INDIVIDUAL TO ASSERT HIMSELF.

THE. BURSTING SHELLS, the volleys, wire entanglements, projectors, motors, the chaos of battle DO NOT ALTER IN THE LEAST the outlines of the hill we are besieging.

For all its naive enthusiasms, Gaudier-Brzeska’s text strongly distinguishes itself from Futurism’s technical effusions. One could contrast Marinetti's writings from Trentino, in which he finds the hulkingly indifferent Dolomites to have been redeemed at last by war. Rivers are activated as an aid to logistics; mountain ranges “reacquire the essence of their soul” as an aid to artillery. In this account, none of the region's features please the militarized intellect until they resonate with Marinetti's racial and cultural vendettas.

In a real sense, Gaudier-Brzeska’s dispatch would become the final manifesto of the BLAST group, shouted orthography dissimulating doubt. (Family letters make an ennervated, fearful contrast: "Life is very monotonous and animal, one hasn't the energy nor the desire to think, and one is too disturbed to concentrate anyhow.") Gaudier-Brzeska died in combat shortly after having his theory of sculpture corroborated by the sloping trenches, and his senseless death would summarize a decade for his peers.

In his memoir of Gaudier-Brzeska, Pound decried the “lycanthropy” of nations through the war-surge, though his interpretation of events would soon unfurl one of the most errorful attempts on history ever committed to verse. In the meantime, his ‘Hugh Selwyn Mauberley’ draws a sharp line across the output of an era:

Daring as never before, wastage as never before.

Young blood and high blood,

Fair cheeks, and fine bodies;

fortitude as never before

frankness as never before,

disillusions as never told in the old days,

hysterias, trench confessions,

laughter out of dead bellies.

‘Mauberley’ combats the maudlin, jingoistic lyricism of War Poetry in its design, as well as the drawing room airs and weak aestheticism of Pound’s prior company. This double-edged critique still cuts today, where poetry's cult of death is partly sustained by preciosity and cool remoteness. But in context of the decade's literary output, most of which Pound opposed, its appeal lies in a rare, palpable rage.

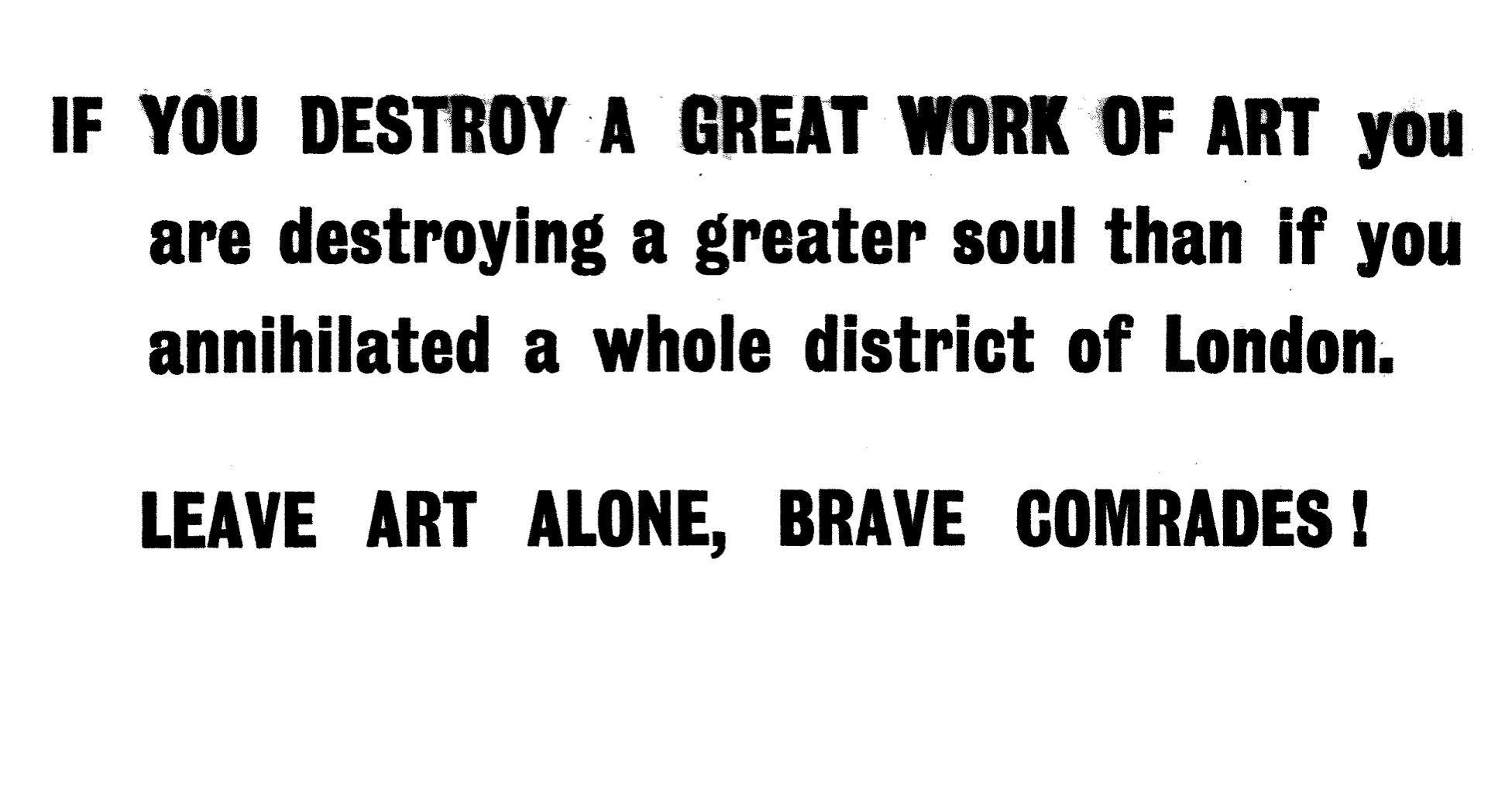

In the later 'Canto XVI,' Pound inventories the war experience of friends and colleagues, each of whom lives or dies as an ouevre. This is a polyvalent text, and its hellish scenery is densely populated. But the litany of proper nouns by which Pound grapples with the war's enormity offers more than a who's who of a bygone era. Past a point, Pound can no longer reconcile his theory of the artist as a gifted historical complex with a typically modernist itinerary of volitional destruction. "IF YOU DESTROY A GREAT WORK OF ART you are destroying a greater soul than if you annihilated a whole district of London," Lewis had written in the pre-war issue of BLAST, and Pound restates this mortal rate of exchange in his eulogy to Gaudier-Brzeska, whose "own genius was worth more than dead buildings."

A Poet in the Universal Army

In this respect, Pound's anti-war polemic also rallies to the figure of the soldier-poet—not as an eyewitness or dispatchable laureate, but as a civilizational metonym. This too is obscurantist, where it fails to condemn war in the everyday; war from the air; and war as a non-aristocratic concern. Before the war, Pound was a self-fancying troubadour whose many personae included that of the Medieval warlord, and for whom battle was a test not just of mettle but of type. (More than a decade on, he adds a doleful footnote to one of his bloodier translations of Bertran de Born: "This kind of thing was much more impressive before 1914 than it has been since 1920.")

In the masculinist understanding of early modernism, the mercenary and the poet were complementary figures; not because of any representative relation to the masses, but as operators of pure will. For Marinetti, the new intellectual is "ruled only by a divine, intoxicating intuition," and is "ablaze with the proverbial sacred flame." However distinct their artistic itineraries, this isn't so unlike Pound's idealization of the artist as an apprehending vortex—and he appears to discover the horror of war where it begins to threaten his ideal type, thus civilization in miniature.

This voluntaristic conception of greatness is inverted in the figure of the soldier-poet, whose moral authority and universal bearing follow from historical compulsion, not a self-originating will to power. The soldier-poet doesn't author history, but endures the decisions of their superiors—not as a wayward genius or a fragment of higher society, but as an everyman or reluctant witness.

As a popular figure of contrary specializations, the soldier-poet appears only when war has come to totally suffuse society and every conceivable role therein, collapsing ever more remote divisions of intellectual and manual labour. As such, this role is utterly distinct from the military genius or poet-baron of preceding centuries, and can be seen as a subjective innovation of the imperialist epoch.

Naturally, the swelling of a standing army implies the presence of poets and other traditionally petty bourgeois occupations at the front, though the class composition of these ranks changed perceptibly at key moments throughout the war. Millions, not thousands, served, and while conscription was mostly introduced in order to repopulate the devastated fronts, young men flocked to enlist from many classes and levels of education. Poetry was immanent to this totally mobilized society, as were any number of other specialties less apt to propaganda.

But the true poetry of the fronts opened a window onto scenes of barbarity without redemption. As a brutal war of attrition drew stock from an urban civilian reserve, the contest between journalistic and jingoistic representations of slaughter assumed greater significance. Even so, critical representations of the war were rarely couched in a language of dissent. Despair predominates on all sides, though each country's poets would relay this affect to their own in different ways.

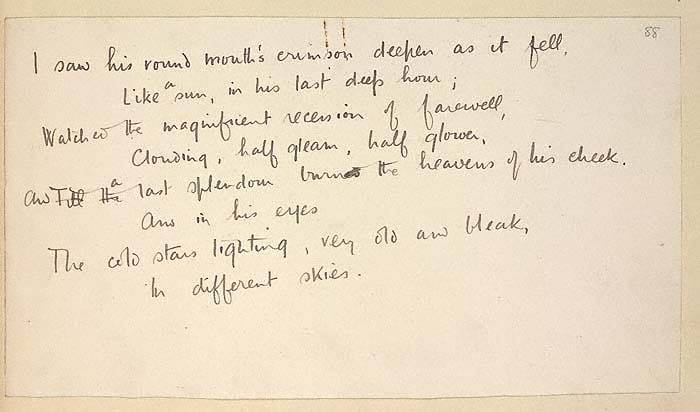

As urgently, the time of reception changes the resistant quality of war poetry, regardless of its political intent. Front poets like Wilhelm Klemm or Wilfred Owen each jammed national codes in their unflinching depiction of the war's toll, but their respective paths to publication couldn't have been more different. Klemm's verse appeared in the magazine Die Aktion, a banner publication of the shortlived Antinational Socialist Party, where writing from the front was presented with the explicit intent of opposing the war. This is a rare trajectory, where the English language reputation of soldier poetry as principally revulsed and pacifistic was a compensatory, post-war construction. Owen, poet of England's guilty conscience, hardly published in his time, and joined the ranks of those doomed youth "who die as cattle" only days before the Armistice.

The larger part of British wartime verse was given over to imperialist pablum, underwritten by the secretive War Propaganda Bureau. (A 1914 conference at Wellington House included luminaries such as G.K. Chesterton and Thomas Hardy in its scheming.) Owen's original draft of 'Dulce et Decorum Est' was dedicated bitterly to Jessie Pope, whose Home Front exhortations are all but forgotten; but her brand of bloody doggerel was little opposed in its day, and the moral clarity and sober witnessing associated with the Great War poets was largely established by anthologists in years to come.

Our Quarrel

This hasty syllabus already spans far more text and politics than could be reasonably assigned come November. So where does this leave us today? It would be strange to claim that poetry remains a means of war when its cultural niche is so diminished. If anything, its present profile tends to pacifistic certainties and to social abstention, which poses its own challenges. But once a year, our national pride flares at the memory of war, and the story we receive rhymes tidily.

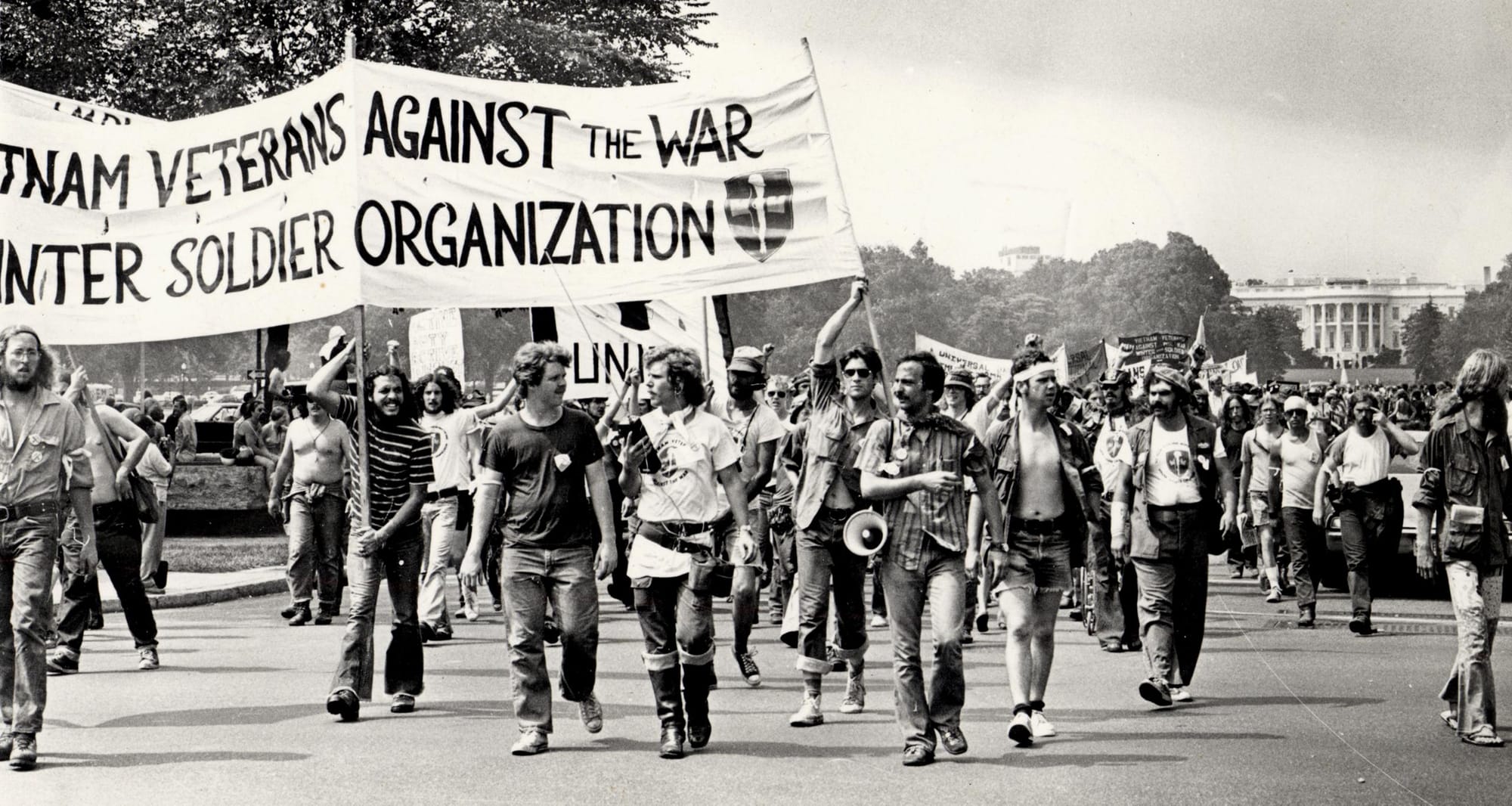

Poetry has been a live chronicle of conflict, but as its social meaning changes and this recollective task becomes one of commemoration instead, we need to make new anthologies of past experience. For a variety of reasons, the World Wars may have been the last time at which a volunteer army in the west could produce literature at all. The soldier-poet was a direct outcome of the socialization of a capitalist war, while contemporary combat tends to remote specialization and targeted recruitment—partly in order to prevent such internal dissent.

Writing only names a larger problem here, and one can think of other media by which we have been called to witness the atrocities of a century, from the photojournalism of the Spanish Civil War to the resistant musics that scored and corresponded with the draft-based invasion of Vietnam. (A separate essay could take up the poetry of Gaza, which encompasses the first-hand witness of medics and journalists.) But as popular participation wanes and imperialism places an ever wider gulf between parties to conflict, the cultural expression of aggressor nations holds little interest or moral authority.

In today's tributes, the archaic figure of the soldier-poet often features to collapse this distance, as if imperialism could furnish itself a moral chorus or disinterested witness in the course of its crimes. There are countless reasons why this is no longer the case, but the era of literature from which our ruling class prefers to quote is far more varied and revealing than fall ritual admits.

Partial remembrance is still a type of forgetting, and no credible ceremony of peace should fail to apprehend the cause of war. As we see annually, poetry can play its part in this comprehension, so long as we read across national lines and widely—lest we forget those cultures of dissent against assigned death, and of revolutionary fervor in the depth of global crisis.

As for the barracks poetry we learn by rote, rhymed lies lack beauty. And although poetry is hardly read today, there may be a reason why the artless politicians who exchange the living for their own advantage have retained a taste for metaphor.

But they are troops who fade, not flowers,

For poets’ tearful fooling:

Men, gaps for filling:

Losses, who might have fought

Longer; but no one bothers.