Who's Afraid of FEAR?

Let's have a war!

Jack up the Dow Jones!

Let's have a war!

It can start in New Jersey!

Let's have a war!

Blame it on the middle-class!

Let's have a war!

We're like rats in a cage!

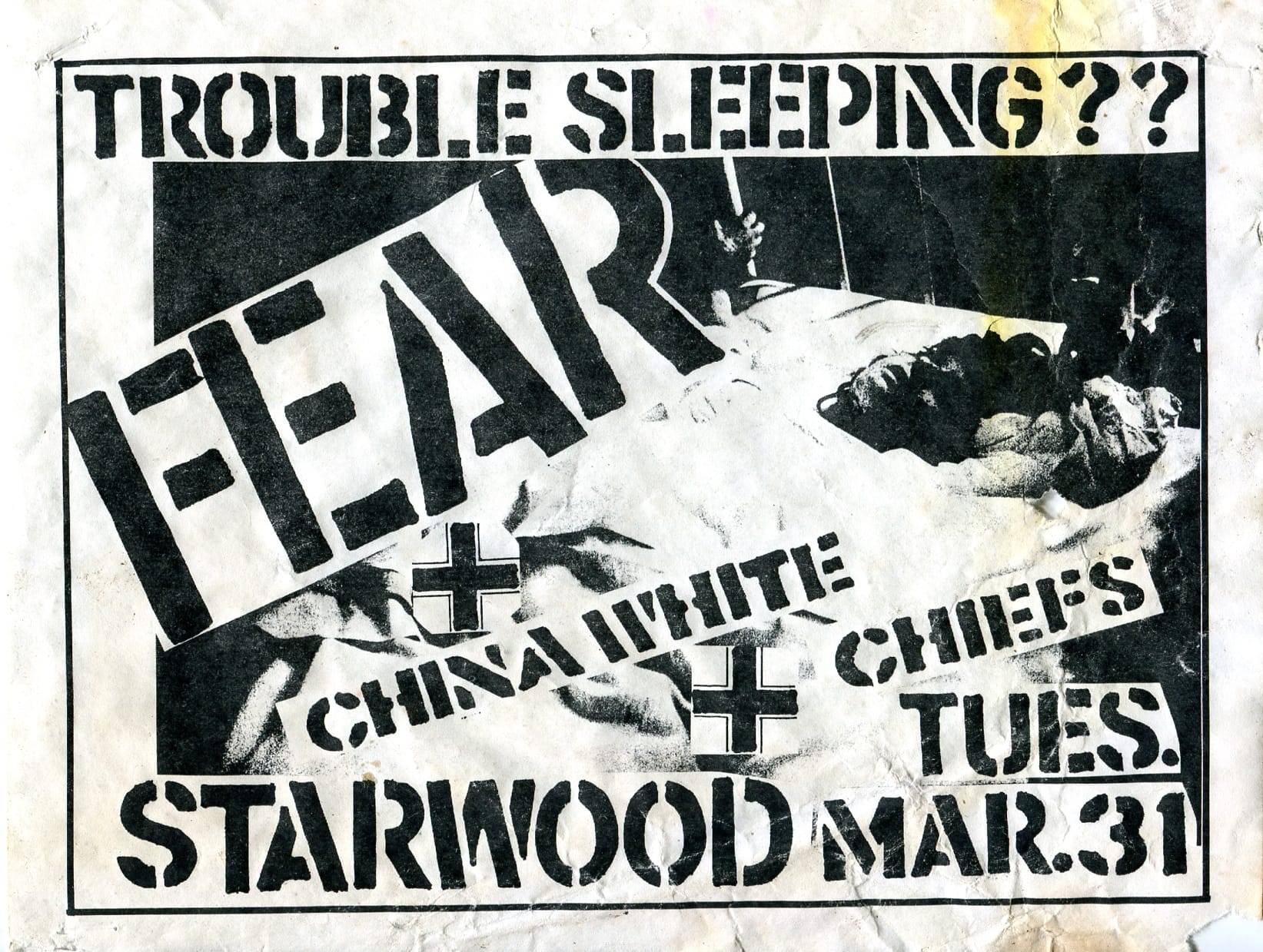

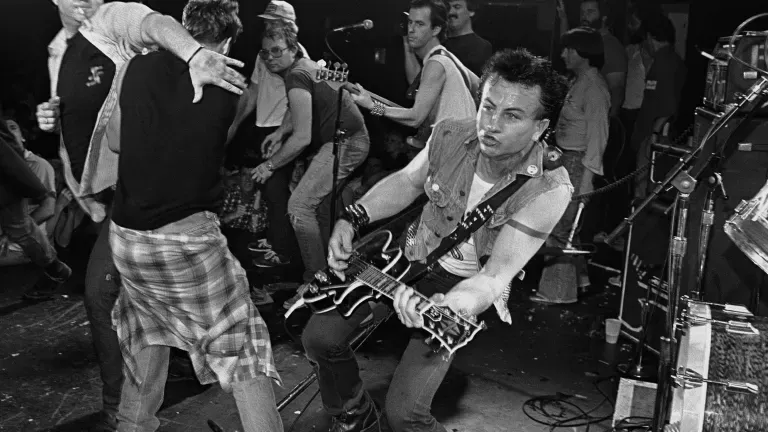

Last weekend, as the world teetered on the brink of war and Minneapolis took to the streets against ICE, my punk band played a show with FEAR. Yes, that FEAR, of celluloid posterity and hardcore legend. (Are we to capitalize every occurrence?) This isn't much of a coincidence in itself: America is always stoking armageddon, and Lee Ving has to play somewhere on a Friday night. But every time we leave the house we ought to ask ourselves how we should like to spend our last plausible moments on earth.

FEAR are one of the great US punk bands, and far weirder than one might initially recall. Lee and co. were the toughest outfit of a various era, but the bullying offensive of their first album works because of its progressive inklings. 'New York's Alright' is a masterpiece of performative contradiction by a band steeped in jazz and the city, and the industrial persistence of 'We Destroy the Family' makes the most intense records on SST or Touch and Go sound sluggish by comparison, as if played at the wrong speed.

Truly, FEAR's sharp angles and odd time signatures presage the best of noise rock sooner than the plodding pub punk that they would inspire. This error of translation can be chalked up to diminishing returns on punk's initial flash of inspiration, which trends generic (even gloriously so)—but that doesn't really get at the ideological complement of this musical degeneration.

Clearly FEAR's right-wing politics are a performance, and Lee Ving plays a character throughout their wildly uneven songbook. In this respect, he isn't so different from a Jello Biafra or a Dave Insurgent, whose provocations are exclusively intelligible in anti-fascist registers. By daring the listener to relate directly to the worst conceivable outcomes of Cold War politics—up to and including atomic death—FEAR give the lie to Reagan's "shining city" from within the ranks of his domestic base.

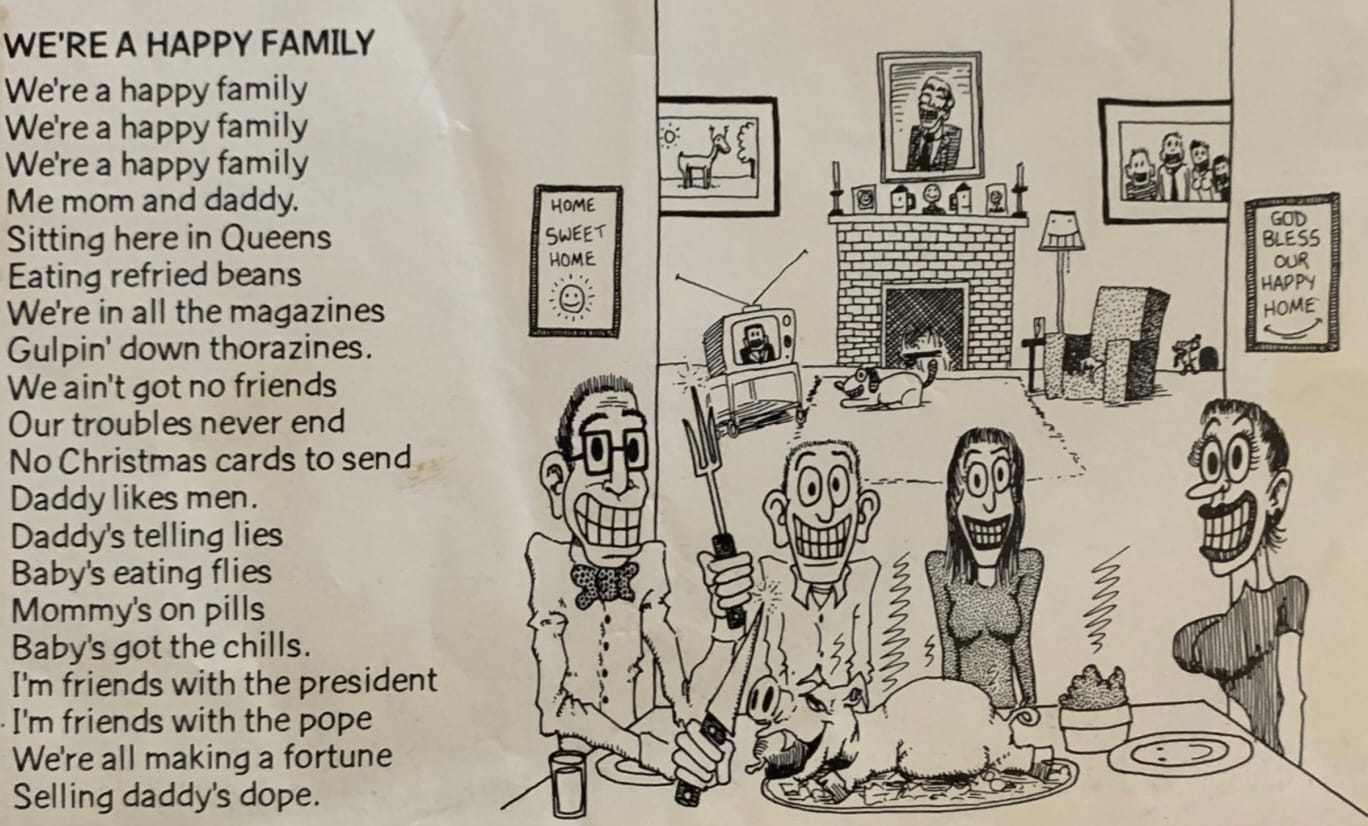

At the same time, Lee's humour feels more closely related to that of our begetters, the Ramones; who are very funny but as deeply conservative. From unprompted anti-Russian animus to ironic depictions of the family firm, FEAR take the pet themes of the Ramones to antagonistic extremes. Unlike Joey, however, Lee is not the pinhead subject of lobotomy and solvent abuse, but the Doctor and Primal Father at once. This enunciative difference may even correspond to a cultural shift between punk and hardcore, where the latter tends to the affectation of power and autonomy; but that's another argument. Suffice it to say that regardless of intent, these bands are such pure products of America that even their stated values sound like satire.

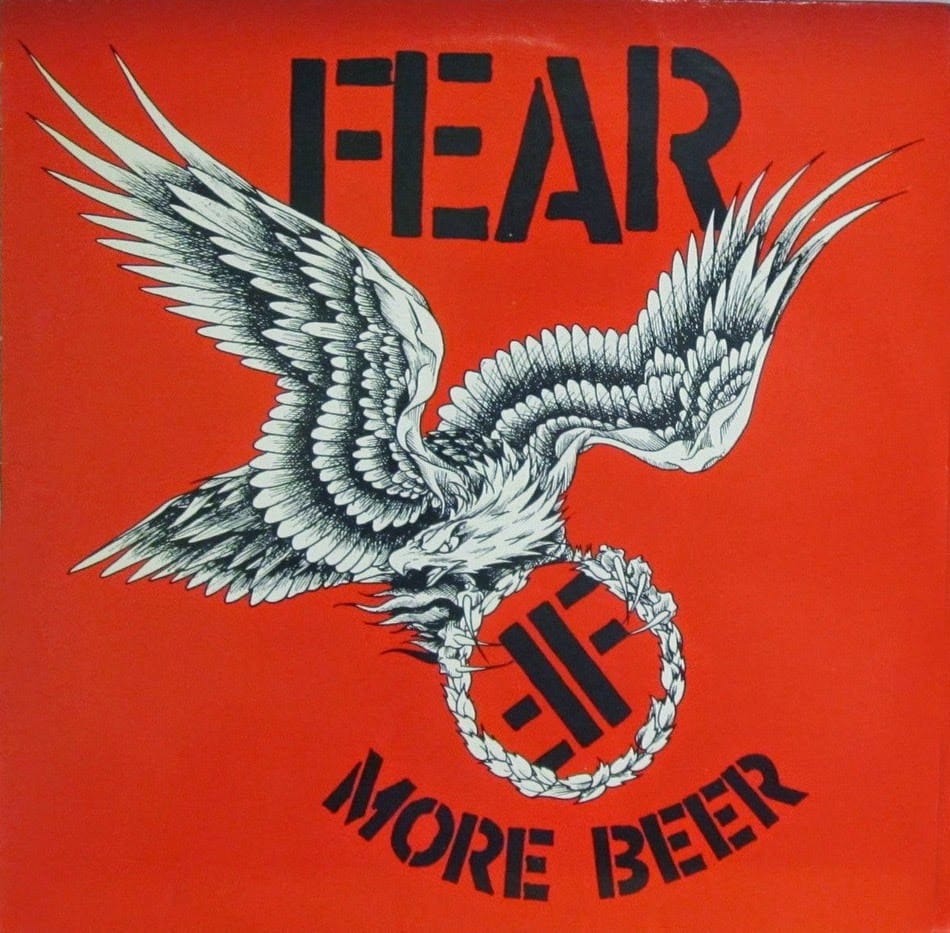

FEAR succumbs to self-referential schtickiness by their second album, More Beer, best known for its look-twice, crypto-fascist cover art. This more or less completes their reputation; and pandering or not, the music sheds its dissonance and comes to resemble anthemic bar rock in this era too. It's a charmless set compared to the first album, with some admitted hits and lots of swagger; but punk was in an odd state in the mid-eighties, by which time most of the bands anthologized by Penelope Spheeris in The Decline of Western Civilization had veered into hard rock, and to varying results. (The lecherous sludge metal of Black Flag's Loose Nut, for example, retains its musical and satirical edge; while X's would-be breakthrough, Ain't Love Grand, suffers audibly from the involvement of hair-metal magus Michael Wagener.)

FEAR fares alright in this era, having subordinated their Blueshammer chops to a more spartan aesthetic at the outset of the hardcore movement. Unfortunately their major concession to heavy metal attitude is ideological, as the ironic counter-positioning of their early output gives way to drunk punk cliché and unreconstructed sexism. Where FEAR: The Record made a semiotic minefield of its rougher material, More Beer simply jeers.

The problem with this kind of Punk Shit isn't literalism per se, where fans and critics are equally likely to mistake the point. Rather, its social and interpretive difficulties tend to arise on the barricades of what used to be called "political correctness"—in the encounter between the artless literalism of outside detractors and the equal credulity of punk's participants, who in their silos come to think that any behaviour whatsoever is effectively licensed by its opposition.

At their most eloquent, FEAR is a mirror, filtering Cold War paranoia and post-Vietnam traumatic stress through a derelicted urban trench—the musical corollary of Taxi Driver in film, misogyny and all. Properly considered, the truthfulness of this historical disclosure has nothing to do with the subjective attitude of the singer toward his materials. FEAR is a symptomatic text, which asks the audience—scolding or emboldened—to countenance their own desire. (You talkin' to me?)

So what does FEAR want? Evidently, 'Lee Ving' relates to all signs of civil decline with interest rather than concern; and his laughter sounds beyond denial and endorsement. Lee's songs profess affinity with those nihilizing processes that mock at and threaten passive enjoyment—from wars for profit to the disintegration of public safety. FEAR's vision of total conscription in imperialist war ("Give guns to the queers!") extends and doesn't contradict their recommendation of Mansonian violence at home ("Fuck the government! Kill the home owners!"), correctly apprehending the relation between US Foreign Policy and domestic terror.

This is something that perennial debates as to the viability of "Conservative punk" often get wrong, as well-meaning participants try to map a conventional left-right spectralization of politics onto the music's pro- and anti-social flanks. This simply doesn't work, where punk's vague negativity recommends a strictly offensive posture whatever its content. FEAR is nominally right-wing, but hardly conservationist—rather pledging to destroy every typical retreat of the so-called moral majority. But without some inventory of the normative values that one might wish to expand or defend, it's difficult to contrast political itineraries. In any case, it's obviously untrue that punk rock obliges leftist or progressive values. If anything such instances, from the Clash to the Dicks to Bikini Kill to Born Against, have been embattled and emerged from local opposition.

But FEAR isn't Agnostic Front or Warzone, for example, who still profess the first-person earnestness of a sainted frontman like Ian MacKaye, but with a lumpish, patriotic input for a conscience. (Both bands, incidentally, are great.) FEAR are lustful, leering, evil; also cute, cartoonish, winking and nudging throughout the performance. In this respect, we should remember that punk politics mostly amounts to a scene-on-scene gimmick match with very little real world pertinence. FEAR's (mostly quaint) provocations are at no risk of being taken seriously; and where they do retain an air of threat, it's less to do with the songs themselves than the permissions they extend, and the mood in the room.

The whole point of punk's shock rock imposture is to make a re-initiation rite of every show and record, and I'm well aware that even trying to parse this topic places me outside the group formation that such signs coordinate. But everybody has their different limits, past which the pleasure of transgression starts to sting and something in one's own experience forbids kidding around. Offence is just this particular, and one of the most tellingly parochial errors of punk provocateurs is to treat the giving of offence as a method of universalism in itself: "nothing is sacred"; "I hate everybody equally"; and so on, tiresomely.

It's a somewhat restless feeling to be watching FEAR as the world warms to near-war on several fronts, including the streets of the United States. "Think the end is near? That's why we're here," Lee bellowed in a malt-themed mini-set, recusing the crowd from concern. But gonzo rituals assume a certain sweetness under stress, and I had a surprisingly good time with a classic band last Friday. As for punk's enduring power to convoke a roomful of seeming adversaries, that's a matter for another (rapidly approaching) day.

Beginning with FEAR, listen to an hour of raging hardcore punk on last Monday's episode of Radio State: every Monday night!